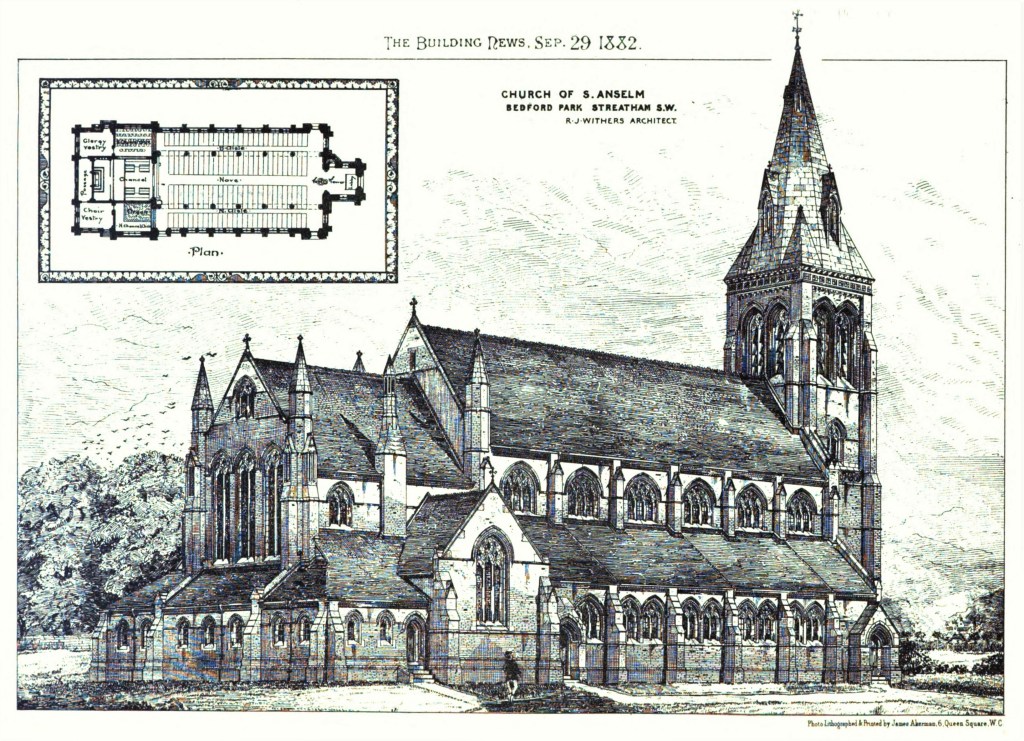

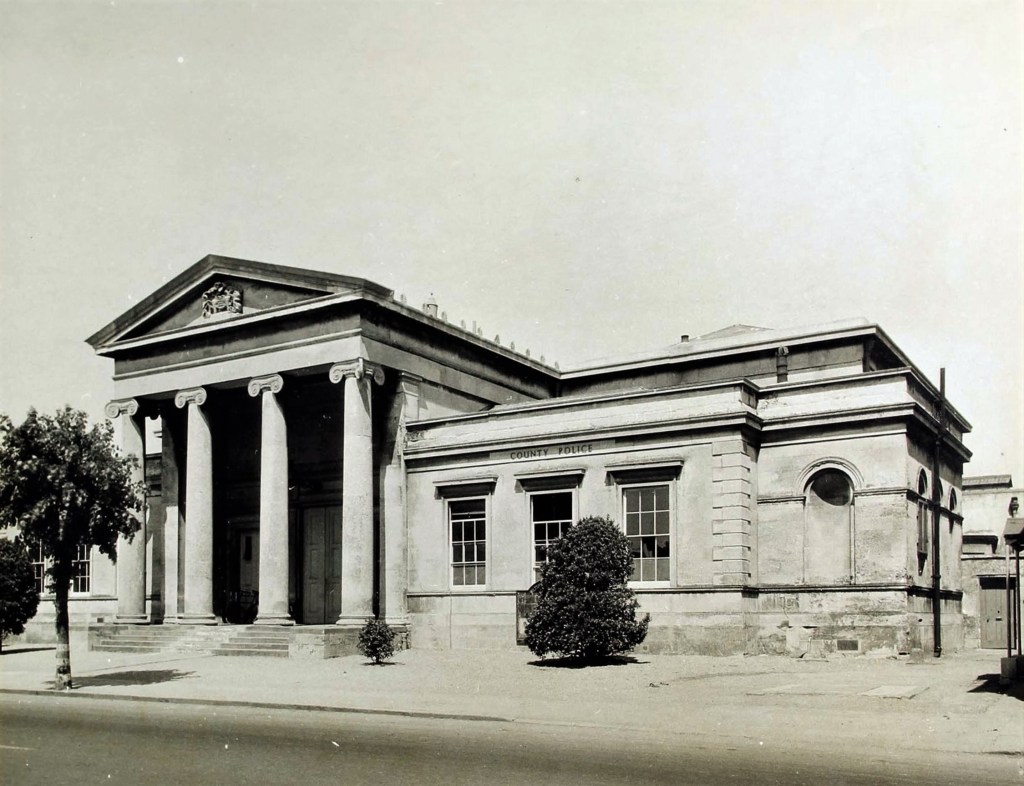

Several of the architects featured so far in this blog were, for all the distinctiveness of their architecture, specialists in a particular building type, be it churches, country houses or non-conformist chapels. Where 19th century architects were professionally more omnivorous, they tended to cut their stylistic cloth according to the commission. Though we think of ‘Gothic’ as being synonymous with ‘Victorian’, in fact the style was very far from ubiquitous, especially in the first half of the 19th century. Thus it is that Wyatt and Brandon, though usually Goths for ecclesiastical purposes, could pull out of the hat a piece of Greek Revival delivered with total conviction for the Shire Hall in Brecon.

But in this post, I want to look at architects who in many ways are the inverse of that – the joint practice of John Wilkes Poundley (1807-1872) and David Walker (18??-c. 1892). They employed consistently a style that bears such a strongly personal stamp and there is never any mistaking it – get your eye in with two or three of their designs and it’s very easy to recognise anything else by the firm, whatever the function of the building in front of you. They were prolific and this post does not pretend to be an exhaustive survey of their output. Rather, the aim is to show through a selection of works, presented here chronologically, just how deft they were in adapting their style to a wide variety of building types.

First, some biographical details, for which I am indebted to J.D.K. Lloyd’s brief but informative article ‘John Wilkes Poundley: A Montgomeryshire Architect’, which originally appeared back in 1977 in issue No 65 of Montgomeryshire Collections. It is, as far as I am currently aware, the only study in print devoted solely to the architect’s life and work. Poundley was a native of Kerry, a village about three miles to the west of Newtown in Montgomeryshire (now Powys). His grandfather, also called John Poundley (1744-1825), had been a schoolmaster in the village of Lydbury North in Shropshire, not far away over the English border. In 1763, Clive of India purchased the Walcot Hall estate in that parish and commissioned Sir William Chambers (1722-1796) to remodel the existing house. Around that time, he appointed Poundley as tutor to his young son Edward (1754-1839). The connection is important as it brought Poundley into the orbit of landed families in the area and this had a major bearing on his grandson’s choice of profession.

