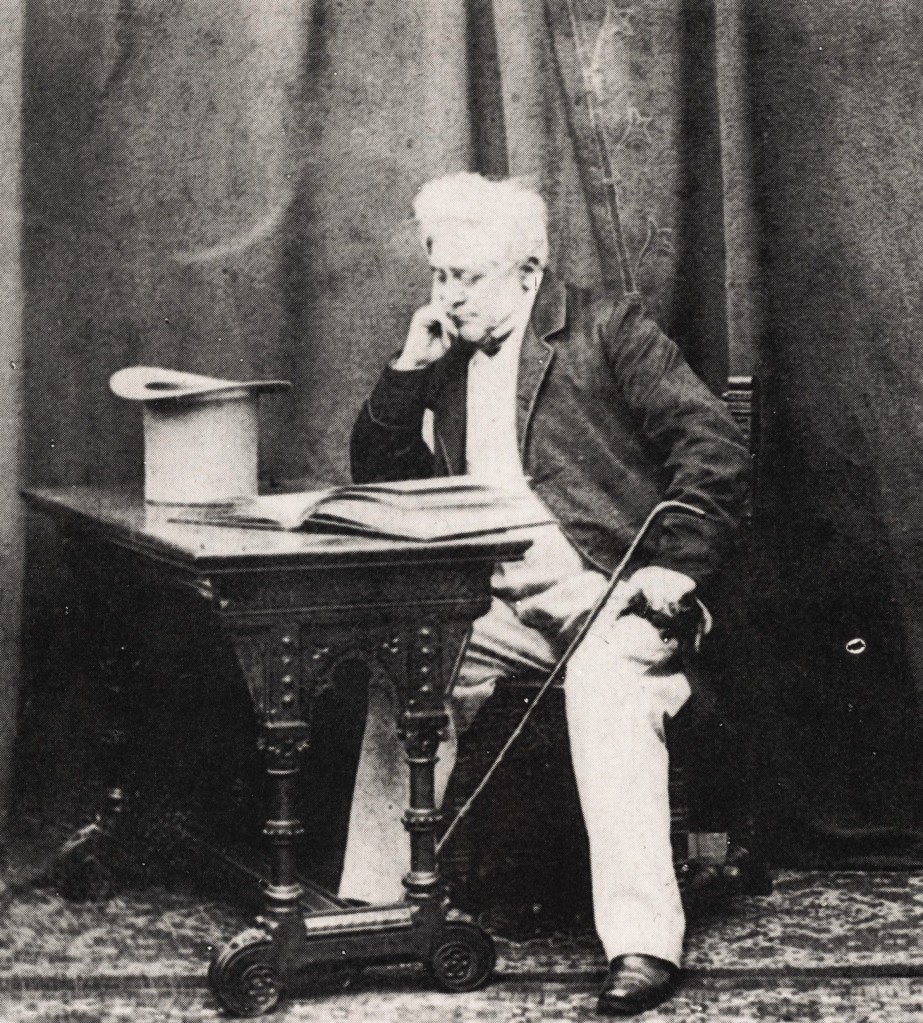

For many of the architects featured in this blog, single posts running to something in the region of 15 pages of copy is sufficient to give a reasonably comprehensive account of their careers. Further research might bring to light previously unknown works and thereby flesh out the picture, but is unlikely to yield anything that will change our perceptions greatly. With Samuel Sanders Teulon – who has already been mentioned in passing here more than once – the case is not so simple. He was a major figure, who designed prolifically and built throughout the country. His work has impressed academics and aficionados alike as being strongly, even rebarbatively individual. It is not architecture likely to leave observers indifferent. And yet for all the vilification and praise it has drawn as attitudes to Victorian architecture changed during the 20th century, we are still not much nearer to understanding why Teulon designed as he did, or indeed even able to assess his work on the basis of a comprehensive survey.

This is not to say that he has been ignored or underrated by architectural historians. Sir Charles Eastlake described at some length and with admiration Teulon’s final church of St Stephen’s, Rosslyn Hill in Hampstead, which was approaching completion at around the time that A History of the Gothic Revival was published. Nearly 100 years later, when the great re-evaluation of Victorian architecture was under way, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner and other authors of The Buildings of England series often dwelt on his buildings at length, recognising him as a name to conjure with. ‘The body of the church restored by S.S. Teulon, 1852-1853’, wrote Ian Nairn of St Margaret’s in Angmering in the first edition of the Sussex volume. ‘Experienced users of The Buildings of England will know that this is likely to be the most important visual fact about the church. It is: Teulon had a field day…’ Mark Girouard wrote equally appreciatively about him in The Victorian Country House, first published in 1971, including a detailed account of his remodelling of Shadwell Park in Norfolk.

But no one has done Teulon a service as advocate for his work to compare with Matthew Saunders, the architectural historian and conservationist who until recently was Director of the Ancient Monuments Society and the Friends of Friendless Churches. His first work to appear in print – as far as I am aware – was The Churches of S.S. Teulon, which was published in 1982 by The Ecclesiological Society. It consists of a gazetteer of all Teulon’s known new churches and church restorations, prefaced by an outline of his biography and a brief essay on his style. Though aspects of the presentation have a slightly homemade quality and the black and white illustrations could hardly do justice to Teulon’s colourful architecture (something acknowledged by the author), the scholarship is first-rate and the book very well written. This was followed by a general survey of his life and work included in The Architectural Outsiders, a collection of essays by a range of authors on neglected architects of the 17th to early 20th centuries, which appeared in 1985. Matthew Saunders also contributed all the entries on churches by S.S. Teulon in The Faber Guide to Victorian Churches, published in 1989.

Background and training

So there is a firm foundation, and it is thanks to Matthew that we know plenty about Teulon’s personal circumstances. The surname implies French heritage and his ancestors were Huguenots, just like Robert Lewis Roumieu. Teulon’s family was involved with the French Hospital originally known as La Providence, for which Roumieu designed new premises in south Hackney. Several members in past generations were directors, and both Samuel Sanders Teulon and his brother, William Milford Teulon (1823-1900), who also went into architecture, served as trustees. The family was comfortably circumstanced. One branch of it owned an estate at Limpsfield Common in Surrey, and Samuel’s parents resided at Hillside, a Georgian mansion in Greenwich on Crooms Hill – the exclusive and fashionable street which leads up from the centre of the town towards Blackheath. His father, also called Samuel, was a cabinet maker and upholsterer, who later on in life had turned to surveying.

Teulon began his training as a student of the drawing school at the Royal Academy. It was an auspicious time to study there, since both John Soane and J.M.W. Turner could conceivably have been among his teachers. Whether he came into contact with them and, if so, what influence they exerted remains to be discovered, but there is no doubt that Teulon was an artist of considerable ability, as shown by the sketchbooks now in the RIBA collection which illustrate his travels around Britain and continental Europe. The latter were conducted in 1841-1842 in the company of fellow-architect Ewan Christian (1814-1895), who became a lifelong friend.

Teulon acquired his grounding in construction and architecture from George Legg (1799-1882) and George Porter (c. 1796-1856). Little is currently known about the career of the former, other than that in 1844 he became district surveyor to Belgravia and Pimlico. The latter also practised the professions of both surveyor and architect. His office was in Bermondsey, where he laid out part of the West Estate, and in 1824 he became District Surveyor for Newington and North Lambeth. It seems that his professional practice also took in a measure of civil engineering, since in 1825 he had been engaged to widen the medieval Town Bridge over the River Wey in Guildford (destroyed by flooding in 1900). Insofar as can be judged from his few surviving works, he seems not to have been dogmatic about style, as was typically the case with architects of that generation. The front that he added in 1830 to the mother church of Bermondsey, St Mary Magdalen, is Georgian Gothick, while the buildings for the London Leather Company (at any rate, going by what has survived of the complex to the 21st century) were in a spare classical manner typical of much industrial architecture of the time. At the almshouses for the Watermen’s Company in Penge, built in 1840-1841, Porter employed the free Tudor Revival popular during that decade for institutional and public buildings.

As early as 1835, while presumably still a trainee in Porter’s office, Teulon had entered a design in a competition for a new town hall and market complex in Penzance, Cornwall. This had been produced jointly with Sampson Kempthorne (1809-1873), a fellow alumnus of the Royal Academy Schools who soon afterwards became architect to the Poor Law Commissioners and developed a line in workhouses. The same year Teulon married Harriet Bayne with whom he had six sons (two of whom died in infancy) and four daughters. In 1836, he produced a design for baths at Lee in southeast London and the following year a scheme for a county hall and law courts at Ipswich in Suffolk. Neither was realised, but by 1838 he was sufficiently confident of his ability to enter independent practice and executed his earliest known commission, the remodelling of Tensley Villa in Limpsfield, Surrey for Thomas Teulon (1764-1844). A view of the Penzance scheme was shown at the Royal Academy, as was his winning entry in a competition held in 1840 for new almshouses for the Dyers’ Company on the Balls Pond Road in Islington. This was a pretty Tudor Gothic design, still essentially Georgian in spirit (it was symmetrical and might just as easily have been decked out in classical detail) and gave few hints of what Teulon would go on to do. It had a certain kinship with the Watermen’s Almhouses, and indeed around this date Teulon was busy helping his former teacher with that commission. In 1846, he moved to an address on South End Green in Hampstead named Tinsleys, where he lived for the remainder of his life.

