This is a figure who deserves a long and detailed write-up. That he is not going to get one in this post is the result of a happy circumstance, which is that this blog is about to be supplanted – and on this occasion, by its own author. Last week I received the news from Liverpool University Press that it has finally given the go-ahead to a proposal for a monograph on the life and work of architect Joseph Peacock (1821-1893). The book will be based on the dissertation that I submitted back in 2015 for a Master of Studies in Building History at Cambridge University, and it will form part of a long-term joint project by Historic England and the Victorian Society. Back in the 2000s, the Twentieth Century Society initiated a programme of monographs on twentieth century architects, which was initially published in collaboration with the RIBA and has now been taken over by Liverpool University Press. The result has been an impressively well produced series of studies of figures on whom hitherto there had been no really authoritative literature. The Victorian Society had long wanted to do something similar and last year the first volume appeared in its own series devoted to the life and work of John Francis Bentley, to be followed next month by a monograph on A.W.N. Pugin. I have to thank the eminent architectural historian and general editor of the Survey of London, Andrew Saint, for suggesting the idea and encouraging and supporting me in pursuing it. He was my supervisor for the dissertation, and I count myself very lucky to have had the benefit of his expertise and erudition, which with he was unstintingly generous.

At the moment I cannot say when the book might appear, although I doubt it will be before 2022. Though most of the research has been done, there is plenty of work ahead recasting what I wrote six years ago and turning it into publishable form. Back then, I began by producing a chronologically arranged catalogue raisonné, topped by a biographical sketch and tailed by an essay assessing the significance of Peacock’s work in the context of his time. At that point, I was thinking in terms of a reference source to assist future architectural historians and heritage professionals needing information about his work. But I think the subject would be more usefully served if I were to rework the structure to deal with Peacock’s output by building type, and such an approach formed the basis of the book proposal. I submitted this back in July and one of the reasons why it has taken until now to hear the outcome is that there was a certain amount of soul-searching on the part of the publisher and Historic England as to whether Peacock was a sufficiently interesting figure to warrant a monograph.

Closing in on my quarry

In some of the posts that have appeared here, I have tried to give as comprehensive an account as I can of the life and work of an architect on whom there is no reference work. For obvious reasons, I won’t be doing that on this occasion. Instead, I would like to explain how I came to be interested in Peacock and why I think he is worthy of your, Historic England’s and Liverpool University Press’s attention. For a long time, all that I knew of him was that he had designed a couple of churches in central London. St Simon Zelotes on Milner Street in Upper Chelsea, just off Cadogan Square, built in 1858-1859 enjoyed a certain amount of renown among the cognoscenti for being a particularly quirky bit of High Victorian Gothic. Holy Cross, Cromer Street near King’s Cross Station could not compete on that score (it is Peacock’s last known work, built in 1887-1888), but nevertheless had caught the attention of Ian Nairn, whose description in Nairn’s London is little short of rapturous. They had been on my ‘To see’ list for some time, but I had never attempted to set foot in either, and in fact both are usually kept locked outside service times. That situation changed in 2012, by which point I was working for the Diocese of London. An application was submitted by the parish of St Simon’s for a minor reordering project aimed at equipping the church with a tea bar, and a meeting was organised at the church. Once the business of the site visit had been completed, I was able to explore the building on my own, and the bright, late-summer afternoon sunlight showed it at its best. It is not a piece of architecture easily to be forgotten. Goodhart-Rendel describes the church at some length in Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era – he grouped Peacock with E. Bassett Keeling and R.L. Roumieu as the figures who had been responsible for the most extreme attempts in the 1860s ‘to debauch the Gothic Revival’ – and rhapsodises about its creator’s prodigious powers of invention.