Poundley’s father, also called John, ran a small academy in Montgomery, but died young in March 1811. His widow passed away nine months later and their only son, aged just four at the time, passed into the guardianship of William Pugh (1748-1823), a lawyer and banker from an old landed county family, who resided on the estate of Brynllywarch in the parish of Kerry. In 1827, Pugh had the young J.W. Poundley apprenticed to Thomas Penson of Oswestry (1790-1859), architect and county surveyor of Montgomeryshire and Denbighshire.

A promising start, one might imagine, but according to family tradition (when carrying out research for his article, Lloyd was able to interview the architect’s last surviving descendant), Poundley disliked working in Penson’s office so intensely that he ran away to Dublin. What happened next is not clear and he does not re-emerge until the mid-1850s, by which point he had set up in partnership with David Walker (18??-c.1892) in a practice engaged in architecture and surveying. Walker had trained in the offices of a Liverpool firm run by John Hay (1811-1861) in partnership with his younger brothers, William Hardie Hay (1813/14-1901) and James Murdoch Hay (1823/24-1915), which was in business from c. 1848 to 1901. The Hays handled a large number of ecclesiastical commissions throughout the country and for all denominations, generally designing in Gothic of a decidedly wilful character. Walker remained in Liverpool and the business address of the partnership was on Lord Street in that city, but Poundley seems to have been based in Kerry, where he resided at Black Hall, and it is not currently clear how commissions were divided up between the two men. Neither ever became a member of the RIBA.

At some point during this period, Poundley came into contact with the Naylor family, which also had prominent land holdings in the area. John Naylor (1813-1889) was heir to a business empire founded by his great-uncle Thomas Leyland (?1752-1827), merchant and three-time mayor of Liverpool, who had amassed a fortune through international trade and slaving. Following abolition in 1807, Leyland had gone into finance and set up a partnership with his nephew, Richard Bullin, which became the highly lucrative concern of Leyland and Bullin’s Bank. In 1835, Richard Bullin (who later took the surname Leyland) had acquired the Brynllywarch estate at Kerry from William Pugh’s son, William Pugh the younger (1783-1842). This Pugh was a magistrate and entrepreneur who, among other things, actively supported the extension of the Montgomeryshire canal to Newtown in 1815-1819, the macadamizing of the county’s turnpike roads and provision of more direct access to South Wales via Newtown and Builth. But none of these ventures or any of his investments proved successful, forcing him to sell up. Then in 1845, Bullin purchased the 4,000-acre Leighton Hall estate just outside Welshpool to the southeast and gave it to John Naylor as a present to mark his wedding to Georgiana Edwards, following it two years later with a gift of £100,000.