The start of independent practice

It is perhaps worth dwelling on Teulon’s architectural training, for although there is much to suggest that it was thoroughgoing and highly professional, there is nothing here which necessarily predisposed him to be the ecclesiastical specialist that he went on to become. He would conceivably have been equally well placed to carve out a niche for himself in residential or commercial work. Yet he went on to produce designs for 114 ecclesiastical commissions – new churches, remodellings and restorations, to say nothing of his numerous vicarages and church schools. The Teulon family was apparently strongly Evangelical in its churchmanship and it is clear, as will be touched on below, that the architect moved in circles that shared his sympathies. But this is an aspect of his life that requires more detailed study than it has hitherto received before one can begin to draw any conclusions about how it might have influenced the nature of his architecture. Goodhart-Rendel regarded Low Church Anglicanism as the milieu which promoted in the ecclesiastical sphere the idiosyncratic and wilful brand of revived Gothic of the 1850s and 1860s, whose practitioners he identified as ‘rogue architects’. He counted among them Enoch Bassett Keeling and Joseph Peacock. It is tempting to explain the highly individual nature of Teulon’s mature style as the result of employment by a clientèle for whom received notions of architectural propriety based on archaeological correctness were not an overriding concern.

In some cases the link would seem to be explicit, such as the extraordinary monument of 1866 to William Tyndale, translator of the Bible, commissioned by the second Earl of Ducie and raised on a splendid hilltop site at North Nibley in Gloucestershire. The roundels of Protestant reformers in the spandrels of the nave arcade at St Stephen’s, Rosslyn Hill also require little comment. But Teulon was nothing if not consistent, and while the implications of his architectural language may be clear enough in church design, when it is applied to country houses or model cottages, no such obvious conclusions invite themselves. All that can be said for the time being is that the thesis that architectural licence equates to Evangelical sympathies needs to be tested in each instance. Such sympathies were perhaps more in need of badges of allegiance than a thoroughgoing aesthetic and may ultimately be of more use in explaining how Teulon won his commissions than how they came to look as they did.

Teulon’s practice took a while to build up momentum and for the first 10 years or so he was busy with commissions for rectories and churches mainly in Suffolk, Norfolk and Lincolnshire. This period in his career has attracted comparatively little interest from architectural historians, but it is worth pulling out a few buildings to discuss briefly for what they reveal about his development. Wetheringsett Manor (formerly the rectory) of 1843, located in mid-Suffolk to the north of Stowmarket, is a large Tudor Gothic house in white brick with stone dressings, its garden front symmetrically composed. Winston Grange (formerly the vicarage), its exact contemporary located only a short distance to the southeast in the same county, is a different strain of the same breed – Tudor Gothic, only this time asymmetrically composed, constructed of red brick and with crow-stepped gables embodying a tradition of the locale in domestic architecture of the period that it emulates.

Teulon the church architect

At their simplest, Teulon’s new churches from this period are plain, lancet-style designs with little embellishment. More ambition is evident in buildings such as St Michael’s in East Torrington near Market Rasen (1848-1850), with its well detailed Decorated tracery and powerfully modelled west wall and bell cote, or St Mary’s in Riseholme, just to the north of Lincoln (1850), where the tracery is turning curvilinear and the patronage of Bishop John Kaye allowed for an interior of some sumptuousness. Or take St Peter’s, Great Birch in Essex of 1849-1850, the very image of a large, early Victorian church – a nave with two broad aisles, deep chancel and tower with a tall spire. All of the buildings examined so far are carefully designed, well detailed and imaginative, but they are of interest primarily as good period pieces. Most of what is here could easily have been cribbed from R.C. Carpenter or one of the other Puginian Goths. They do not yet embody the strongly individual architectural personality that made Teulon’s reputation.

It is difficult to reconcile the architect of these buildings with the image that Teulon established for himself with his later work. Exactly when his manner became wilful and acerbic is difficult to pinpoint, and it was probably a gradual process rather than a sudden change. That seems to have begun right at the end of the 1840s and to have been in full flood by the middle of the following decade. It is significant that it was around this date when Teulon began to be lambasted in The Ecclesiologist. Its anonymous reviewers acted as arbiters of architectural and liturgical rectitude, establishing canons of taste generally founded on the work of practitioners in the service of the High Church party that it represented. Teulon’s Evangelical sympathies have already been mentioned; many of his buildings were designed for Low Church worship rather than the revived ritual of the Middle Ages, and this alone would have been enough to raise the heckles of The Ecclesiologist’s reviewers. St Paul’s in Bermondsey, completed in 1848, drew flack for being fitted with galleries – it was essentially a preaching box. It was criticised also because only the tower and east end of the building, which fronted the main thoroughfare of Kipling Street, were finished in stone, the rest being plain stock brick, the kind of sham that was viewed as the currency of lapsarian Georgian architects

Yet the politics of churchmanship cannot wholly explain the lack of favour. Detailed research would be needed to corroborate such an interpretation, but one begins to get a sense from some of the comments that the problem ultimately was that Teulon’s work was perceived as tacky, vulgar and meretricious. The Ecclesiologist concluded about St Paul’s that there was ‘a pretence about the whole design which makes it far more repulsive to us than a church which is honestly cheap and bad’. Teulon’s proposal to remove the catslide roofs spanning both nave and aisles and to reinstate a clerestory in his restoration of the medieval church of All Saints, Icklesham in East Sussex of 1848-1849 seems to have been viewed as an attempted imposition of questionable taste: ‘We had not much opinion of Mr Teulon’s ability but we were not prepared to see him… so wantonly destroying a feature of extreme singularity and picturesque effect in an ancient church’. Christ Church, Croydon, completed in 1852, was dismissed as ‘mediocre’ (although as Matthew Saunders points out, the adjective was employed frequently and indiscriminately by the publication) and criticised for the mean planning of the apse and flimsy, slapdash detailing.

In two of the works named above, one sees the germs of Teulon’s mature style in his bold and licentious handling of motifs and devices ostensibly drawn from the architecture of the Middle Ages. At Icklesham, every other roof truss in the nave (the proposed clerestory was eventually omitted) is supported on wooden colonettes modelled like detached stone shafts – presumably a purely aesthetic mannerism, since the secondary trusses that alternate with them extend downward no further than the springing of the arch brace. All of them, however, rest on corbels with rich, deeply undercut foliate carving, which is employed too for the extraordinary font with overlapping trefoils wrapped around the bowl. The west porch is a highly picturesque hexagonal form. At Bermondsey, the east window was filled with spidery tracery, while a powerfully modelled polygonal stair turret was positioned at the junction of the chancel and bell tower, one of the corner buttresses running over its steeply pitched roof and down one of its faces – again, caprice was at play, rather than archaeological correctness or structural logic.

The Puginian style of the 1840s is pulled around, distorted, perverted and ultimately made into a parody of itself. Curvilinear tracery gets more intricate, sinewy and tangled; cusping gets larger or more acute; motifs are piled up, superimposed, collide with and puncture one another. Components which in the original would be subsidiary to the composition as a whole, such as stair turrets and transverse gables, take centre stage, while utilitarian features such as clock faces and boiler house chimneys become vehicles for invention and are treated as architectural statements in their own right. Everywhere the trend is towards complexity, even fiddliness, towards never using one word where ten will do. Ornament, especially architectural sculpture, is exaggerated and overscaled. At St John the Baptist, Netherfield in East Sussex of 1854-1855 the pot is simmering; at Holy Trinity, Hastings of 1857-1862, it is boiling over. The apotheosis of this manner is St John the Baptist, Huntley in Gloucestershire, a medieval church rebuilt in its entirety apart from the tower in 1862-1863, whose sumptuous interior is thoroughly baroque in its profusion of ornament and colour.

A little later, probably around 1855, Teulon began to absorb the Ruskinian style pioneered by architects such as G.E. Street, which combined the muscular forms of early French Gothic with features drawn from Italian architecture of the early Middle Ages, principally structural polychromy. But here again, it is viewed, as it were, in a distorting mirror. The forms are uncompromisingly thick-set, the modelling sometimes strikingly elemental, the stripes and diapers bolder and more vivid. Teulon grasps the potential of the style in a way that none of his contemporaries managed in buildings such as St John the Baptist, Burringham in Lincolnshire of 1856-1857, where buttresses, string courses, hood moulds and other projections from the wall surface are largely suppressed to achieve a powerfully modelled assemblage of near-prismatic forms. What appears to be a dumpy west tower turns out to be kind of ante-chamber to the nave, open inside to the roof structure and with a bizarre chimney perched on and clasping the northwest corner. It was a language of form that served him well in a number of commissions to recast Georgian churches in a High Victorian manner, most notably St Mary’s in Ealing, where, between 1864 and 1874, Teulon remodelled almost beyond recognition a plain building originally of 1735-1740 by James Horne.

