The three series of Six English Towns that Alec Clifton-Taylor made for the BBC in the 1970s-1980s are an excellent introduction to some of the most attractive, best preserved and architecturally most rewarding historic places in the country. All 18 subjects were well chosen and all of them will repay handsomely the time and effort of a day trip. For a while I was under the misapprehension that Faversham was among them. It was not – the only town in Kent to be included was Sandwich. But I aver that I was not wholly misguided in thinking that it might have been, since Clifton-Taylor would have found a great deal to enjoy there, principally the huge variety of vernacular buildings and traditional construction techniques, Georgian townhouses, well-preserved streetscapes and engaging topography in which he typically delighted. But, as someone whose antipathy for Victorian architecture was well known, there is also something which would have greatly displeased him, and it is this.

If one heads out of the medieval centre to the south or west, the townscape changes dramatically. Half-timbering, limewash, cladding in mathematical tiles, weatherboarding, stucco and peg tile roofs are replaced by stock brick, terracotta, slate and cast iron. Houses on main streets gain an extra storey. The haphazard, irregular medieval street pattern gives way to a strictly orthogonal layout. It is as though one had suddenly been spirited to a London suburb. And then one chances upon a most extraordinary apparition. A steeply pointed roof and twin, pencil-like turrets have been playing hide-and-seek in views from afar for some time now. But when one emerges onto South Road, one is struck not merely by the assertiveness of these features, but the sheer scale of the building to which they are attached. The chapel of which they form a part is merely the centrepiece of an immense frontage which stretches out in both directions to attain a length of nearly 500ft (152m). It would be striking enough in a big city, to say nothing of a market town. What is it and who designed it? One immediately suspects a neglected masterpiece by a major figure. But it is not.

Henry Wreight’s bequest and how the almshouses came to be

Almshouses are a prominent feature of many historic urban centres in Britain, and the building type has a long and illustrious history. Before the advent of the Welfare State, they fulfilled a vital role in providing for the poor and infirm in their old age. Like any town of comparable antiquity and substance, Faversham – a limb of the Cinque Ports and location of a major abbey until the Dissolution of the Monasteries – had several. How they came to be superseded by the edifice described above is an intriguing story recounted in The Building of the New Almshouses in Faversham by John Blackford, a booklet published in 2013 to mark the 150th anniversary of its opening, from which most of the information that follows is drawn. It begins with Henry Wreight (1760-1840), a successful and wealthy local solicitor, who founded two new sets of almshouses – one for six poor widows on Preston Street, and another for former dredgers or their widows on Abbey Street. By the time of his death, Wreight, who never married and had no dependants other than a widowed sister, had amassed a considerable fortune. He bequeathed to the town the bulk of his estate – valued at £80,000, an astronomical sum for the period – intending it to be used for good works.

A board of trustees to administer the town’s various charities had been set up four years prior to Wreight’s death and there was no shortage of deserving causes. But the terms of the will were vague and this left the trustees in a quandary as to how to put such munificence to a worthy use. Initially they proposed to rebuild and endow the town’s National Schools. This was agreed by the Charity Commissioners, whom they approached for guidance on the administration of the legacy. In turn, the Commissioners encouraged the trustees to apply to the Attorney General for a scheme to set out their objectives, which was eventually formalised by an Order in Chancery in 1856. Various proposals were entertained involving the improvement and expansion of the existing almshouses in the town before at some point in 1854/1855 they settled on the notion of uniting them all into a single institution, for which they would build new premises. To this end, they initially approached the architect Richard Charles Hussey (1802-1887). Born in Harbledown just outside Canterbury, Hussey initially trained with John Wallen (1785-1865), just like T.E. Knightley.

But the main influence on his professional development was Thomas Rickman (1776-1841), an important pioneer of the Gothic Revival, whose Birmingham-based office he joined in 1831. Rickman not only designed some of the first churches in which an archaeologically correct revival of medieval architecture was seriously attempted, but was also an antiquarian and scholar, who, in An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English Architecture of 1817, had set out the terms describing the main phases of English gothic – Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular – still in use today. Hussey became a partner in the firm in 1835 and took over as principal in 1838 when Rickman’s health began to fail. He practised extensively in his native county, undertaking numerous restorations of medieval churches, and was the architect of the new building of the National Schools in Faversham, completed in 1852 – an unusually lavish and grandly-scaled example of the type, planned like a collegiate complex with a tall gatehouse tower and inner quadrangle. The brief that he was handed by the trustees envisaged not just almshouses comprising 30 dwellings with their own chapel, but also a commercial school, library and a reading room.