Naylor quickly embarked on an ambitious building programme. In 1850, he began remodelling the existing house and gardens to reflect his wealth and status. The project was conceived on a grandiose scale and work went on until 1856. The finished result sports a tall octagonal tower redolent of Beckford’s Fonthill Abbey, and indeed externally the design was still largely Georgian Gothick in spirit. In 1851-1853, he put up a new church dedicated to the Holy Trinity, a scaled-down cathedral with flying buttresses to support the nave, an octagonal burial chapel like a chapter house and a tall spire visible for miles around. For both of these commissions Naylor engaged the obscure Liverpool architect of William Henry Gee (dates unknown). But his interest in building went a long way beyond trophy projects, and before he had even begun work on the new Hall and church, he embarked on a major programme of reconstructing the estate buildings.

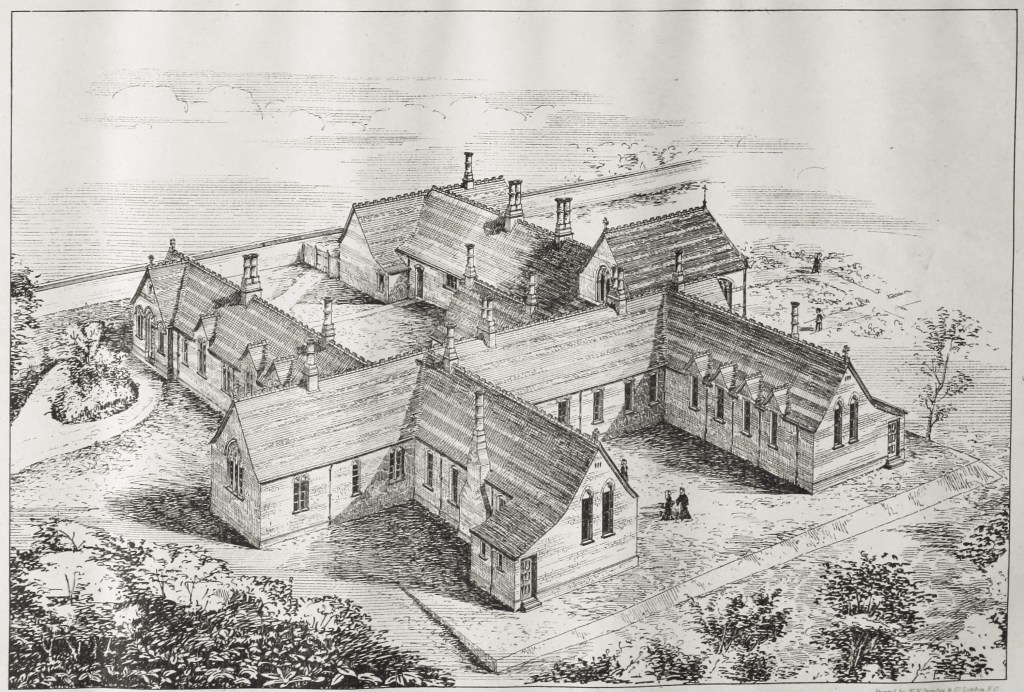

As a member of the Royal Agricultural Society from 1849, Naylor had an active interest in agricultural improvements and he was evidently keen to make Leighton Hall a showcase for them. Around that time, he began work on a new complex for the Home Farm, located to the north of the Hall about half way between it and the church. It was a major undertaking, and not completed until the early 1860s. The centrepiece, constructed in the first phase, was a large threshing barn, arranged on an east-west axis and adjoined by a granary and hay barn, with an adjacent, basilica-like fodder building. In the second phase, a stable with a central loading bay appeared at the south end of the main complex, along with enclosed stockyards and houses for the farm workers. In the third phase, completed by 1855, a piggery and sheep house were added at the north end of the main complex, flanking an extension of the main spine building. These are both circular and top-lit by a clerestory, with an open centre extending down into the basement level, through which waste was removed from the building. A feedstuffs mill, powered by small streams channelled to drive a water turbine, was also added.

In a fourth phase, completed by 1860, a second fodder shed (identical in design to the first) was erected, as well as a shed where sheep were dried off after being dipped and storage space for root crops. Finally, a short distance away a workshop was built with a storage area for ploughing and traction engines, which could also be used when stationary to power ancillary machinery. Goods were transported around the complex by wagons running on a broad gauge tramway. A short distance away, a funicular railway was constructed to transport manure up to a tank on high ground fed by a hydraulic ram located on a specially cut by-pass channel of the River Severn. From here, liquid slurry was distributed around the estate by gravity using a system of copper pipes.