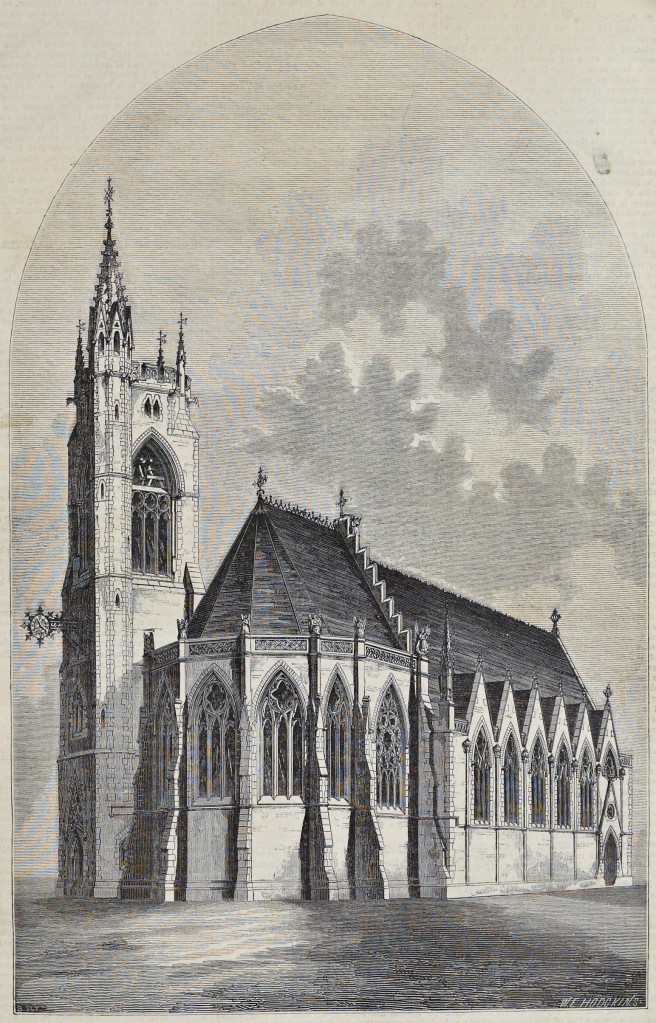

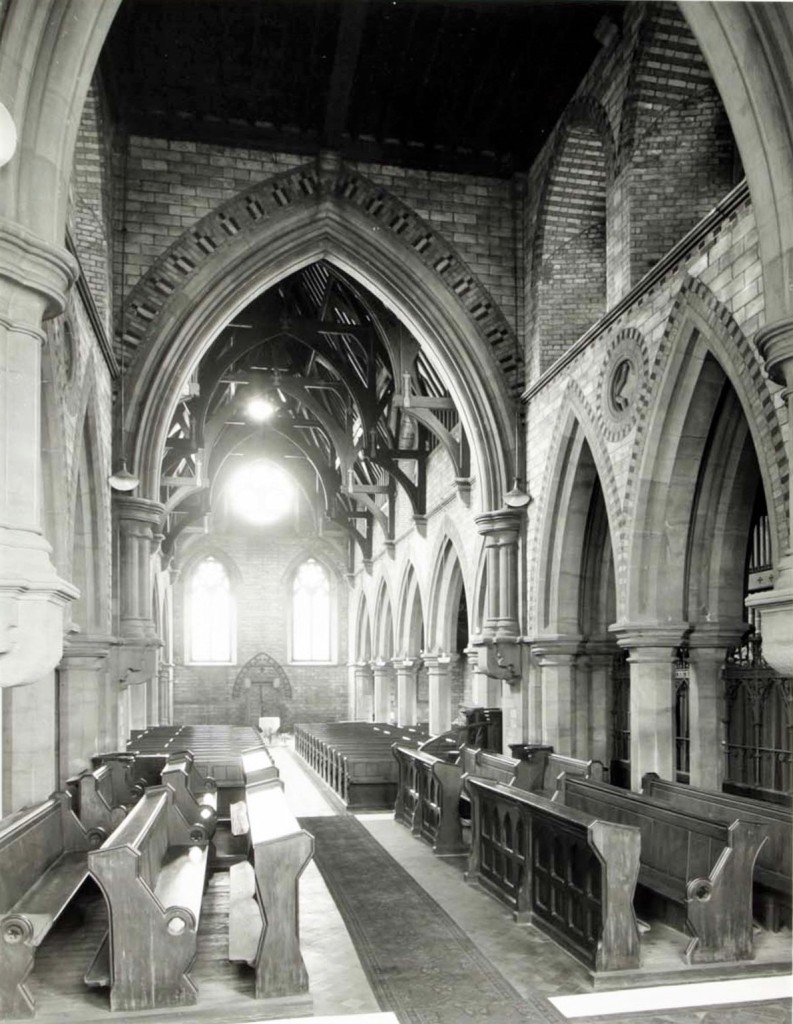

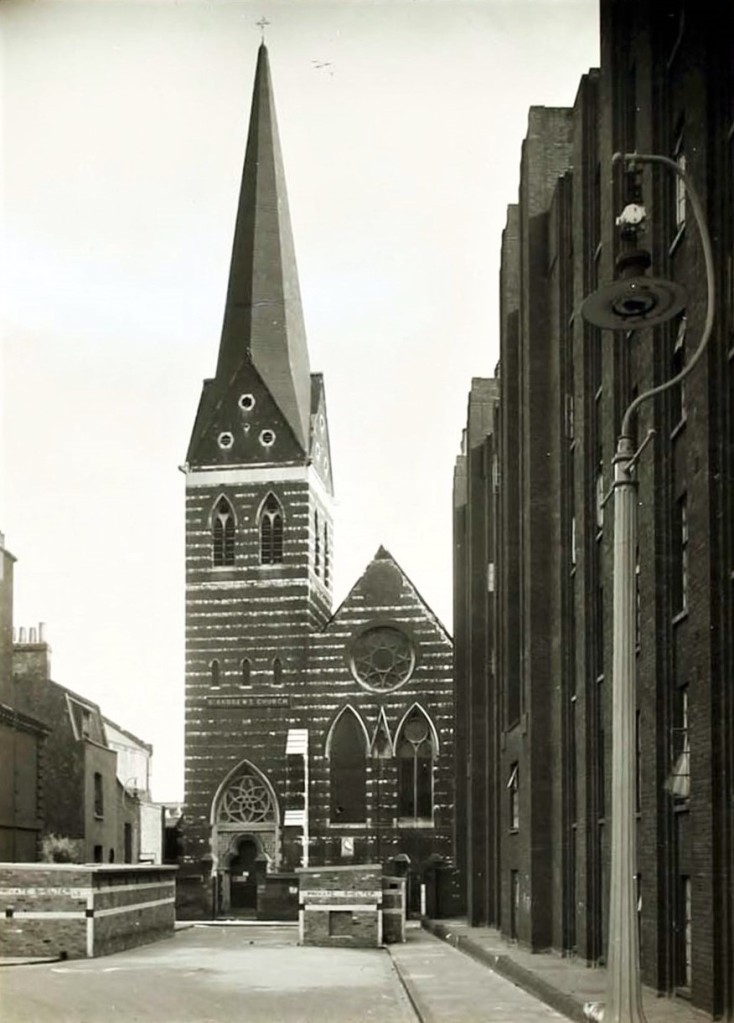

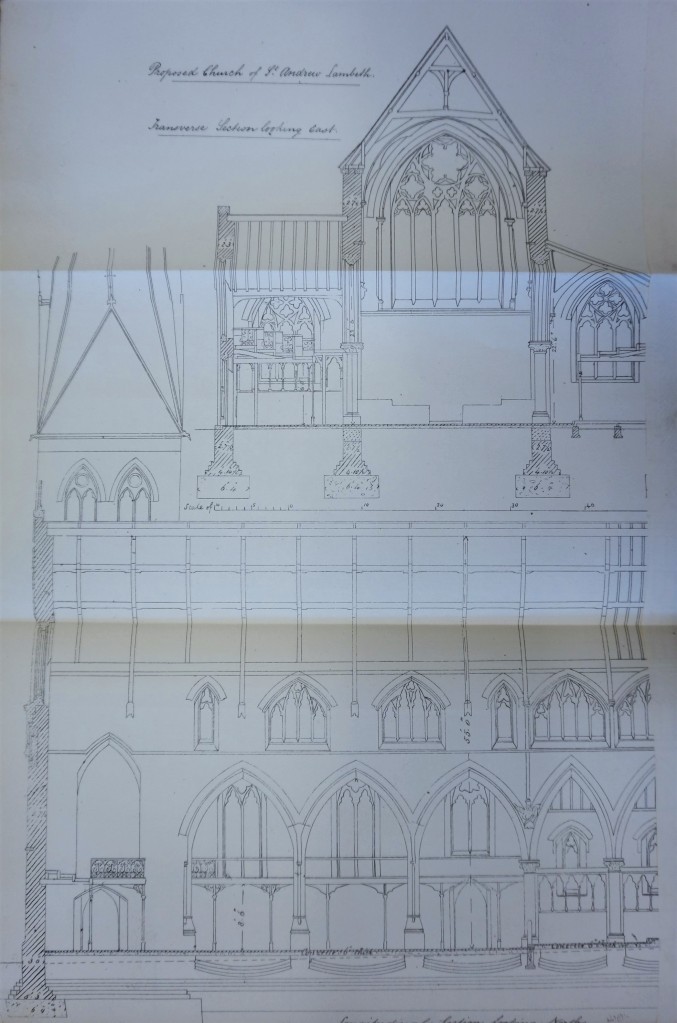

But Teulon was not merely highly inventive in his treatment of historicising motifs, he was also omnivorous in his sources. At St Andrew’s, Coin Street in Lambeth (designed 1854, consecrated 1856), he turned for inspiration to the Backsteingotik churches of the Hanseatic cities of northern Germany. This is particularly evident in the tower, which lacks any buttressing – as is the case with the prototypes – and where tall gables to each elevation of the belfry stage help effect the transition from square tower to octagonal spire. Teulon had first tried out a Rhenish helm spire at St Stephen’s, Manciple Street in Southwark of 1848 (demolished 1965): in most other respects, that was an unadventurous design, but when he used the device again 17 years later for the rebuilding of SS Peter and Paul, Hawkley in Hampshire, it formed part of a striking and convincing essay in neo-Romanesque with decidedly Germanic overtones. Perhaps he had been prompted by recollections of something that he had seen on his travels as a young man. It is likely that he had seen for himself Romanesque buildings in the Rhineland, and one of the sketchbooks in the RIBA Collection includes a view of Friedrich August Stüler’s SS Peter and Paul in Wannsee outside Berlin, a Rundbogenstil design completed in 1837. At St Mark’s, Silvertown (now the Brick Lane Music Hall) of 1860-1862, Teulon cast his net even wider, filling the belfry windows and those below lighting the chancel with square-section tracery in geometrical patterns that recall the openwork screens in Moorish architecture. Something similar, although interpreted even more personally, cropped up at St Thomas’s, Agar Town in Camden (1863, demolished c. 1960 following bomb damage). Islamic inspiration is evident again at St Stephen’s, Rosslyn Hill in Hampstead (1869-1873), where Teulon used horseshoe-shaped arches to carry the tower.