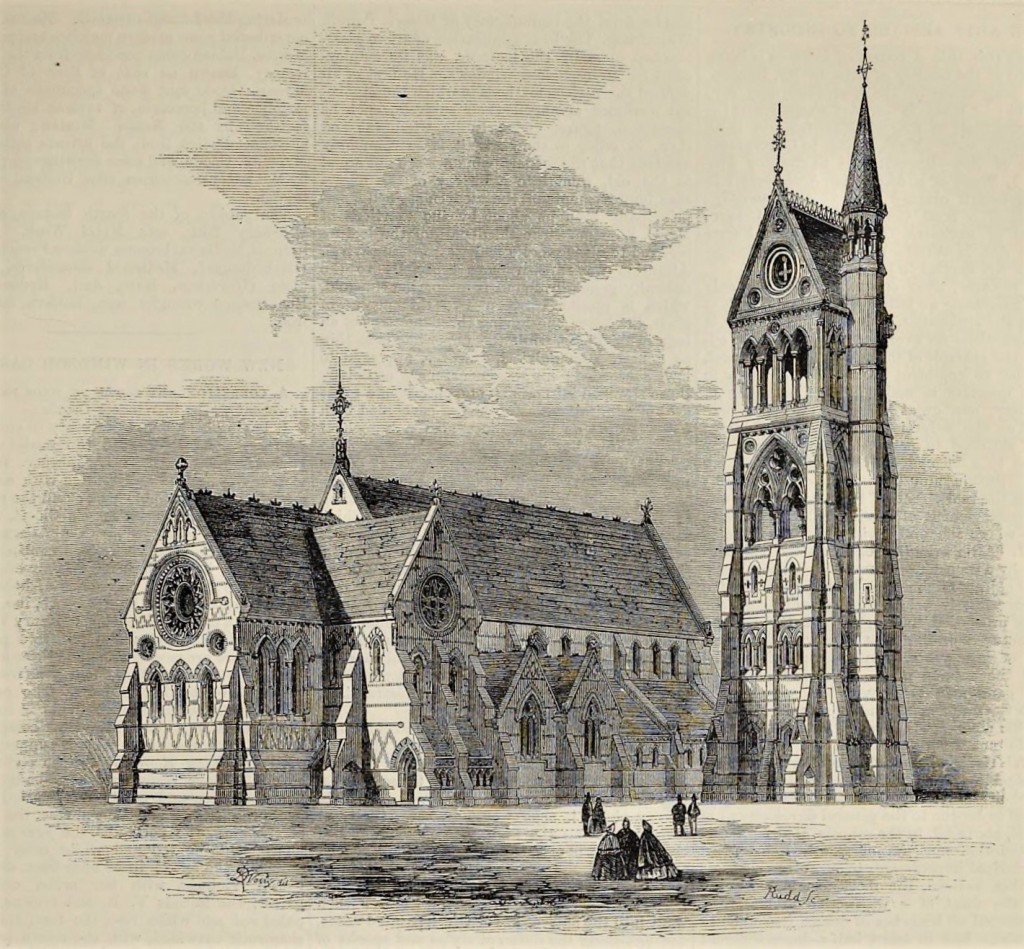

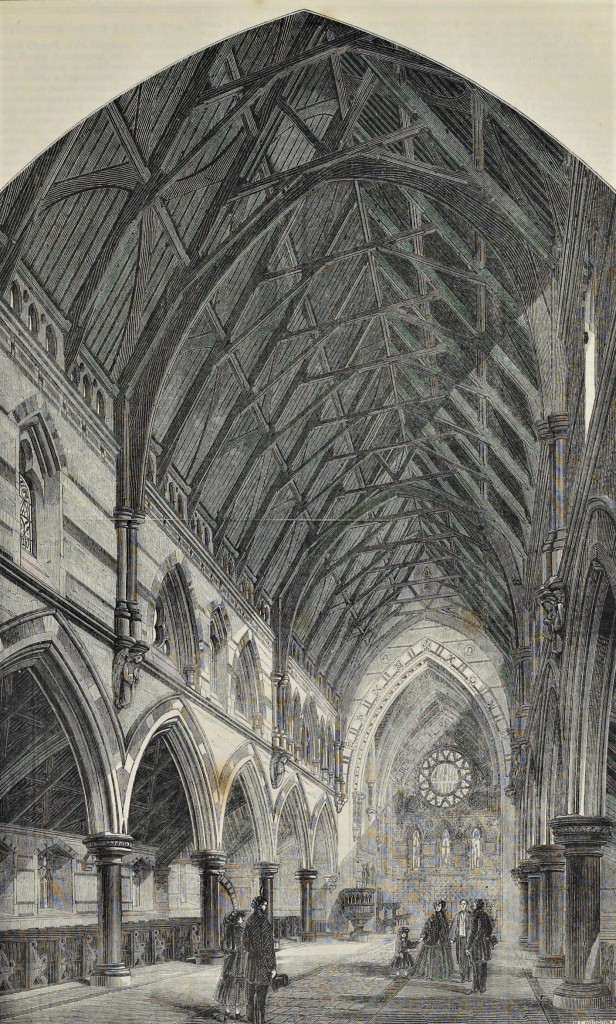

This immediately set me wondering about what else Peacock had designed and whether there was anything in his output that stood comparison with St Simon Zelotes. By happy chance, there was a copy in my then-office of Volume 24 of The Survey of London, which reproduced an artist’s impression first published in The Builder in 1864 of Peacock’s design for St Stephen’s, Gloucester Road in South Kensington. Here, unquestionably, was something to rival St Simon’s in power and wilfulness. A search on Images of England (the now superseded illustrated version of the National Heritage List for England) revealed that he had designed a couple of churches in the suburbs of Derby – St James the Greater in Rose Hill and St Thomas’s in Pear Tree – but what little could be made out in the small, poor quality images did not look quite so promising. The most surprising thing about the second church was that it was neo-Norman, a very late instance of the style for its date of 1881. Peacock nagged away at me over the course of the next few months until in November 2013 – by which point I had already commenced the Cambridge MSt – I chanced upon a copy of Gavin Stamp’s Lost Victorian Britain, which included a description, accompanied by photographs taken by John Summerson, of St Jude’s, Gray’s Inn Road in St Pancras, a real bonanza of Rogue Gothic built in 1862-1863. Its qualification for inclusion in the book was that it had been demolished, and as far back as 1936, a time when the Diocese of London was weeding out buildings that were surplus to requirement in over-churched inner-city areas and using proceeds from the sale of the sites for ministry to the new suburbs of Metroland.

During the first year of the MSt, I had to find a subject for the second-year dissertation. My curiosity about Peacock led me to wonder whether he might be a viable choice, but I was anxious about the possibility of treading on someone’s toes. There is a substantial amount of very scholarly literature which gives authoritative accounts of major figures – I am thinking, for example, of the doctoral theses on James Brooks and J.D. Sedding – but has yet to be published. I contacted Andrew Saint and Gavin Stamp to pick their brains and was much encouraged by the tenor of their replies: ‘We know of nothing, but if the subject appeals then by all means go for it’. A few sessions in the RIBA Library in the spring of that year gave me enough material to put together a research proposal, which was approved at the end of the first year of the course. Work began in earnest in late summer 2014, but before long I had exhausted the mine of readily available information. There were scraps to be wheedled out here and there, but all too often they raised more questions than they answered. Sometimes they led to new discoveries, something they led me up blind alleys. On my first session in the London Metropolitan Archives, I investigated contract drawings for schools in Tooting and Wandsworth. My elation at seeing genuine artefacts from Peacock’s office quickly turned to dismay on discovering that the drawings had been filed without any accompanying papers that might shed light on the buildings that they showed. Where exactly had they stood? Did they survive? Had the designs even been executed? Answers to all these questions were obtained in due course, but only after (in these particular instances) long sessions on weekday evenings after work in the Wandsworth Local Studies Library. During the course of my research, I travelled widely – to sites and archives in several London boroughs, Essex, Derbyshire, West Sussex, Northamptonshire, Surrey and Oxford. There were numerous instances of serendipity. But there were also long, lonely and sometimes fruitless slogs. I began to understand why a fellow student in my cohort had observed with some feeling, ‘You have to kiss a lot of frogs in archives’.