As befitted a project intended to demonstrate how technological advances could make agriculture more efficient, the planning is rational and, indeed, thoroughly classical in its axial organisation. Stylistically, the complex is in what would come to be termed the functional tradition – well proportioned and carefully detailed, and (with the exception of the two houses, handled in a loose Tudor Gothic) lacking any historicising garb. Further research is needed to confirm the authorship, but Poundley is a plausible candidate as someone who, in addition to his attested links with Naylor, was clearly making a bid for that niche in the market. In 1857 he published a pattern book entitled Poundley’s Cottage Architecture with designs for agricultural buildings intended to be suitable for hilly areas of Wales. It included a farmyard that has strong affinities with Home Farm and a design for a double cottage of bungalow form based on iron-framed construction. In 1866 he designed a complex of agricultural buildings for Rowston Farm on Lord Cawdor’s Stackpole Estate in Pembrokeshire and, as we shall see, was himself actively involved in farming.

Home Farm may have been uncharacteristically plain, but Poundley soon showed himself able to reconcile the design of agricultural buildings with High Victorianism at its most exuberant, most notably at the poultry house of 1861. The exterior incorporates timber-framing, jettying and the deep eaves and decorative bargeboards that were to become one of the firm’s trademarks. That same year, Poundley acceded to his former teacher, Penson’s old post of Montgomeryshire county surveyor. Around the same time, he was involved in overseeing the construction of a 3¾-mile branch line from Abermule on the main line of the Cambrian Railway to his native Kerry. Authorised in May 1861 and opened for traffic in June 1863, it was intended to exploit timber and quarry traffic from the Brynllywarch Estate and Poundley’s own venture in breeding Kerry Hill sheep. The station building (in fact located some way short of the village in the hamlet of Glan-Mule) was probably designed by the Poundley firm and quite grandly appointed for a destination with little passenger traffic.

None of these works really justifies the claims that I made at the outset for the firm. But that would soon come with a couple of buildings begun in 1863 in the neighbouring county of Denbighshire. Both of them exhibit a style that seems to have emerged fully formed (unless there are precursors out there waiting to be discovered) and demonstrate a confident handling of the High Victorian muscular Gothic idiom, incorporating the innovations drawn from Italian medieval architecture promoted by John Ruskin and the ‘vigour and go’ of early French Gothic. More research would be needed – assuming it could find the answer at all – to ascertain how the Poundley and Walker firm obtained its mastery of the style. Perhaps David Walker, living in a large, well connected and fast expanding city, was better aware of recent developments in architecture than his business partner, but that for now is speculation.