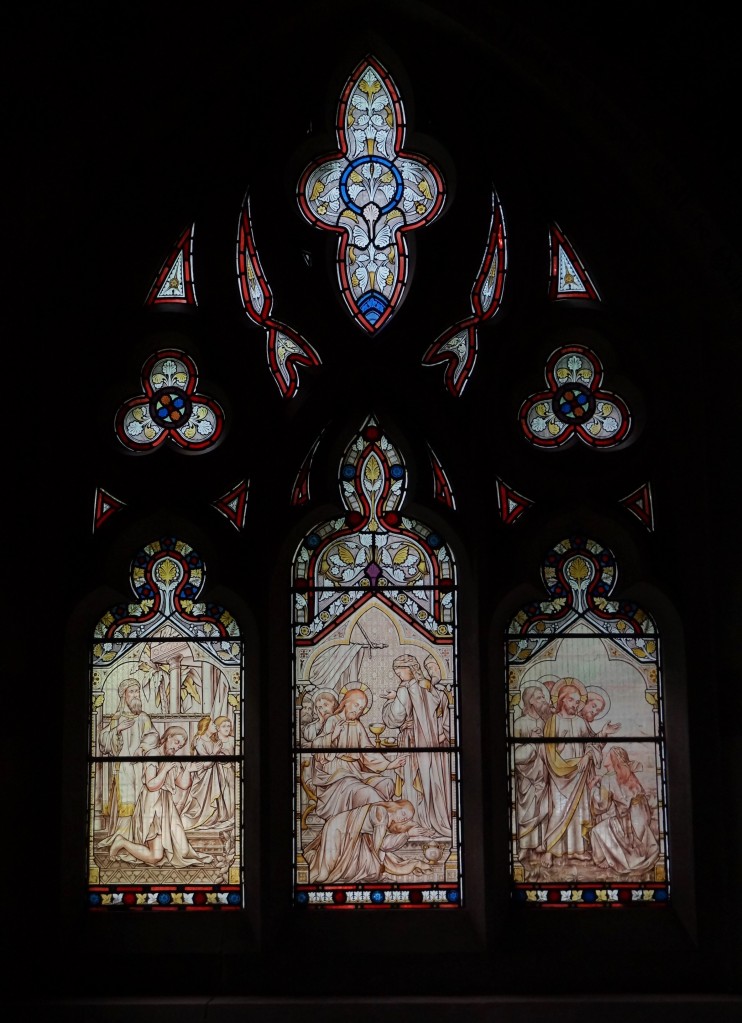

Teulon pursed a total aesthetic in his churches every bit as avidly as any other 19th century architect. Fittings were usually bespoke and their design is full of the invention and originality that characterise the architecture which forms their setting. He also collaborated extensively – and by no means exclusively on ecclesiastical commissions – with leading artists and craftsmen of the time: Thomas Earp (1828-1893) for sculpture (the reredos that he executed for St John the Baptist, Huntley was shown at the Great Exhibition of 1862), Clayton and Bell or Lavers and Barraud for stained glass, Skidmore of Coventry for ironwork and Salviati for mosaics. At Ealing, Huntley, Netherfield and St Thomas’s in Wells, he used unusual tinted glass with monochrome drawing supposedly of his own devising.

All of these commissions were generously supported by wealthy private donors. Yet Teulon was by no means dependent on largesse to stimulate his architectural imagination. Though The Ecclesiologist might have insinuated in its review of St Paul’s, Bermondsey that he regarded churches for poor areas as beneath his dignity, in his later career he showed himself able to make a virtue out of a necessity when designing a church on a tight budget. The point is made cogently by St James’s, Leckhampstead (1859-1860) on the Berkshire Downs outside Newbury, where savings were made on the execution of a most imaginative design through a number of ingenious expedients. What appear to be expensive vitrified bricks – an important element in a vividly polychromatic interior – are actually red bricks painted black. The mastic joints are in fact tuck pointing, also painted black. The cusped braces to the trusses at the east end of the nave have been assembled from several sections of planking, and much of the roof structure is held together with iron strapping rather than being jointed and pegged.