Satisfied that the trustees were making good progress with the educational components of their scheme (which included not only capital works, but also funds to provide clothing for former pupils of the town’s national schools and exhibitions for study at Oxford or Cambridge for former pupils of its grammar school), in 1858 the Court of Chancery granted them permission to proceed with their plan for the new almshouses. Hussey’s design was adopted and submitted for approval to the then-attorney general, Sir Richard Bethell. At this point, events took an unexpected turn. In a letter of August 1859, Bethell castigated the design in the most virulent terms. ‘Everything is wrong. The site seems bad, the position of the Chapel which is so far from some of the houses, and the general idea… The sum to be expended is too large… instead of separate houses there should be one or two large houses built in flats and connected to the Chapel by a corridor’. As if this were not enough, the proposed library attracted little support from the townsfolk, who wanted a recreation ground instead. The trustees requested permission from Bethell to use part of Wreight’s legacy to purchase farmland on the east side of the town, but this was refused. The proposal could not be enacted until the following year when a local landowner, who in the meantime had purchased the land to build housing next to the new railway station, offered part of it for sale at a much reduced price and a portion of the cost was offset by a campaign of public subscription. The recreation ground was ceremonially opened in August 1860, but the library project fell by the wayside.

Supported by the Master of the Rolls, Bethell had insisted that Hussey should discard his existing scheme for the almhouses and prepare a new design. Instead, the trustees decided to open the field to new entrants and to hold a competition. The brief for the scheme was based on Bethell’s stipulations: the almhouses, all of which were to have a sitting room, a kitchen, two bedrooms and necessary outbuildings, should be linked by a covered way to a chapel in the centre of the complex. The site chosen for the complex was in the angle of Ospringe Road (later renamed South Road) and Tanners’ Street, and as many of the houses as possible were to have a frontage to one of these roads. The total cost was not to exceed £11,000 and the closing date for entries was 31st May 1860. George Gilbert Scott, who at the time was engaged in a major scheme of works to remodel and refurnish the town’s enormous parish church of St Mary of Charity, was invited to act as judge, but declined the offer because of pressure of work and suggested instead approaching Benjamin Ferrey, Philip Hardwick Junior and John Loughborough Pearson. The trustees settled on Ferrey, who undertook a ‘blind’ assessment and drew up a shortlist of four designs from which they were to select a winner.

Enter Wheeler and Hooker

Their choice, with which Ferrey concurred, had been entered under the initials ‘W.H’. These were not the initials of an individual, but the first letters of the surnames of Robert Wheeler (1830-1902) and John Marshall Hooker (1829-1906), two architects who had formed a partnership only the previous year. Hooker had been born into a landowning family in Brenchley near Tunbridge Wells. Nothing is currently known of his training, but from 1853 to 1857 he was in partnership with an obscure architect based in Margate by the name of William Caveler (dates unknown), who in 1835 had published Select Specimens of Gothic Architecture. Hooker’s earliest work so far identified is the rectory in Manton, a small village in the north of Lincolnshire to the southeast of Scunthorpe. He was back on more familiar turf in 1859, when he was engaged to design the combined gardener’s lodge and pavilion for the new recreation ground in Faversham. The banding of red bricks and striped voussoirs to the arches imply a passing familiarity with Ruskinian influence, but otherwise this is a charming exercise in the early Victorian cottage orné mode, full of self-consciously picturesque devices such as the acutely pitched roofs, the overscaled bargeboards and central oriel window. The tile-hanging is a recent addition – the first floor was originally finished in dummy half-timbering. In 1860, Hooker designed in a similar vein (apparently a solo effort, despite the partnership with Wheeler) a school on Churchfields in Hertford. This was established by Abel Smith (1788-1859), the banker and sometime MP for Hertfordshire, to take the girls from the Cowper School in the town, which had been established in 1841 and was now oversubscribed. The layout follows a well established pattern in consisting of a couple of large schoolrooms, arranged in a ‘T’ shape, with the schoolmaster’s house adjoining one end of the larger of the two.