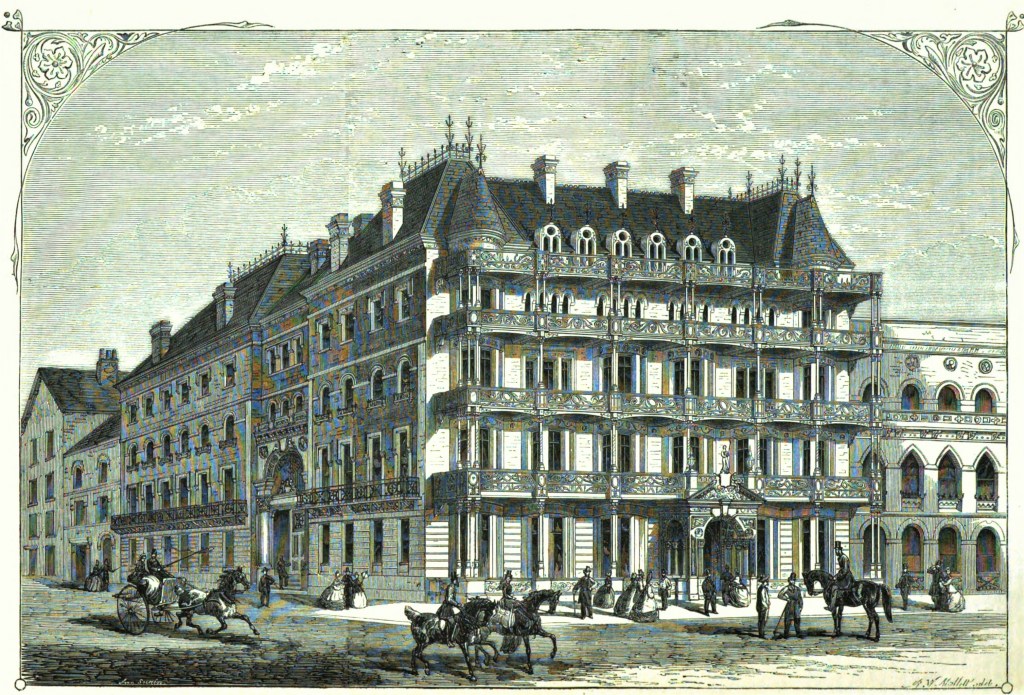

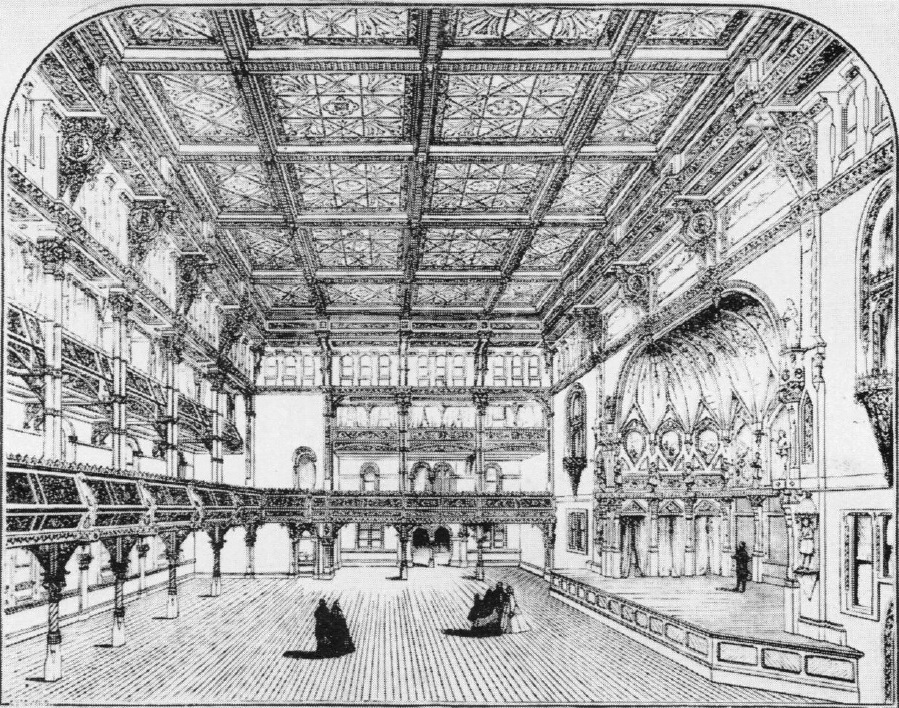

The first of these projects was a complex of civic buildings on Market Street in Ruthin, Denbighshire – a combined town hall, market hall and fire station. It postdates by only a few years the similar complex by R.J. Withers in Cardigan discussed in a recent post, and the comparison is instructive. Like it, the building is deftly fitted into an awkward sloping site. The main administrative block is located at the lower end, taking advantage of the change in height of the terrain to fit in a monumental elevation and dramatic return to a side street. In the Ruskinian line, the ground floor consists of a boldly expressed arcade resting on sumptuously carved capitals, whose tympana are filled alternately with plate tracery and carved reliefs, executed by Edward Griffith of Chester (dates unknown). A bell tower terminating in a hipped mansard roof marks the junction with the market hall, with cart entrances consisting of curious polygonal arches under crow-stepped transverse gables. Internally, it is spanned by arch-braced trusses of bolted timber construction, reinforced by wrought iron tension rods and supporting a clerestory. Beyond is the fire station with two elliptical arches dressed in brown sandstone for the vehicle entrances. A favourite characteristic of the firm’s style emerges here – play in colour and texture, with the rock facing used for most of the wall surfaces contrasting with the smooth ashlar of the dressings executed in a lighter stone. Note also the prominent use of wrought and cast iron detail, extending even to the finials of the tiny dormers of the bell tower.