Teulon’s major country houses

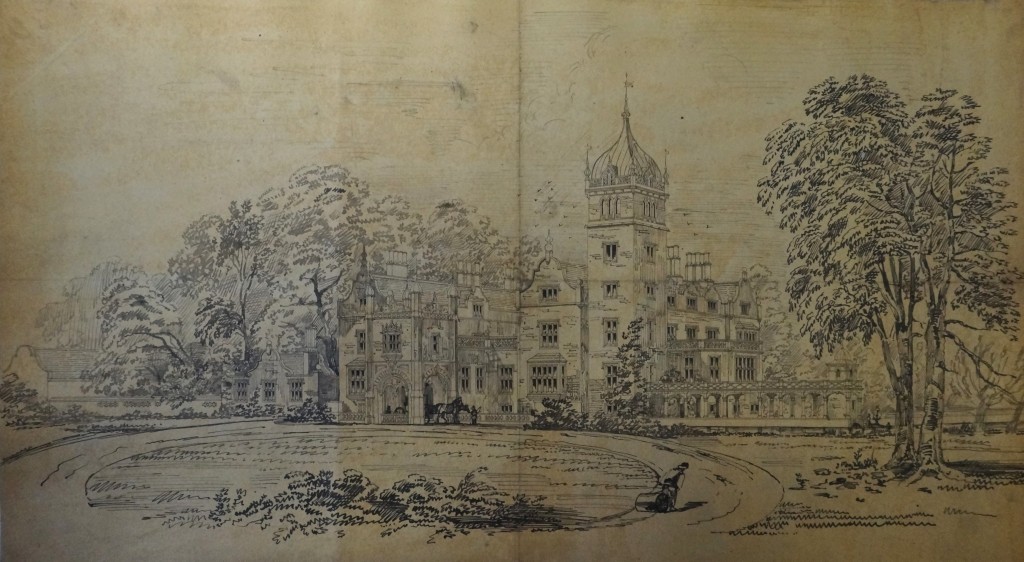

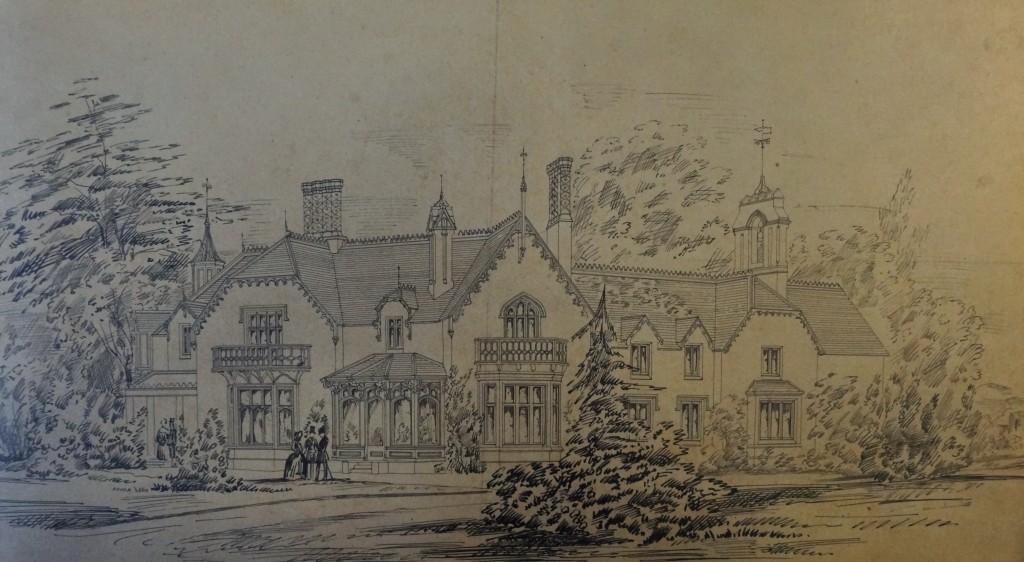

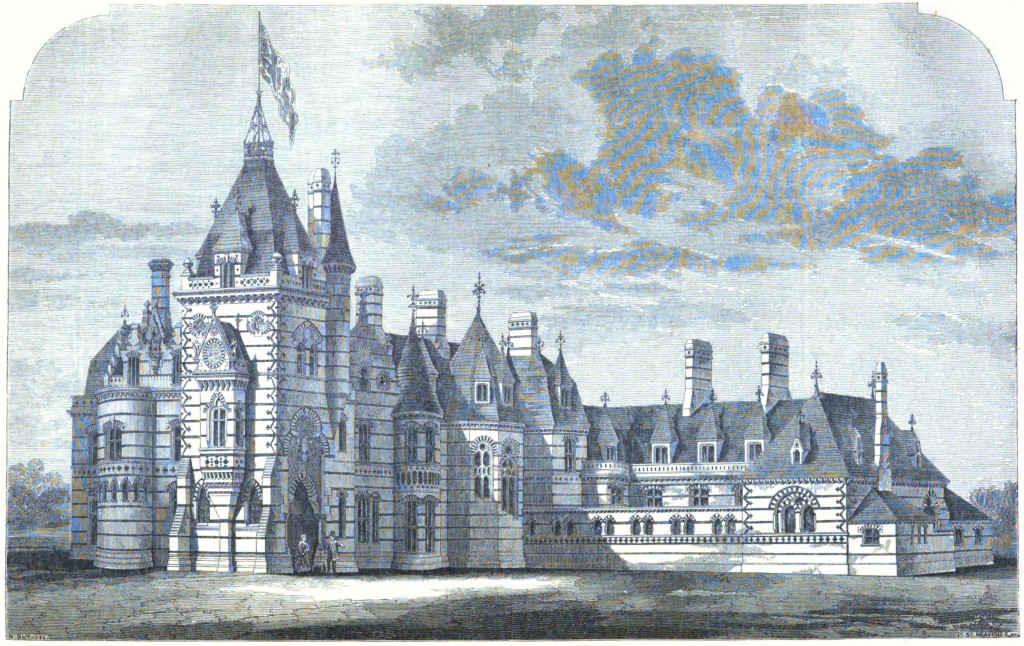

It is the churches that have made Teulon’s name. Yet he was also an important designer of country houses, which demonstrate his artistic development and embody his mature style every bit as vividly as any of his ecclesiastical commissions. The attention of architectural scholars has tended to be drawn by a quartet of major works. The earliest is Tortworth Court near Wotton-under-Edge in Gloucestershire, built for the second Earl of Ducie in 1849-1853 and Teulon’s first known large-scale venture in the field. It is the product of an architect – and, indeed, of an age – that had neither fully relinquished the fashions of a previous age nor wholly assimilated the innovations of the new one that was already upon them. A drawing in one of the sketchbooks in the RIBA Collection depicts an intriguing design for what is essentially an oversized cottage orné, based on a cranked axis, with a caption in a much later hand stating that it is Tortworth Court. If this was indeed Teulon’s initial offering to the Earl, then the concept evidently changed radically in the design process.

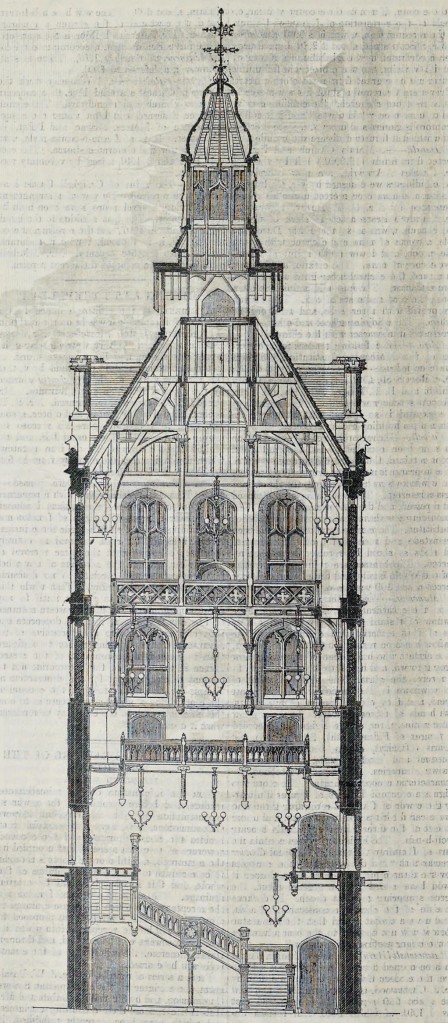

As built, the garden front is entirely symmetrical and effectively Georgian Gothick; the entrance front is wilfully asymmetrical, with advancing and receding planes, and decidedly Puginian. There is an uncomfortable discontinuity between the two and, as designed, it depended for its effect on a vivid skyline of turrets, gables, pinnacles and tall chimneys, all grouped around a tower containing the main stair with a tall pyramidal roof crowned by a large cupola (as Mark Girouard notes in The Victorian Country House, this feature owes a visible debt to James Wyatt’s Ashridge in Hertfordshire of 1808-1821). The removal of this feature in the late 19th century (around the time that the free-standing chapel was demolished and replaced by a conservatory) robbed the exterior of much of its coherence, while the subdivision of the grounds and later planting on the eastern side from which the house is approached (it is now a luxury hotel, with an open prison occupying part of the former park) has destroyed the long-range views in which it must once have cut an evocative figure.

Stylistically, the exterior is an amalgam of late Georgian Gothick, neo-Jacobean and Puginian Gothic. What can be deduced from the surviving interiors – much was apparently lost during a bad fire in 1991 – suggests that, within, the detailing was mostly Tudor Gothic, but there are germs of several ideas that recur in Teulon’s later work. The use of overscaled brackets to support the flights landings of the main styair, for instance, is an early instance of something that became a favourite device and was translated into his brand of muscular Gothic. The architectural language was flexible and, as had already been shown at houses such as Ashridge, could easily be adapted to suit plan forms and massing that owed little to medieval architecture. Nor did evoking the Middle Ages preclude technological advancements, and Tortworth was equipped with a hot air heating system, gas lighting and a system of carts running on rails and lifts to distribute coal around the house. It is perhaps telling that Marsten, a contemporary estate cottage on a road that skirts the eastern boundary of the parkland, coheres more successfully as a discrete sculptural form: Teulon had yet to develop an architectural language capable of responding to large-scale planning.