Beyond the scant biographical details that can be extracted from censuses, Wheeler’s background and training still await elucidation. A native of Worcester, by 1856 he had an independent practice in London and apparently participated in competitions for a number of municipal cemeteries. That same year, he was engaged to design a new parish cemetery for Brighton, a measure made necessary in 1853 when the Privy Council prohibited burials in or around the churches and chapels in the town under the Burials Beyond the Metropolis Act. Wheeler’s mortuary chapels (adapted as a crematorium in 1930) embody a confidently handled robust kind of Geometrical Decorated Gothic, rather in the manner of R.C. Carpenter. The building follows the typical configuration of the period in consisting of separate chapels for nonconformists and Anglicans, arranged in a symmetrical composition with a bell tower and spire rising over what was originally a carriage arch for hearses in the centre. Lodges flanking the head of the drive from Lewes Road survive, although the ceremonial archway that formerly linked then, built as a memorial to the Marquess of Bristol, was demolished in 1947. Only one building other than the Faversham Almshouses has been positively identified as a joint work and that is the church of St Hybald’s in Manton of 1861, where Hooker had built the new rectory seven years previously. It is a typical High Victorian smaller rural church in Middle Pointed with a diminutive tower and spire over the porch to give it extra presence in the landscape – all wholly characteristic of the period but not embodying an especially distinctive architectural personality.

The same could not be said of the almshouses. The terms of the trustees’ scheme and the prescriptions of the Attorney General had a considerable bearing on the design. The basic configuration of a chapel positioned in the centre and flanked by terraces of two-storey cottages was well established for almshouses and examples are legion. What is surprising here is the greatly increased scale. In addition to the total of 28 dwellings provided by the five old complexes, the opportunity was taken to use part of Wreight’s legacy to create two more beneficiaries, bringing the number up to 30. The dwellings were generously appointed relative to comparable accommodation elsewhere, with living rooms of 13ft by 11ft (4m by 3.4m) and kitchens of 12ft by 11ft (3.7m by 3.4m); other rooms seem to have varied in size. The architects took the decision to turn the principal frontage towards the busier of the two thoroughfares, which links Faversham with its satellite of Ospringe (now effectively absorbed into the town) on the Roman Watling Street. The ground slopes across the site and extensive groundworks, carried out by a local contractor, were needed to provide a level terrace before Chinnock’s of Southampton could move in to begin construction. The foundation stone was laid on 8th August 1862 and the first houses were ready for occupation by June the following year, but work on the chapel seems to have dragged, since it not dedicated until September 1866.

With such a long frontage composed of repeated identical units, there was a real danger of monotony, and indeed the fenestration follows a set pattern. But thereafter Hooker and Wheeler deployed every weapon in their arsenal against it. How is this done? Firstly, the elevation is articulated into a series of advancing and receding planes. At first floor level, alternative pairs of front bedrooms break forward over the covered walkway, united above by a shared gable. Yet the intermediate pairs also break forward slightly (and on both floors), each one independently, its presence emphasised with a hipped roof. The openings of the covered walkway aligned with the entrances to the dwellings are paired, like the doorways behind them. The openings in front of the sitting room windows are, naturally enough, wider and also higher, breaking through the eaves line of the walkway into dormers in order to admit extra light. In between the bays that break forward at first floor level, the covered walkway is supported by elegantly slender columns, their shafts made of cast iron, set on tall bases of complex form and capped with typically High Victorian overscaled foliate capitals, all of which makes of each of them a complex, highly sculptural form. The arcade has a monumentality that belies its almost toy-like proportions, which only become evident on close inspection.

Where the arches have to be load bearing, naturally enough they are bulkier and the articulation into pillar and arch is dispensed with. Thus an ABBC rhythm is established – or would be, were it not for the fact that the arches of the endmost bays of the walkway (i.e. those that adjoin the chapel or the cross wings) are trefoiled and rise up into crocketed gables. The same units are cut and reshuffled for the lateral fronts of the crosswings, where the openings of the covered walkway follow an AABBABBAA pattern. The end elevations of the cross wings have handsome polygonal gables at first floor level growing out of a buttress at ground-floor level. In the inner angles of the returns are towers with tall, hipped pyramidal roofs. These originally housed water tanks, fed by wells on the premises, though the system proved so unreliable that by 1864 negotiations were in hand to connect the complex to the municipal supply. Red brick with Bath stone dressings and banding was chosen for the facing material, as it was thought to be warmer than the Kentish rag popular at the time for Gothic buildings. White bricks are used in places to achieve sparing but effective polychromatic patterning for some of the arch heads and relieving arches, and also for the splendid bases of the chimney stacks, which sport set-offs that are both striped and tumbled.