A life pieced together

The most extensive single source of information about Peacock was a curious item in the RIBA Collection called the Jeffrey Monk papers. It consisted of six typed A4 sheets, accompanied by a substantial amount of correspondence, photocopies and handwritten notes. Monk explains that his account was written to start the 125th anniversary celebrations of St Stephen’s, Gloucester Road, which occurred in 1991. But the task had clearly occupied the author – about whom to this day I know nothing – for a lengthy period, since there was correspondence going back to 1979, a reminder of how slow and laborious such research could be in pre-internet days. It was the work of an amateur scholar and many of the claims made in it needed to be tested, but it did prove invaluable in starting to assemble biographical details about Peacock, on which all architectural historians to take more than a passing interest in his work had thus far drawn a blank. He remains a shadowy figure and I have yet to discover a portrait of him, but what I know of his life so far can be summarised as follows.

Peacock was born and brought up outside Godalming in Surrey. He was the fifth of seven children born to John Peacock (1781-1869/70) and Elizabeth, née Lucas (1782-1868). It seems likely that Peacock’s choice of profession is explained by his mother’s background. Her paternal uncle, one Joseph Lucas (1739-1807), was a successful merchant-venturer in the South Seas whaling industry. He invested heavily in property, much of it on the then-rural fringes of London, although of increasing interest to developers as the metropolis rapidly expanded out into Middlesex and Surrey. It needed someone to administer it, and one infers that this prompted the family to steer the young Joseph Peacock towards the profession of surveyor. Joseph Lucas had resided at Heene House, located in a rural hamlet absorbed during the 20th century into the coastal sprawl of Worthing, which on his death he bequeathed to his younger brother John Lucas (1775-1852). Very likely it is through this connection that Joseph Peacock obtained a pupillage with the Hides. Edward Hide (c. 1772-1858) was a builder and surveyor who did a small amount of architectural work in the area, most notably Worthing’s Theatre Royal, and his son Charles (c. 1810-1876) became the town surveyor. Unless more information comes to light – and for the moment everything rests on the identification of Peacock in the 1841 census as an ‘Architect’s Assistant’ residing with the family – it is impossible to do more than conjecture about his early training, but in a sense this does not matter, as it seems unlikely in any case that there is much about the period in Worthing that would explain why he ended up becoming a rogue. According to an obituary in the RIBA Journal written by his former managing assistant Walter Dewes (1855-1937), ‘After serving his articles… [Peacock] was engaged upon the Tithe Survey and also surveyed for different railway lines’, a career path familiar from the biography of his fellow-rogue, R.L. Roumieu.