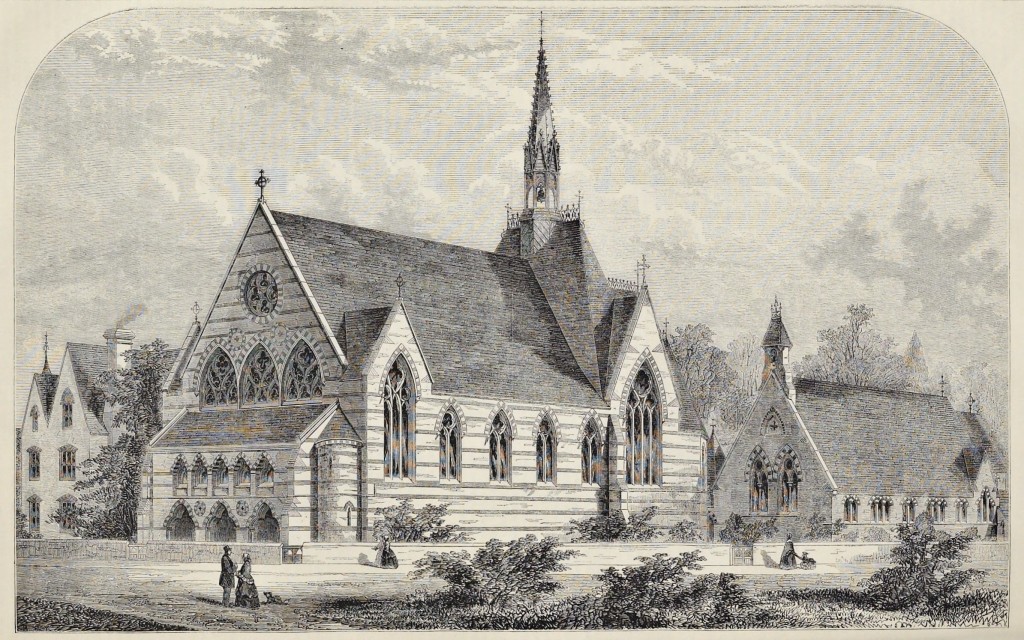

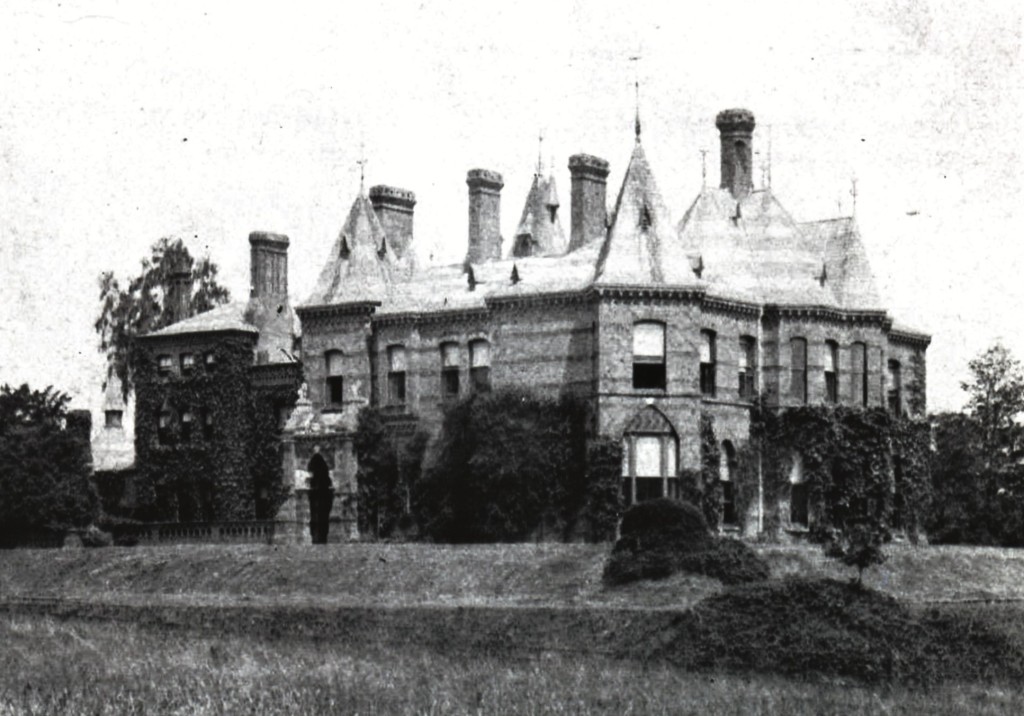

At Shadwell Court in Norfolk, Teulon remodelled and extended earlier fabric rather than designing a brand new house, but his work was so extensive that it nonetheless constitutes a major statement. The Buxton family was based at Channonz Hall, a large Elizabethan house at Tibenham near Diss. They apparently shared no more than a surname and roots in the east of England with the family of Thomas and Charles Buxton, discussed in my blog post on Foxwarren Park. In 1727-1729, they built a mansion on an estate not far away to the west as a summer retreat. It proved much better suited to living patterns of the time and they abandoned Channonz. But that, for all its drawbacks, was a more capacious property and they came to outgrow Shadwell. In 1840-1843, Edward Blore (1787-1879) was commissioned to enlarge the house by Sir John Jacob Buxton, who died while the work was in progress. After his son and heir, Sir Robert Buxton, came of age in 1850, he and his mother embarked on a major programme of building work. Teulon was engaged to rebuild and enlarge the parish church of St Andrew’s in Brettenham on the edge of the estate, which was done in 1852. In 1855, he was commissioned to rebuild as a rectory the medieval building at nearby Rushford that had formerly housed the canons of the originally collegiate parish church of St John the Evangelist. This was done, although a scheme to rebuild the church itself (much reduced after the dissolution of the college) remained on paper.

In 1855-1860, Teulon rebuilt Shadwell. The service court is entirely his, but work on the house itself consisted mainly of the extensive remodelling and raising by one storey of an office wing added by Blore, hollowing out of the centre a cruciform music room and adding on a large new dining room. These were, as Girouard put it, ‘the only Teulon interiors of importance at Shadwell’, but then client and architect seem to have been more preoccupied with the aim of creating as a centrepiece for the estate a vast, sprawling pile with a vivid skyline of spires, turrets, gables and steeply pitched roofs that would appear from a distance like a small city. A new entrance route was provided across the park from the west, which wound around the house on its final approach, affording dramatic, constantly changing views of this spectacular ensemble. Teulon’s addition of a thumping great tower over the main door might have thrown the entrance front off-centre; balance is restored by the intricately modelled clock tower over the gate to the service court with its octagonal upper stages, the adjacent stout, drum-like game larder and, beyond, the gatehouse in the centre of the stable block, with its crow-stepped gable and staircase tower with a candle-snuffer roof.

The style is Teulon’s almost hallucinogenic reinterpretation of Puginian Gothic with delight evident from every view in his excursions into complex geometrical forms and restless variations in outline and detail. Architectural sculpture, much of it by Earp, plays an important role. Though the flint flushwork pays lip service to local traditions, it is simply more grist to Teulon’s mill in creating exhilarating variations in texture, colour and material. The estate remains and is used as a stud farm for racehorses, owned until his recent death by Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum, but the house is now in poor condition after a lengthy period of neglect.

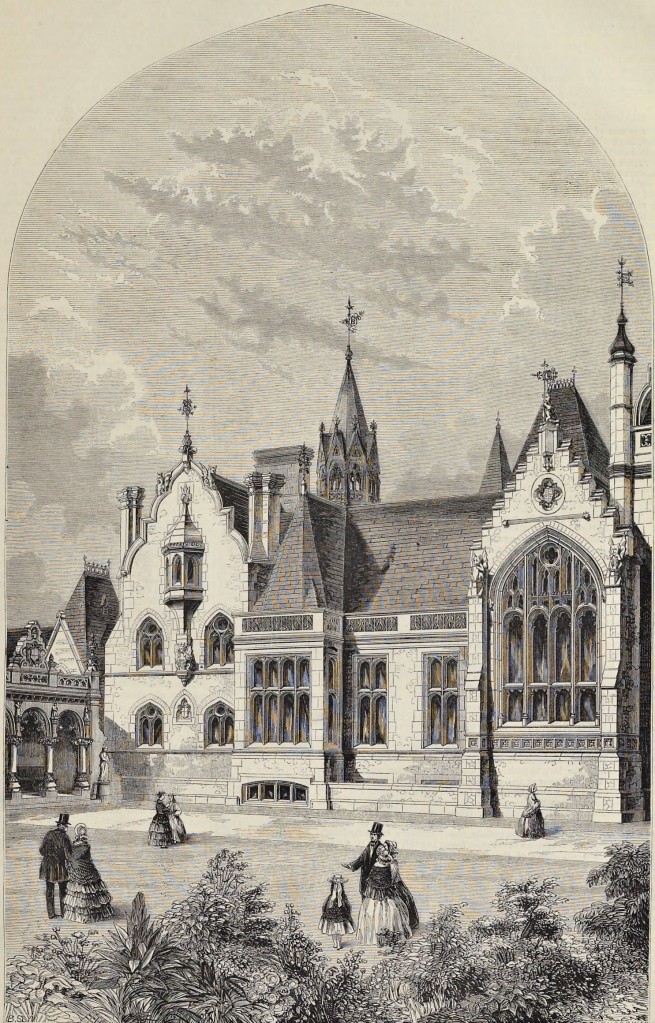

Work had begun on Elvetham Hall near Hartley Wintney in northeast Hampshire before Shadwell Court had been completed, but this building reveals a very different aspect of Teulon’s architectural personality. It owes much to the architectural language that seems to have come into being at St John the Baptist in Burringham, but there are few pointed arches to be seen. A curious kind of stretched trefoil with keystones at the intersections of the arcs forms a kind of leitmotif in the design. It is shrunk to the scale of an image niche, blown up and stretched laterally in its proportions to serve as arches to the service court, but always employed in a manner entirely detached from the architectural language of early Gothic whence it derives. It is used sparingly, mainly at visually prominent locations, and the remaining openings of windows and doorways are almost everywhere segmental. When tracery finally appears in the windows to the main stair, it takes forms reminiscent of 17th century ‘Gothic Survival’. Indeed, eclecticism is the keynote, in that a stylistically diverse variety of devices is thrown into the mix – square pinnacles and openwork parapets that might have been cribbed from Elizabethan architecture at its most mannered, Dutch gables, thoroughly classical moulded cornices and ball finials.

Yet Teulon’s omnivorous approach does not translate into stylistic indeterminacy since all these features are subsumed into a compelling, strongly individual whole. The boldly asymmetrical composition is modelled in powerful, chiselled forms, with stridently patterned polychromatic brickwork, produced in kilns set up on the estate, pullulating in each elevation. Whatever the historicising overtones may be, the aesthetic is distinctly and unmistakably High Victorian, capable of being ascribed to no century other than the nineteenth. It is sustained throughout all Teulon’s numerous buildings and structure on the estate, which include not only the mansion and stable block, but also a bridge across the River Hart, walls and steps in the pleasure grounds, estate housing and even a water tower. The church of St Mary a short distance away to the east in the grounds had been rebuilt in neo-Norman by Henry Roberts (1803-1876) in 1840-1841. Teulon’s brief here seems to have been confined to adding architectural sculpture to the spire, turning Roberts’ design into a haunting, even unsettling presence, adding to the vivid skyline of the ensemble. The interior of Elvetham Hall strikes a more light-hearted tone. Pageantry abounds in the extensive scheme of figurative art, executed in a variety of media, which celebrates events in the long and illustrious history of the house, notably the lavish reception put on for Elizabeth I and her retinue by the Earl of Hertford, the then-owner, in September 1591. The great hall incorporates an extraordinary apse-like alcove lit by tall lancets and glazed with Teulon’s distinctive monochrome stained glass, making it a secular counterpart to the baptistry at St Mary’s in Ealing.