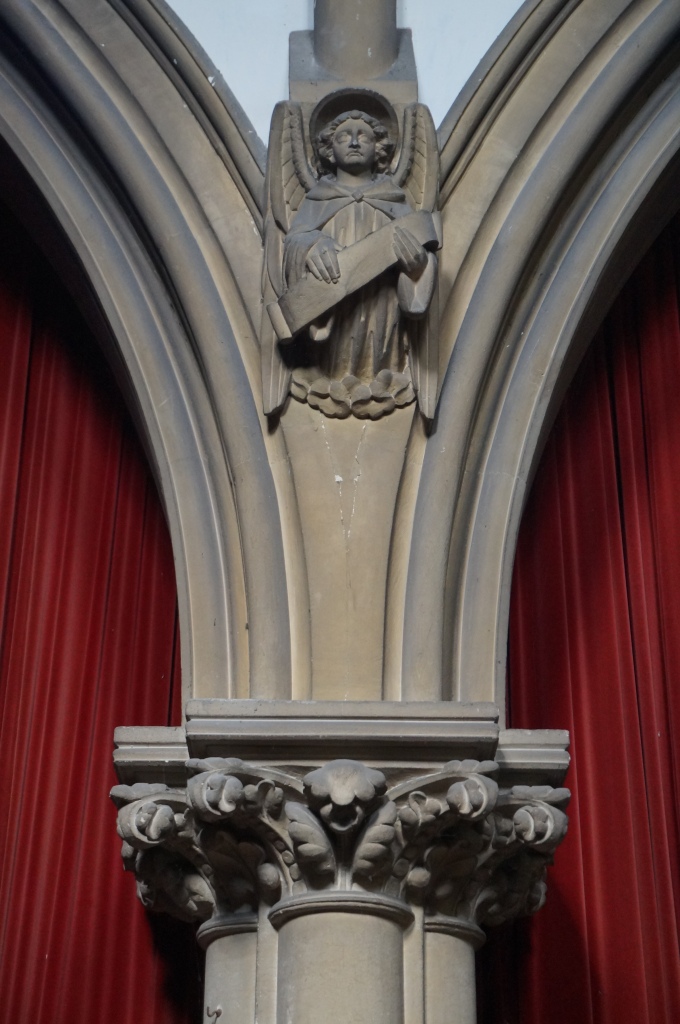

Ashlar Bath stone facing was used for the chapel to set it off against the surrounding expanses of red brick, but in any case it could hardly fail to stand out. A substantial building, it was intended to seat a total of 220 people, considerably in excess of the 60 sittings to be provided for the residents. The tall, narrow proportions, the polygonal apse and the Geometrical Decorated tracery allude to the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, a popular model at the time for institutional places of worship. But instead of a tall flèche astride the roof ridge, two octagonal turrets rise from the lobbies either side where the covered walkway meets it. The internal proportions are imposing. Tall shafts supporting the roof trusses mark off each bay and the slightly overscaled ornament beloved of High Victorian Goths abounds. The chapel departs from its model in having short lean-to aisles of two bays and large areas of blank walling in the nave – inevitable, given that it is abutted here by the residential wings. The interior was initially to have been faced with ashlar, but when the tenders were opened they were in excess of the £11,000 budgeted for construction and Hooker and Wheeler, in cooperation with Ferrey, devised a number of cost-cutting measures of which one was substitution of the ashlar facing for a plastered surface. Initially the glazing was entirely plain and all the colour was concentrated in the gorgeous Minton tilework of the sanctuary, with encaustic tiling used not only for the floor, but also for the wall panelling where it forms a setting for carved roundels. No stained glass appeared until 1895, when scenes from the Life of Christ by Lavers and Westlake were introduced in the apse windows. In 1911, the former east window from the parish church of St Mary of Charity – a major work of 1844 by Thomas Willement (1786-1871), who had resided at nearby Davington Priory – was installed here in the large traceried window at the west end.