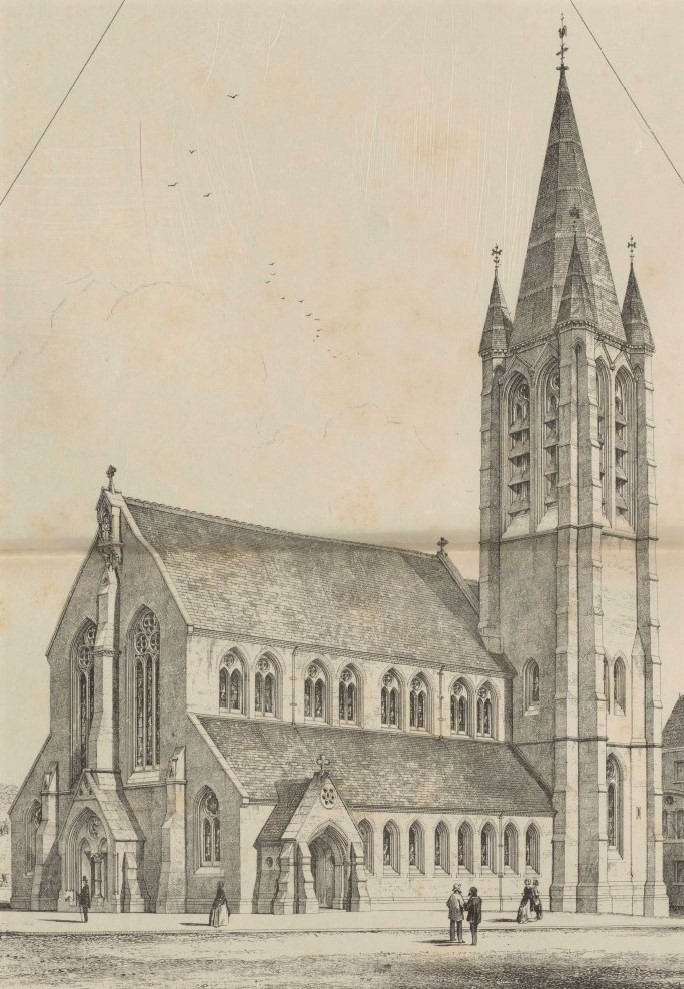

That same year, the practice executed a commission for a new church at Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, a village only a couple of miles outside Ruthin to the east on a splendid hillside site with views over the Vale of Clwyd. In 1848 Joseph Ablett, the owner of Llanbedr Hall, died and left the property to his step-nephew John Jesse. Jesse was shocked to discover that the graveyard was so full that new interments disturbed existing burials, and in response gave not only land to allow it to be extended, but also a new church. It stands a short distance away from its medieval predecessor, whose ruins (it was unroofed and abandoned in c. 1896) are still extant.

It is a simple, two-cell building of modest proportions – a nave of four bays with an apsidal chancel of two – but the designers exploited every possible opportunity to make it a vehicle for really forceful expression in sculptural form, ornament, colour and texture. The use of rock facing and structural polychromy is already familiar from Ruthin town hall, here augmented by the vividly striped voussoirs and further enhanced by the banding of the slate roof. There is plate tracery throughout, even in single lancets. The windows of the apse break through the eaves into dormers, the upper stages of the towerlet, which starts off as a square and turns hexagonal, goes off on the most extraordinary geometrical excursions. Everything is overscaled and exaggerated to the point where it becomes almost a parody of Gothic, an effect underlined by the huge crockets budding from the steeple, bold ironwork crosses and railing to the ridge of the chancel roof. ‘The funny little thing is so powerful… that I feel its preservation is most important, its unique potency being, in my experience, unmatched in so small a compass’, wrote architect Sir Clough Williams-Ellis (1883-1978) to J.D.K. Lloyd in a letter of 2 May 1977.