Teulon had been engaged to work on Elvetham by Frederick Gough-Calthorpe (1790-1868) the 4th Lord Calthorpe, whose family owned the Edgbaston Estate. Starting in the late 18th century, they exploited the demand generated by Birmingham’s rapid expansion as an industrial and commercial centre by selling building leases for its development as a middle-class suburb. The family had acquired Elvetham through marriage in the 1700s, but leased the estate to a succession of occupiers from the end of the 18th century, when it ceased to reside there. In the 1800s, one of these – Lieutenant General Gwynne, a veteran of the Peninsula Wars – demolished a large, substantially Elizabethan house and replaced it with a relatively modest classical villa. The 4th Lord Calthorpe left Edgbaston to take up residence at Elvetham and it was income from the ground rents that allowed him to rebuild the house on such an imposing scale. The choice of architect seems to have fallen on Teulon because he had already commissioned from him a number of buildings for the Edgbaston Estate, notably the church of St James (1851-1852), as well as modifications to Perry Hall in Staffordshire, another Calthorpe property.

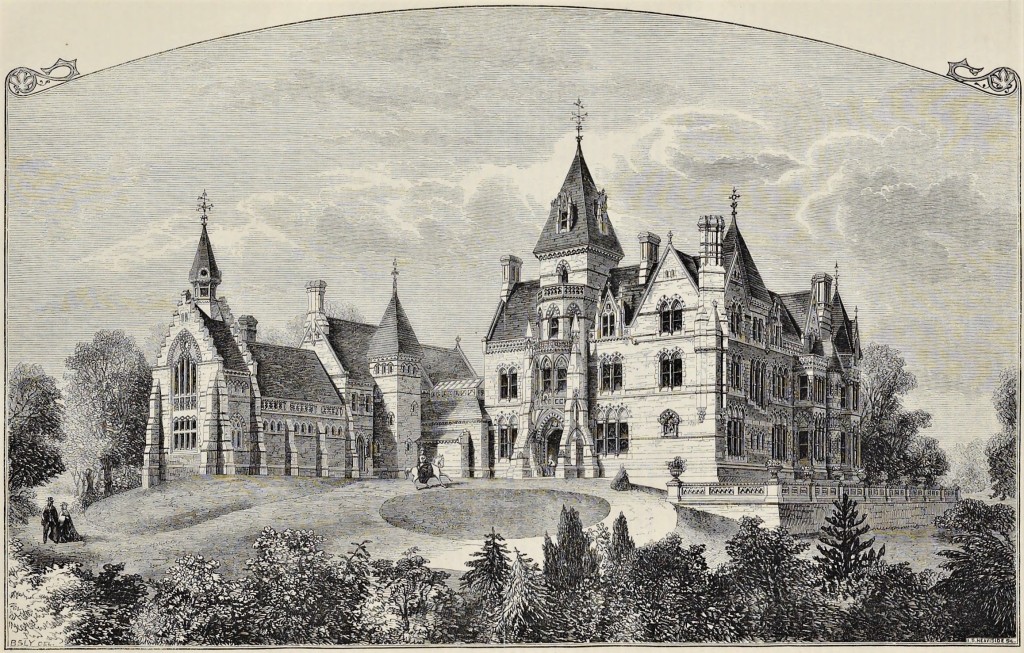

The circles in which the Calthorpes moved had an important bearing on Teulon’s career. There is a great deal to be discovered about how his entry to them came about and the succession of introductions that followed. The third Lord Calthorpe had been a close friend of, among others, William Wilberforce, Joseph John Gurney and Thomas Fowell Buxton, as well as being a staunch supporter of many of the national evangelical societies. The fifth lord was part of the Marlborough House set, which revolved around Edward, Prince of Wales. So also was the 10th Duke of St Albans, William Amelius Aubrey De Vere Beauclerk (1840-1898), who commissioned from Teulon Bestwood Lodge on the northern fringes of Nottingham, built in 1862-1865. Here, the strident manner of Elvetham is still present, but overt medievalising returns, this time in the form of the architect’s highly personal interpretation of Ruskinian Gothic. As at Shadwell Park, every possible device at Teulon’s disposal – steep gables, pyramidal roofs, towers and turrets of differing sizes, decorative ironwork, prominent chimney breasts and tall stacks – are brought into play to create an evocative skyline, whose effect is augmented by the substantial quadrangular stable yard to the north, for which similar devices are employed. The components of this sprawling complex are picturesquely disposed and the massing broken up in a manner that belies the substantial proportions of the house.

The servants’ hall that extends along the north side of the cour d’honneur is treated as a discrete form and terminates at one end in a tall crow-stepped gable and spired bell cote, giving it an ecclesiastical air that might lead a casual observer to mistake it for a domestic chapel – something noted, greatly to its displeasure, by The Ecclesiologist. Even allowing for the impact of later alterations, the eschewal of symmetry in the elevations and axiality in the composition is the defining feature of views from any angle, making a perambulation of the grounds a decidedly disorientating experience, something accentuated by the sharp fall of the land on the garden side. The love of sculptural invention is again evident, especially in the hyperactively busy composition of the entrance tower with its intricate buttressing and oriels. The house originated as a hunting lodge in a royal park, which had reputedly been granted by Charles II to Nell Gwynn, his mistress and mother of the 1st Duke. As at Elvetham Hall, episodes from the past history of the site and local legend informed the decorative scheme, the sculptural elements of which were once again executed by Thomas Earp, this time in red Mansfield stone. The base of the oriel window above the main entrance incorporates portrait busts of Robin Hood and his Merry Men, while a relief in the Great Hall depicts Edward III hunting in Bestwood Park.

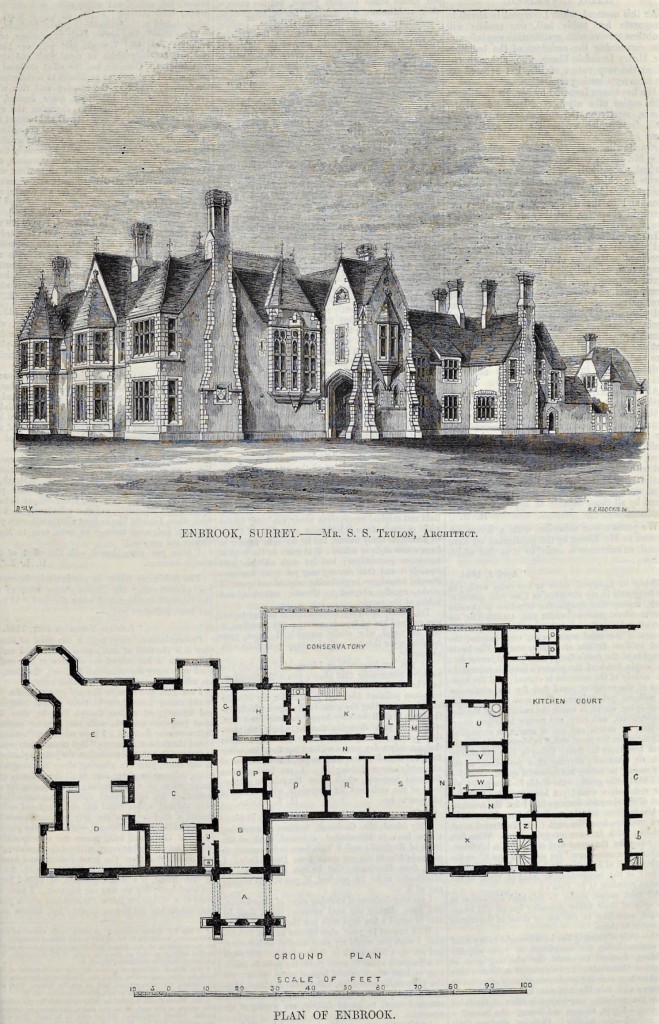

Tortworth, Shadwell, Elvetham and Bestwood constitute an impressive achievement by any standards of the 19th century. There is a great deal to ponder here, not least the fact that, having been commissioned by ‘old money’, all these works call into question the paradigm of a grandiloquent kind of revived Gothic as the preferred style of the Victorian nouveaux riches who had been elevated in station by the industrial growth of the period. But these four houses by no means exhaust the record. Enbrook in Sandgate near Folkestone in Kent, built for the sixth Earl of Darnley (1853-1855, demolished) was an impressive house in an earnest Puginian manner, although already going roguish in touches such as the window lighting the main staircase. Woodlands Vale between Ryde and Bembridge on the Isle of Wight of 1870-1871 was commissioned by the fifth Lord Calthorpe – not as a country seat, but as a summer coastal residence, and was not a brand new house, but a remodelling of an 1840s villa. The French Renaissance manner is idiosyncratically interpreted, and does not immediately suggest the hand of the architect.

Smaller country houses, other residential work and estate buildings

Elsewhere, Teulon’s country house practice brought commissions for extensions and modifications to existing buildings in addition to the construction of entirely new ones. Some may have been minor, but others, though subsidiary to the host building, are still wholly characteristic statements of his work, such as the service wing added to Warlies Park (another Buxton property) in Upshire near Waltham Abbey in Essex. This is dated to 1879 in several reference sources – erroneously, since the architect was long dead by that point – and here, as in so many other places, there is ground to be broken in researching this aspect of Teulon’s career. Country houses are particularly susceptible to the vagaries of fashion, seldom more so than during the 20th century reaction against High Victorianism, which often led to dramatic recastings and the obliteration of entire phases in a building’s architectural evolution. Such a fate befell Hawkley Hurst, which had been built for J.J. Maberly outside the village to which this landowner gifted the neo-Romanesque church pictured and described above. Following its sale to a new owner in 1912, the house was rebuilt out of all recognition and the towerlet with a candle snuffer roof attached to what must have originally been a service wing is the only feature of the Cotswold Elizabethan pile now occupying the site that is recognisable from the illustration reproduced below. Access to country houses can be difficult to obtain for field study, while papers vital for an architectural historian’s research sometimes have yet to be deposited in record offices or may have disappeared altogether, further complicating the task.