Peacock seems to have embarked on an architectural career in his late 20s. One has to be a little careful, because for the moment once again everything rests on a single piece of evidence and once again it comes from the census. In 1851, he is recorded as living at No. 75 Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury at the same address as the architect David Brandon (1813-1897). As we have seen in the post on Shire Hall in Brecon, at that point Brandon was in partnership with Thomas Henry Wyatt (1807-1880), running a large and prolific architectural practice, and it would be no surprise – although for the moment this is speculation – to find that Peacock ended up there as a junior. It would have been mutually beneficial: they were in need of extra hands to manage the enormous workload and he needed a chance to cut his teeth in Gothic. I have a hunch, although so far have been unable to substantiate it, that Peacock may have had a hand in the design of the splendid little church of St James in Cranmore East in Somerset when it was rebuilt on an ancient site in 1846 (the building was made redundant in the mid-1980s and now a residential conversion). It is nominally attributed to Wyatt and Brandon, but is some way above the practice’s usual standard for the period. There is a good deal of wilful detailing, such as the nook shafts to the belfry stage of the tower, that crops up later in Peacock’s independent work.

In 1850, Peacock became an Associate of the RIBA. By January 1853, when he began work on the restoration of St Andrew’s, West Tarring (another village absorbed into the Worthing sprawl), he had set up in independent practice at No. 15 Bloomsbury Square, where he also resided. And there he stayed put for at least 30 years, moving only at the very end of his life to No. 46 Park Street in Mayfair. His biography was uneventful. He handled work mainly in the London area, and, with the exception of the two Derby churches, the few geographical outliers can easily be explained by family or professional connections – or at any rate one can construct plausible hypotheses based on them to suggest how they might have come about. He became a Fellow of the RIBA in 1859 but seems not to have moved very extensively in professional circles, nor, indeed, to have chased architectural work with any great alacrity. Even allowing for the fact that his practice was apparently never large, it is difficult to reconcile his relatively modest output with an estate valued following his death at £38,629 14s. 5d, and it seems likely that surveying provided the mainstay of his income. In addition to the Lucas family’s portfolio, he was also surveyor to the estate of St John’s College, Cambridge in Kentish Town, overseeing the residential development of the land in the late 1870s-early 1880s, and there are quite possibly other surveyorships waiting discovery. He married very late in life and there were no children.