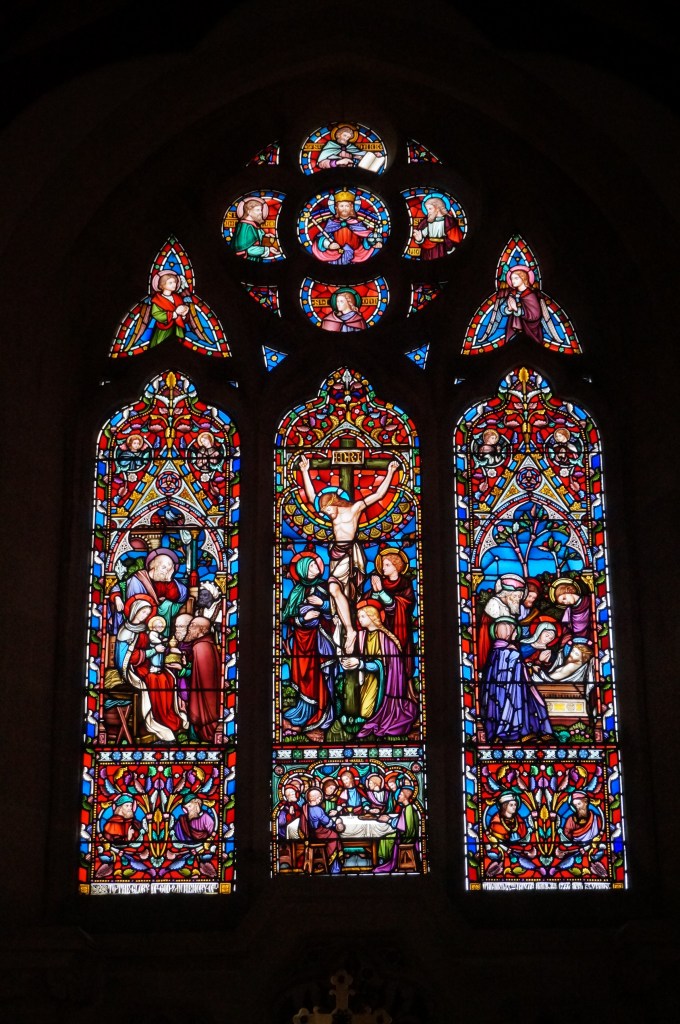

The interior is a little tamer. As usual, the focus is on the east end with the Decalogue boards, Creed and Lord’s Prayer (here all in Welsh) framed in blind openings of cusped tracery with gablets above, all richly adorned with pinnacles and crockets. The pattern of the fenestration means that the reredos squeezed in between them is comically underscaled. Tiles by Maw & Co and stained glass by Clayton and Bell installed at the time of construction (as recorded by an inscription in the tympanum of the vestry doorway) give colour. There is excellent ironwork filling a sound hole through which the organ speaks into the nave and the bold carpentry of the roof structures gives further visual interest.

That same year, the firm designed a new church for the village of Carno, located in a river valley northwest of Newtown (formerly in Montgomeryshire, now Powys). The uncompromising stylistic language is by now familiar. Here, the rock facing is varied with dressed red sandstone, which is used for inserts in the spandrels of the plate tracery. The vigorous impression is marred by the loss of the original timber bell turret, which had to be removed in c. 1978 after becoming unsafe and was reinstated in much simplified form. But for all that, it is a highly rational design compared to Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd – a single volume with unbroken wall surfaces and roofline externally, and no structural division between the nave and chancel internally, just doubled up roof trusses supported on compound attached colonettes rather than corbels. Again, the carpentry of the roof, here with scissor-braced trusses, is a prominent feature of the interior.

In 1864, the firm put up a magistrates’ court on High Street in Llanidloes, (formerly Montgomeryshire, now Powys). Here, the material is the red brick that predominates in the town enlivened with copious constructional polychromy, although most of the west elevation is slate-hung in accordance with a local tradition. The window and door jambs are intricately chamfered, sometimes in two orders. The pièce de résistance is the doorway leading to the courtroom at the rear of the building with a polygonal intrados to the arch and chunky wrought iron door furniture. Lloyd speculates that this commission was the work of Poundley alone, acting in his capacity of County Surveyor, but this wants confirmation.

Around the same time, the firm took on a couple of commissions for country houses. The first is Broneirion at Llandinam in the Severn valley northeast of Llanidloes, now used as the Welsh Training Centre for the Girl Guide Association. It was built for David Davies (1818-1890), a native of Llandinam, whose meteoric career as a contractor had begun in 1846 when he was invited to make the foundations and approaches for an iron bridge over the Severn in the village. This was the work of Thomas Penson (q.v.), the first of three such bridges that he designed in his capacity as Montgomeryshire County Surveyor. Davies’ firm went on to build numerous railway lines in Wales, such as the route from Oswestry through Newton to Machynlleth (for which the Kerry branch was a feeder) and was later heavily involved in the exploitation of the Rhondda coalfield.

Broneirion is a curious building in Poundley and Walker’s interpretation of the Italianate style. Finished externally in smooth ashlar masonry and Roman cement render, it lacks the textural variety of their work elsewhere, if not the sculptural interest – witness the ingenious corbelling out of the top of the bay window where it becomes a gable end and the tunnel-like eaves of the top-floor dormers. Still, it feels a little underpowered compared to the splendid entrance lodge. Just like the church at Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, that building packs a huge amount of variety and invention into a relatively small form. Of particular interest here is the fine joinery of the lean-to porch and bargeboards, a feature that will crop up elsewhere. Next comes Llanbedr Hall. John Jesse, who commissioned the new church of St Peter, died the same year that it was completed. The property was inherited by his son, John Fairfax Jesse, who in c. 1866 commissioned Poundley and Walker to remodel it. Work was not completed until 1874, but for a house with such an involved construction history, the result was rather disappointing – recognisably in the firm’s High Victorian manner, but gone rather flaccid and looking like a much smaller house inflated in its proportions to suit the occasion.

Far more successful is the remarkable group of buildings at Abbey Cwmhir in Radnorshire (now Powys), north of Llandrindod Wells. As the name implies, the village was once the location of a religious house, founded in c. 1176 by Cistercians who, characteristically, had been drawn to a beautiful and secluded location in the valley of the Clywedog Brook. Following the Dissolution, the abbey buildings were plundered for stone and the lands became a private estate. In 1821, the estate was purchased by an art collector called Thomas Wilson, who put up a house in a neo-Elizabethan style, which was completed by 1833. He positioned it overlooking the site of the abbey on the water meadows, which he landscaped to create a pleasure ground. But the expense of all these works ruined him and in 1837 he sold the estate to Francis Philips (1771-1850), scion of an old Staffordshire family that had made a fortune in the Manchester cotton industry. Philips’ eldest son inherited the estate but outlived his father by only nine years, so it passed to his younger brother, George Henry Philips (1831–1886), who embarked on a major building programme.