The almshouses have survived well and remain in use for the purpose for which they were built. The chapel spires were taken down in 1964 because of concerns over their safety, but reinstated in 1991, albeit slightly smaller than before. The external ironwork, which must have fallen prey to the scrap drives of World War II, was reinstated around the same time. In 1982, an extensive refurbishment was carried out, which included the subdivision of the west end of the chapel to create a community space for residents. In 1989, new accommodation blocks were added, tactfully positioned and scaled to keep them visually subservient to the main building. By the time the original construction campaign had finished, Wheeler and Hooker were no longer working together, their partnership apparently having been dissolved in c. 1863. Hooker apparently remained in architectural practice until c. 1889, despite having been declared bankrupt in 1886, following which he moved to Philadelphia where his son was already living. What he designed and where remains to be discovered.

What Wheeler did next: the churches

Wheeler remained active until at least the mid-1880s (when he may have added the bell tower to the church of St Paul in the Margate suburb of Cliftonville, which would make it his last known commission), practising first from Brenchley, then from Tunbridge Wells and finally from London, although he retained the appellation ‘Wheeler of Tunbridge Wells’. He was active chiefly in Kent and seems to have developed a line in ecclesiastical work. None of the restorations identified so far (St Nicholas, Otham in 1864-1865 and the tower of St George in Wrotham in 1876) is of especial interest, but some of the new churches are rather characterful. For the most part, these are relatively modest buildings. In 1863, Wheeler produced a design for the chapel of what was originally established in 1836 as Tonbridge Workhouse (subsequently Pembury Hospital). Though the site was cleared for wholesale reconstruction in 2011, the chapel survives. It is a robust piece of a design in a High Victorian idiom already more strident and vigorous than the Faversham Almshouses. Very compactly massed, the chancel (flanked by separate entrances for male and female paupers) projects only a short distance out of the main volume and the aisles are gathered in under catslide roofs. All external mouldings – dripstones, string courses, corbels and sills – are dispensed with, underscoring the effect of an indivisible mass. The east window reads as a series of foiled openings punched through the wall surface, not articulated into a unified composition by jambs, mullions and an arch – a favourite device of roguish architects of the 1860s. Internally, the nave and aisles are separated by arcades of three wide bays, the arches vividly striped and supported on stout columns of polished red granite with spreading foliate capitals, making this an unusually elaborate example of a building type whose architecture was usually every bit as austere as the ethos of the institutions they served.

Much of this manner is also in evidence at All Saints in Horsmonden, built in 1869-1870 as a chapel-of-ease to the village church of St Margaret, which is situated a good two miles to the south of the titular population centre. Located on Maidstone Road, it served outlying hamlets and farmsteads in the northern half of the parish. It is a compactly composed mass of stock brick with red brick dressings, here with an apsidal sanctuary. The nave is slightly wider than the chancel, but essentially the building consists of a single volume. There was originally a steeply gabled bellcote over the junction of the nave and chancel, but this was blown down during the Great Hurricane of 1987 and not replaced. Made redundant as an Anglican place of worship in 1970, All Saints then served as a Catholic church until in time becoming surplus to requirements for this purpose too, following which it was converted to a house in 2020. The interior was a satisfying period piece, which demonstrated the cave-like effect beloved of High Victorian architects (often described as ‘speluncar’ in contemporary literature), achieved by fenestrating the building entirely with narrow lancets with deep reveals, those in the apse fitted with richly coloured stained glass by O’Connor and Sons installed shortly after completion. The wall surfaces of red brick with black banding set this off effectively, as they did also the marble colonettes on angel corbels supporting the chancel arch and marble-fronted pulpit, all of which were adorned by the vigorous stiff-leaf carvings typical of the style. The timber fittings were removed for the conversion, but the east end of the nave and the chancel have fortunately been left unsubdivided, allowing the patterned ceiling of the latter to be appreciated.

St Clement’s in Leysdown on the eastern tip of the Isle of Sheppey of 1874 was a typical mid-Victorian smaller rural church, which replaced an even more modest predecessor of 1753. Externally it seems to have been faced in flint or rubble-coursed Kentish rag (archive photographs are a little difficult to interpret) with brick and stone dressings. There was plate tracery to the nave windows and colonettes supported the three belfry openings. Constructed without adequate foundations, it suffered from structural problems and was eventually demolished in 1980. No images of the interior have yet come to light. St John’s in Swalecliffe of 1875 has a number of points of similarity with St Clement’s, not least a windswept, shoreside location on the outer reaches of the Thames Estuary in what was, until post-war expansion, a lonely and sparsely populated spot. It also stood on the site of an older predecessor. The most effective design feature of the exterior is the rectangular bellcote mounted on a truncated pyramid straddling the west end of the nave. Though it is a modest and simple building, there is a good deal of enjoyment to be had from the varied palette of materials and detailing, much of it quite literally the stock-in-trade of a mid-Victorian contractor, such as the varied shapes and colours of the tiles and slates. Happily, this was little eroded in the 20th century.