The youthful rogue

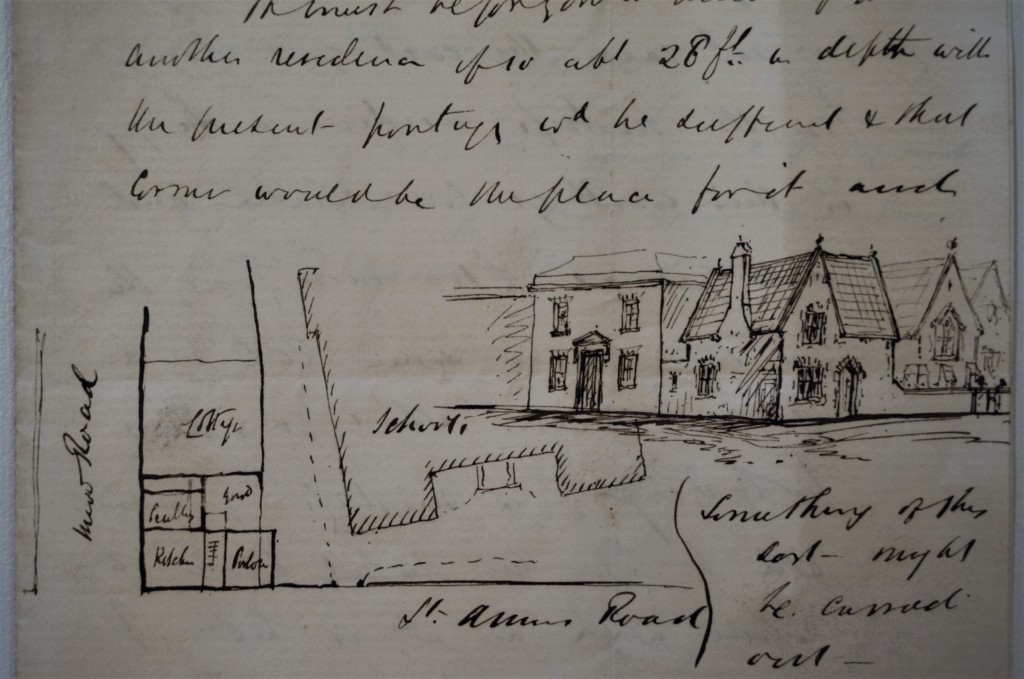

St Simon Zelotes begs the question of how Peacock acquired such an original and fertile architectural imagination. The answer is to be sought in a quartet of schools in south London executed during the 1850s between the West Tarring job and the commission for what was his first new church. Occasional quirky details leavening the otherwise fairly orthodox Puginian design of the Tooting National Schools (1854-1855) erupt at the next work. The National Schools in the area of Lewisham now known as St John’s went up in 1855-1856 on the Lucas family’s Deptford New Town Estate, a triangle of land in between Lewisham High Road and Deptford Broadway, to which Peacock was agent and surveyor. The planning and massing of the school were Puginian inasmuch as the various components of the design were clearly articulated, but the treatment was much exaggerated for picturesque effect to produce a restless, expressive outline with constantly varied elevations that changed with every new viewpoint. The roofline of dormers and tall chimneys was vivid enough, but what really caught the eye was a tall bell turret in the angle of the girls’ and infants’ schools, apparently composed entirely of intersecting buttresses and supporting a bell-cote set at 45 degrees to it with a tall spire supported on thin barley-sugar columns. The design illustrates perhaps more clearly than any other early work in Peacock’s career the versatility of the idiosyncratic architectural language for which St Simon Zelotes is so celebrated. Though confident and imaginative statements of their idiom, the two schools that came after it for the parishes of St George’s in Nine Elms (1856-1857), another project on a Lucas family estate, and St Anne’s in Wandsworth (1858-1859) do not quite match it for originality. Three of these buildings have been completely lost and the sole survivor, the Wandsworth school, was much simplified when rebuilt after war damage. This sad record goes some way to explaining the obscurity of Peacock’s professional origins.

Nevertheless, Peacock had hit his stride, and for the next 15 years or so was at the height of his powers. The most important commissions executed between the late 1850s and the early 1870s are all ecclesiastical, and almost all of them are brand-new churches. He did not involve himself much in the restoration of ancient churches and what little work he did in this vein was generally fairly low-key, the only exception being the new chancel with its delightful tower-like organ chamber that he added in 1871-1872 in an idiosyncratic brand of neo-Norman to the church of St Michael’s at Mickleham north of Dorking in the Surrey Hills. St Simon Zelotes is the best preserved of all the churches and it was for this reason, along with its architectural quality, that in 2014 I put it forward for a listing upgrade, drawing in my application on the research that I had already begun to compile. I was successful: in 2015 it was raised from Grade II to Grade II* (i.e. from the basic category covering around 92 percent of listed buildings to a category covering only around 5.5 percent deemed to have ‘more than special interest) and the revised and expanded list description can be seen here.

As with the schools, so with the churches – had Peacock’s work been less ill-starred, we would appreciate better his talent as a designer. But St Stephen’s, Gloucester Road (1866) was destined to remain without its tower and, after it became very Anglo-Catholic in its churchmanship, the interior was much altered in a manner which, although it does not altogether efface, certainly mutes Peacock’s aesthetic. St James the Greater in Derby was also executed without its powerfully and originally treated tower, then badly vandalised in the 1990s after being made redundant and finally compromised by its conversion about 15 years later to a rock-climbing centre. A magnificent and somewhat enigmatic scheme for a Tractarian ‘holy village’ commissioned by Scottish Episcopalians in Perth was fated mostly to remain on paper, and the school – the only part of it to be executed – was demolished as recently as 1995.

Decline or adaptation?

‘In his later days he became badly infected with good taste’, opined Goodhart-Rendel rather disdainfully of Peacock’s work from the 1870s and 1880s. It is true that he tamed his brand of Gothic (which must have been starting to look rather old-fashioned, although he never abandoned it entirely) and indeed concentrated less heavily on church work, but his output from this period is interesting for what it reveals about an architect trying to readjust to changing circumstances. The vestry and mission hall that he added to Hawksmoor’s church of St George in Bloomsbury in 1875 is, surprisingly, an accomplished piece of classical design, but the choice of style can probably be explained by that of the host building, even if it was the sort of concession rarely made at a time when English Baroque was not generally well regarded.