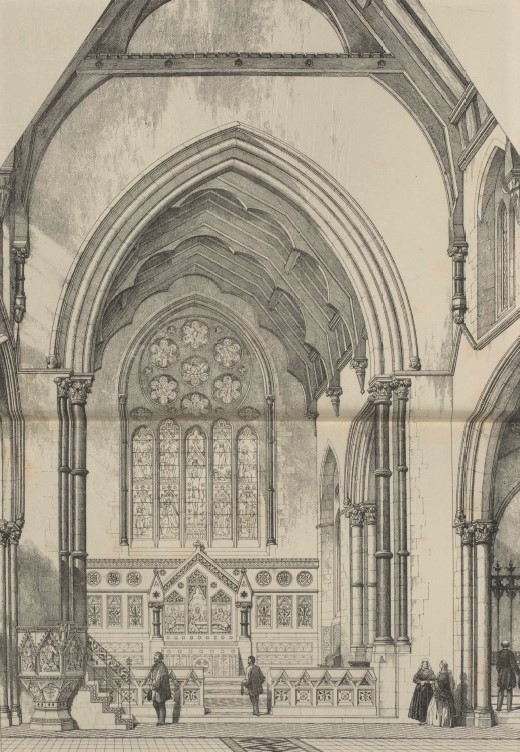

Firstly, in 1866, the church of St Mary was rebuilt on the site of a 17th century predecessor. It is a variation on the theme set by Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd – again a two-cell structure with a short chancel terminating in a polygonal apse and an east window breaking through the eaves cornice into a dormer. Again, there is rock facing, striped arch heads, plate tracery and banding to the slate roof. Though the tower is more massive, there is the same love of geometric invention in the handling of its transformation into an octagonal spire, whose upward progression is interrupted by a ring of colonettes supporting trabeated openings – almost as though the top had been sliced off and this stage inserted as an afterthought. The tympanum of the main entrance is occupied by a relief of the Ascension, based on one discovered during investigations of the abbey ruins.

But the interior has more punch than Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, with much superb quality carving – foliate ornament to the capitals and imposts of the chancel arch, diaper work to the panels of the pulpit. There are the polished granite column shafts so beloved of High Victorian Goths and much vividly patterned tilework on the floor of the chancel, rising in the sanctuary to dado height. The fenestration of the apse is resolved much more successfully by making the central window wider than its neighbours. All the windows in the chancel are glazed with excellent quality stained glass by Robert Turnill Bayne (1837–1915) of Heaton, Butler and Bayne. This was installed at the time of construction, as was the glass in the west window by Clayton and Bell. A complete set of original fittings survives and the whole adds up to a confident, strident and colourful period piece that is remarkable for its aesthetic integrity and excellent state of preservation.

In 1867, work began on remodelling the hall, which lasted until at least 1870. Reputedly it incorporates fabric from its predecessor, but quite how much and to what extent this determined the outcome is impossible to say without further research. There are signature details such as the chunky colonettes with outsize foliate capitals and striped arches and relieving arches, although the walls are all finished in smooth, uniform ashlar rather than rock-faced. The most remarkable feature is the ensemble of three major and three minor gables to the long garden front and J.D.K. Lloyd had good reason to say that ‘This remarkable house gives a first impression of being subsidiary to the bargeboards!’ But for all the ingenious detail, there is a slight sense that the architects’ imagination flagged when dealing with a building on so large a scale, which offered less opportunity for treatment as a discrete sculptural form. This can be checked through comparison with the delightful Keeper’s Lodge a couple of miles down the valley to the east, which must be roughly contemporary with the Hall.

The work at Abbey Cwmhir brought to a close the Poundley and Walker partnership, which was dissolved in 1867. Both men remained in practice, although Poundley, probably the older of the two, was perhaps less active and may have concentrated on surveying work – one deduces as much from the paucity of later commissions, although only further research could confirm the hypothesis. His only son, John Edward Poundley (1839-1917) was agent to the Brynllywarch Estate and several others. Walker seems to have specialised thereafter in ecclesiastical work, designing a number of new churches and restoring several others. He was something of an antiquarian, writing papers for Montgomeryshire Collections on the late medieval rood screens in the churches of Newtown, Llanwnnog (which he restored in 1873) and Llananno (where he reconstructed the entire building in 1877-1878). It is competent, decent architecture, but not on a par with his output of the preceding decade.

Perhaps this was the result of changing tastes and incipient reaction against the High Victorian Manner. Perhaps Poundley was really the driving force in the practice. Or is it that the work of the 1860s was the product of some alchemical symbiosis of their respective talents and temperaments, which could not reach the same heights when they were working in isolation? We cannot know, but we can be glad that whatever it was lasted for long enough to bequeath to us a remarkable architectural legacy whose verve and dynamism bear witness to a vigorous and dynamic age.