It was rare for architects with a country house practice not to be called upon to design estate buildings and Teulon’s work in this field constitutes a major part of his output. Around ten years after he commenced independent practice, he landed a commission to design houses for the ninth Duke of Bedford at Thorney in Cambridgeshire. Surviving correspondence with the Duke suggests that Teulon was already familiar with ideas on sanitation being promoted at that date by the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes, mentioned previously in my post on Henry Darbishire. His involvement with the Society may have brought about an introduction to Prince Albert, who took an interest in its activity, and this, in turn, could have led to commissions for the Royal Estate in Windsor. In addition to workshop buildings (1858) and the addition of a chancel to Queen Victoria’s chapel at the Royal Lodge (1863), Teulon supposedly extended Prince Consort Cottages on Alexandra Road in Windsor itself. This is a complex of model housing of 1855 built to designs by Henry Roberts, who had been much involved with putting into practice the ideas advocated by the Society. In the same year of 1855, Teulon built Crown Cottages near Queen Anne’s Gate to Windsor Great Park on the southern edge of the town.

The work at Thorney, which included a workshop for the estate incorporating a tall water tower, was in a free neo-Tudor manner familiar from some of his vicarages designed during the same period. By contrast, Crown Cottages are fiercely High Victorian, constructed of bricks laid in rat trap bond with liberal use of black glazed bricks to create striping and other polychromatic effects, as well as emphatic buttresses and chimney breasts. At Hunstanworth, a remote moorland village in the Derwent Valley of County Durham, Teulon was engaged around 1862 by the Rev’d Daniel Capper, the local landowner, not only to rebuild the church, but also to provide housing for local residents. Capper’s extensive landholdings included properties in Herefordshire and Gloucestershire, among them the estate at Huntley, where Teulon was at work rebuilding the church of St John the Baptist and Capper’s own residence of Huntley Manor at exactly the same date. Decent but plain housing to a standard design might well have been thought sufficient, as was the case on so many large estates. Instead, as Matthew Saunders notes, ‘All the cottages are of different design united only by the use of the same sort of stone and slate’.

It is becoming increasingly clear that a great deal has yet to be discovered about Teulon’s domestic architecture, especially the smaller country and suburban houses and estate cottages. Tintoch House (now Luxmoore) of 1860 on New Dover Road in Canterbury is noted but goes unattributed in The Buildings of England, and it also escaped the attention of Historic England’s listing inspectors, a circumstance which may explain the loss of the original interiors. Almost opposite is what was formerly Westfield House, a suburban mansion of 1860-1861 which, by contrast, is given an attribution in The Buildings of England, but also remains unlisted. By contrast, the attribution to Teulon of the remodelling of a modest 18th century cottage to turn it into what became Hawkley Place in the list description for that building may well be inaccurate. The date of 1862 in the same source is not borne out by map evidence and it is more likely that the work was carried out in the 1880s when Maberly purchased the property for his nephew.

But for the most part, the catalogue of Teulon’s works wants additions rather than subtractions. Although research is needed to corroborate the hypothesis, it would seem that his activity at Rushford in Norfolk for the Buxtons went beyond the remodelling of the former priests’ college. In addition to the school pictured below, there are two pairs of semi-detached cottages in close vicinity to it which appear to be of the same vintage and may well also turn out to be his work. The full extent of Teulon’s work in Upshire also wants clarification and description. He designed a combined chapel and school in the village (built c. 1855, demolished 1954) and possibly also the lodge by the entrance to the Warlies estate on Horseshoe Hill, which, with features such as dummy half-timbering, is characteristic of the picturesque manner that he employed for estate housing elsewhere.

Final years and afterword

That Teulon could have been busy simultaneously in Gloucestershire and County Durham gives some sense of the punishing workload that he handled for much of his life. At a time when many architects derived much of their income from surveying – a less laborious and more reliably remunerated line of business – he seems to have earned his almost exclusively through designing buildings. He bequeathed to posterity a rich, fascinating and most rewarding architectural legacy, but paid dearly for doing so. When he died in 1873 aged just 62, The Architect reported in its obituary that ‘there is no doubt that overwork had to some extent told on his constitution’. He was laid to rest at Highgate Cemetery. Though in later life Teulon did not want for extra hands in his office, reputedly he was reluctant ever to delegate. He was clubbable, attending Committee meetings of the Ecclesiological Society and serving on the RIBA Council between 1861 and 1865. But though he apparently took a close interest in the critical reception of his own work, he never responded in print and left no writings other than professional correspondence.

Though Teulon took pupils, none – as far as is currently known – went on to achieve anything of note. The line of development that he represented ceased with him. For this – and, indeed, for so much else – he would merit being grouped among the High Victorian representatives of Goodhart-Rendel’s rogues. But of him there is not a word in the lecture of 1949 which established that canon, and whether Teulon’s achievement is better understood by drawing parallels with the work of Roumieu, Peacock and Keeling is a moot point, which only a better understanding of his output and the context from which it emerged could settle. At any rate, four years later in English Architecture since the Regency, An Interpretation, Goodhart-Rendel wrote appreciatively of Teulon, calling him ‘the fiercest, ablest and most temerarious of [the] Gothic adventurers’, who had ‘a large and exciting practice’ and carried ‘modernism tumultuously across the border of caricature’. By ‘adventurers’, he meant the architects who, as the Gothic Revival wore on, were no longer content for their design to be circumscribed by a limited repertoire of forms hallowed by archaeological precedent and established good taste, and were thus driven to innovate. But then such architects by their very nature tended to be inimitable.

At a conference in 2018, I got into conversation with Matthew Saunders. It had long been rumoured that, on stepping down from the Ancient Monuments Society and the Friends of Friendless Churches, he intended to embark on a monograph on Teulon. By that point, he was almost a year into his retirement. I asked whether he had made a start and, if so, how he was finding the task. To my surprise, he responded that he hadn’t and thought it unlikely that he ever would. And then he asked, ‘But would you like to have a go?’ Of course, the answer was an unequivocal ‘Yes!’ Since then, he has been sending my way Teuloniana of all kinds, from old newspaper cuttings to Master’s dissertations. Chronicling and analysing the career of a workaholic architect is a daunting prospect and I can expect the task to keep me busy for many years, perhaps even decades.

Though it may in time serve as a good basis for a book proposal, this post can do no more than give a brief outline of what Teulon was about and identify some of the lines of inquiry that have yet to be pursued. But what makes the case for a monograph far more cogently than the promise of filling lacunae is demonstrating – as I hope the illustrations here do – the sheer visual enjoyment to be had from this colourful, exuberant, original, entertaining, ceaselessly inventive architecture, which begs to be made known to a wider public. The description of St Mary’s, Ealing in Nairn’s London sent me straight out there as a teenager to see the building for myself: ‘The inside defies description. It could be an agricultural hall, with cast-iron columns. It could be a nineteenth century copy of Cordova, with all the striped horseshoe arches. There are fish all around the bottom of the pulpit, and the horseshoe-shaped baptistry opposite is a complete space in itself, electrified with Teulon’s astonishing life force. Who? What? How? A rag-bag with enough ideas for a dozen churches: and a splendid place for a boggle’. My hope is that, book or no book, this post will have a similar effect on you.

1. Many thanks for all your work on this series. I was first alerted to it by the Ecclesiological Society newsletter abd have downloaded and printed the whole thing!

2. On Teulon, have you seen ‘Victorian Thorney’ by A E Teulon? It’s not particularly academic, but ineresting nonetheless.

LikeLike

Dear Edmund, I live in the Old Rectory, Binsted (BN18 0LL) which has recently been discovered to have been designed by S.S.Teulon. I’d like to correspond if this could be useful to you. Have applied for listing. Emma Tristram

LikeLike

Delighted to hear from you! Funnily enough, I was contacted a few weeks ago by Michael Bellamy of the Designations department at Historic England to ask if I knew anything about your house. I didn’t, but said I would be very interested to learn more, so please do tell me about the building as all I know at the moment is what little I can make out from Google Earth.

LikeLike

The Rectory was built in c.1863 (but possibly more like 1865) for Henry Christopher Bones, Rector of Binsted. (He changed his name to Lewis.) It is a quirky combination of Gothic and ‘Old English’ with stained glass, some pointed windows and door, polychrome brickwork and tile hanging. Michael Bellamy told me about ‘rogue’ Victorian architects and said the Rectory is ‘not quite Rogue, but getting there’. Lewis also paid for the restoration of St Mary’s, Binsted by Thomas Graham Jackson. Jackson’s work is so good that it helped me to get the church’s listing raised from Grade II to Grade II*. Would you like to email me and I can send you photographs?

LikeLike

Now there’s a name to conjure with! Jackson was also a wonderful architect. Yes, do please send photographs – drop me a line through the ‘contact’ section of the blog so that I have your address and I can then reply with mine.

LikeLike

I did leave my email in my first reply but here it is again.

LikeLike

Dear Edmund Do you have a copy of my book The life and work of Samuel Sanders Teulon Victorian Architect? I would be pleased to send you a copy. Alan Teulon

LikeLike

That’s very kind of you, but I think I still have one somewhere at home from when I reviewed it for ‘The Victorian’ back in 2011!

LikeLike