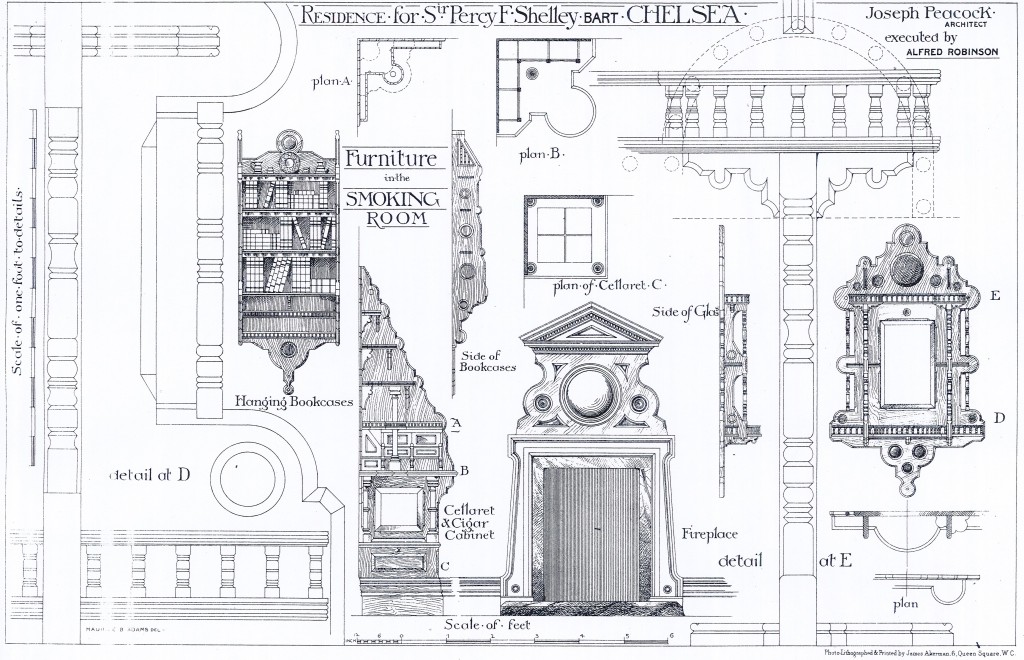

The following year Peacock designed a mansion at No. 1 Chelsea Embankment for Sir Percy F. Shelley (1819-1889), son of the poet. Although Peacock had overseen the construction of plenty of more modest housing, he was hardly an obvious choice for the job and how he landed the commission remains a mystery. It is possible that it came about as a result of his Worthing connections – his client’s great-grandfather, Sir Bysshe Shelley (1731-1815), resided at Castle Goring outside the town. This is a highly individual country house with contrasting Graeco-Palladian and Georgian Gothick fronts built in c. 1795-1815 and designed by John Biagio Rebecca (c. 1777-1847), who was based in the town and was also responsible for a number of buildings in the vicinity, including St Paul’s Church, a joint project with Edward Hide. Shelley’s diaries survive in the Bodleian Library, but although prolix in their coverage of minutiae such as minor ailments and the weather, are frustratingly uninformative about the construction of the house, so until it can be corroborated by documentary evidence the link must remain conjectural.

The mansion was a rather ponderous design in a free neo-Jacobean of the kind that had enjoyed a vogue 30-40 years previously – conceivably, given his lack of experience in the field, Peacock fell back on his time in the Wyatt and Brandon office, which had produced numerous essays in the style for country seats. More interesting was the private theatre that he built for Shelley on nearby Tite Street in 1879, now known only from a tantalising description by the correspondent of an unidentified theatrical publication, which makes it clear that the interior was phantasmagorical stuff. Unfortunately, it was short-lived. Shelley’s purchase of the site had been subject to a covenant prohibiting the proposed theatre from being used for any public performances. Around three years after its construction, following a public announcement of a play to be staged there, a neighbour brought a case against Shelley. It seems to have been sour grapes on his part and the magistrate at Westminster Police Court fined Shelley the token sum of 1 shilling. But the damage was done, the theatre was never used again and, following her husband’s death, Lady Shelley sold the site for redevelopment in 1896. No. 1 Chelsea Embankment was demolished just 12 years after that.

Around the time the Shelleys took up residence, work was under way at several sites on Tite Street on executing the innovative and progressive designs that E.W. Godwin had produced for artist’s residences there, including James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s White House. They may well have invited unfavourable comparison with Peacock’s effort and perhaps this was why in 1879 he stepped into the waters of the Queen Anne style for the first time with a design for the parish school of St George’s on Little Russell Street in Bloomsbury, which faces his slightly earlier vestry and mission hall on the opposite side. The narrow street frontage might well be that of a residential property. The building was converted to flats before it was listed in 1999 and not much can be gleaned about the remainder, other than that the rear elevation to Gilbert Place is a good deal plainer, while nothing at all is currently known about the interior.

The same year that work began on St George’s School, Peacock was commissioned to design new premises for the Bloomsbury Dispensary for the Relief of the Sick Poor, which provided free medical assistance, mainly to impoverished tradesmen, workmen and servants, many of whom originated from the notorious Rookery of St Giles a short distance away. Being not only a local resident, but also a member of the governing committee and a subscriber, Peacock took a keen interest in the institution. Built in 1880-1881 on a site at the corner of Streatham Street and Bloomsbury Street, the exterior of the Dispensary embodied all sorts of favourite devices of the Queen Anne style, such as Dutch gables, split pediments, doorcases with overlights and large mullion and transom windows, but did not quite cohere as a design. Again, nothing is known of the interiors, this time because the building was wrecked during the Blitz. It was not rebuilt after the War and seems to have disappeared largely unrecorded. As far as is known, Peacock did not repeat the experiment.

In addition to schools, churches and surveying, Peacock also had a minor line in designing warehouses. This begins with Sufferance Wharf on Bermondsey Wall, built in c. 1864. The sole evidence for the attribution is details of a tender for ‘Buildings in Bermondsey’ published in the May of that year in The Builder; but the case was strengthened by the discovery that, although the client was nominally a firm of wharfingers called Clift, Nicholson & Co, the site seems to have been owned by merchants and ship-owners called Lucas and Spencer, in which Peacock’s great-uncle had been a senior partner. Sufferance Wharf was demolished at some date after 1975, but is reasonably well recorded in insurance plans and photographs, which show an imposing structure with a central block of five storeys flanked by wings of four. The river front was symmetrical, but sparingly treated – it was good building rather than art-architecture.

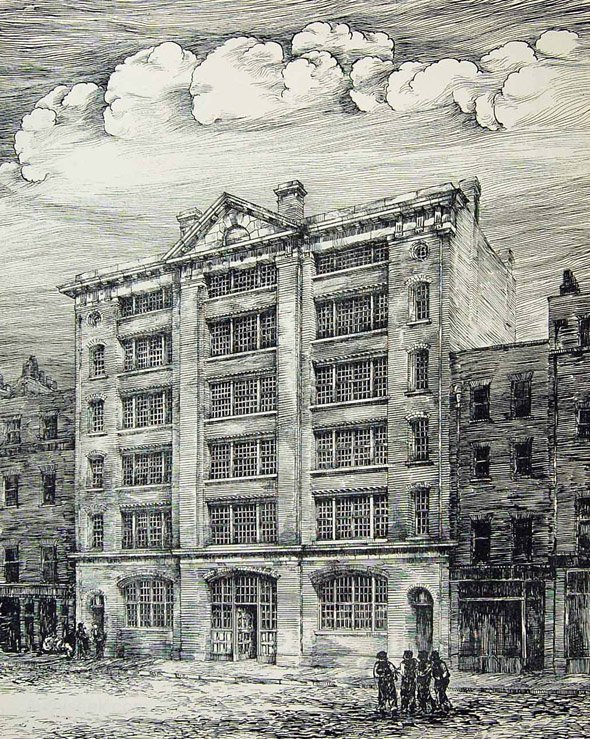

But Peacock was allowed freer rein in commissions for two city-centre warehouses not far from his office, both built in c. 1884, which came about through an association with a firm of iron and hardware merchants called Pfeil, Stedall and Son. The street front of the warehouse on High Holborn was treated in a stripped classical manner, while that of the complex on Macklin Street incorporated minimal Gothic detailing. The former included office accommodation, while the latter housed not only storage space for the company’s goods, but also a delivery depot. Rather like Crosse and Blackwell’s premises at No. 111 Crown Street featured in the post on R.L. Roumieu, the stables were on the first-floor, with access via a ramp in two flights, and there were living quarters for staff on the top. The construction of both buildings made extensive use of structural ironwork and steelwork. The High Holborn warehouse was demolished in the 1950s, but the Macklin Street warehouse survives and was identified with the scheme published in The Builder by Andrew Saint in late 2014. It is unlisted, but, depending on how well it survives behind the street front (easily checked by comparison with the plans and sections accompanying The Builder’s report), may well merit statutory protection and indeed is one of a number of potential candidates for listing identified by the dissertation.

Conclusion

The dissertation was submitted in April 2015. The viva took place in July and my examiners were the late Gavin Stamp and Tim Brittain-Catlin. Both are luminaries in architectural historiography of the 19th and 20th centuries and defending my writing to them was a daunting prospect. I did not expect an easy ride. They rather lulled me into a false sense of security by allowing me to speak unchallenged, explaining how I had come to choose the subject rather in the manner that I have done above. After a while, I began to worry that I might be about to exhaust my topic. Then came the killer blow: Gavin turned to me and said, ‘We couldn’t help wondering whether Peacock wasn’t actually all that good an architect’. This was a shock and it caught me rather off guard. It still rings in my ears. After all, who would not be taken aback by the insinuation that he might have wasted months of hard work on the study of a figure who does not deserve the attention?

Yet it is a legitimate question. That Peacock conformed to Goodhart-Rendel’s definition of a rogue architect in producing neither a school in his own time nor followers among the succeeding generation is not in doubt, but in the wider scheme of things, is that a testament to individuality or to insignificance? True, he may have been unlucky in being denied the chance to bequeath much of his output to posterity, but that alone cannot explain his obscurity. The qualification ‘unjustly’ prefixed to so many neglected figures is not always warranted. Equally, renown can easily outlive the buildings that earn it, especially in the age of the mechanical reproduction of works of art, and there are enough architects who have exerted a huge influence through designs that never got off (and indeed may never have been intended to leave) the drawing board – Antonio Sant’Elia in Italy just before World War I and Ivan Leonidov in the Soviet Union of the 1920s and early 1930s, for example.

A cynic may object that I was hardly likely to conclude otherwise, but I do not think that the effort invested in giving a full account of Peacock’s life and work was wasted. Any creative figure’s works need to be placed in the context of his or her own life before one can start assessing them against any other criteria. The big discovery about Peacock was that his idiosyncratic brand of Gothic evolved through the design not of churches, but of schools. Though the remainder of his career to some extent bears out Goodhart-Rendel’s charge that he lapsed into dullness, it is still interesting as a demonstration of how the purveyor of strong meats that enjoyed such a demand during that decade responded when the appetite for them dwindled. We can, after all, only guess as how the other members of the ‘trio of architectural rakes’ comprising Peacock, Keeling and Roumieu might have coped with the same challenge. Keeling reinvented himself after the disaster of the Strand Music Hall episode, but that line of development was curtailed by his untimely death. Roumieu had already reinvented himself once before launching himself into high Victorian Gothic and was dead before the close of the 1870s.

Nevertheless, the 1860s (give or take a few years at either end of the decade) mark a distinct episode in these architects’ careers when they were at their boldest and most inventive, and Peacock’s achievement is best evaluated through comparison with his peers . To Goodhart-Rendel, they had all started from the same point, but proceeded outwards in different directions: ‘No concert seems to have existed between Messrs. Roumieu, Peacock and Keeling… the general resemblance between the results of their attempts was due not to the similarity of their efforts but to the identity of the victim’, i.e. the revived architecture of the Middle Ages. That is, at any rate, one way of understanding what happened. Yet as I pondered the matter while writing my conclusion, I came to think that each one of the rogues in fact represents a kind of ‘shadow’ counterpart of mainstream currents in the Gothic Revival, which they reflect in a distorting mirror – Peacock the archaeologically correct Gothic of Pugin and Carpenter, Keeling the muscular Gothic of Street and Scott, Roumieu the Middle-Pointed at which just about every Victorian architect tried his hand.

This is not to downplay the importance of individual temperament, of course, and that is one more reason why biographical overviews are so vital to our understanding of the architects involved. But though one may hesitate to call it a school – they worked in parallel rather than as collaborators – I still feel that ultimately the achievement of these figures is collective, made through their rich, diverse and imaginative contribution to the architecture of the 19th century. While it may not be possible to make grand claims for an individual, discounting or ignoring any one of them dims the colours of a vivid picture. Rather than pandering to a public ‘mood for stimulation and excitement’, the charge levelled by Goodhart-Rendel, these were architects who deepened and expanded the expressive range of revived Gothic through their experimentation and risk-taking. Arguably, they went furthest in creating a style which, if not ‘of its time’ in the sense of being representative of the Victorian age as a whole, was at least a distinctive expression of a short, but furious and entertaining period. That, at any rate, is my thesis. Whether you agree is something I will leave you to decide from my book, as I hope you may have the chance to do by this time next year.

Interesting

Do you have any information on construction methods used by Joseph Peacock

St Stephens Gloucester Road has similar construction to an building I am researching in the west country

Please contact

John Keenan

CIRCA Trust Archives

0117 968 78 50

LikeLike

What methods in particular interest you and what is the construction at St Stephen’s to which you refer? It’s a frustrating building to research because unless there is information in the parish’s own records (which I haven’t yet investigated) it seems to have left barely a trace in the archives.

LikeLike