As at Horsmonden, the interior is faced in red brick with black banding and, again as with that church, embellishment is reserved for the marble-faced pulpit and attached columns borne on corbels (here geometrical rather than figurative) supporting the chancel arch. The chancel roof is ceiled with panelling that has been stencilled with a repeated designs on a coloured ground. This exhausts the original decorative scheme and later enrichment has gone little beyond it. St Lawrence’s in the tiny village of the same name on the Dengie Peninsula in Essex, built in 1878, is another towerless, two-cell church. Externally, there are greater pretensions to grandeur in the use of Perpendicular Gothic tracery and dressed ragstone for the facing, while the fine octagonal bell turret is a good landmark in this flat, open country. The interior is decent and carefully detailed but plain, the only noteworthy feature being the panelling in the sanctuary incorporating Decalogue boards, an old-fashioned feature for the date.

Only one urban church by Wheeler has so far been identified and that was St Paul’s in Ramsgate. It was established by curates from St George’s, the grand parish church built in the 1820s to serve the resort town that began to grow up by the harbour in the late 18th century. More churches appeared in the town during the course of the following decades, but religious life at places of worship that saw themselves as ministering to a smart watering place alienated the impoverished locale of King Street, which stayed away. A mission church was established and a site acquired in early 1873. The foundation stone was laid in November of that year and the building opened for worship the following May. Wheeler provided a modest building, 69ft (21m) in length and 30ft (9.1m) in width, faced in red brick with black banding internally and white brick with stone dressings externally. It had a south aisle, but there can have been little opportunity for architectural expression since the site was hemmed in on two sides by existing properties and only the east wall was fully exposed to view. An archive photograph suggests that this had twin two-light windows of plate tracery.

The population of the neighbourhood grew and, with it, the congregation, making it necessary to enlarge the building. The existing nave would be retained and incorporated into a new structure, of which it would form the north aisle. Work began in July 1886 and the remodelled church was consecrated in January the following year, three months before St Paul’s became a parish in its own right. More research is needed to establish the authorship of the second phase: the ground plan in the collection of the Incorporated Church Building Society is signed by Henry Hinds (1834-1924), a local surveyor, but this may not be conclusive proof. Much of the design of the new nave and chancel had affinities with Wheeler’s work elsewhere. Then again, by the mid-1880s many of these devices were well established in the architectural vocabulary of the period and producing a passable imitation of the manner would have required no special skill. Two of the red granite columns from the old south arcade were saved and incorporated into the new baptistry. Conceivably other features, such as the south aisle windows (there were two tiers of fenestration in the south wall of the enlarged church), were salvaged and reset in order to cut costs.

The most distinctive features of the remodelled St Paul’s were the porch tower, squeezed in between two adjacent properties on Sussex Street and linked to the north aisle by a vestibule, and the apse. The latter was a curious design, following the segment of a curve rather than a full semi-circle like a bow window, perhaps a contingency forced on the architect by the limited space available on this constricted urban site. Following the Dunkirk Evacuation in 1940, St Paul’s was closed amid fears of an imminent German invasion. Bombing raids later that same year destroyed numerous houses in the parish, including several in close proximity. The church itself was largely undamaged, however, and it was hoped that it would be able to reopen after the cessation of hostilities. But much of the congregation had now been scattered and reputedly the measure was strongly resisted by the then-rector of Holy Trinity (located a short distance away and also very Anglo-Catholic in its churchmanship), who feared that St Paul’s would lure away his own congregation. The building remained shut and eventually in 1958 the parish was subsumed back into St George’s. St Paul’s was demolished the following year.

What Wheeler did next: Harvey Grammar School

Intermittently engaging though all these churches can be, it is difficult to recognise in them – insofar as any meaningful and objective comparison is possible – an architect operating at the same level of inspiration as the Wheeler who had collaborated with Hooker on the Faversham Almshouses. Was the panache of that design entirely the contribution of his former partner? Another work of the 1880s suggests that it may not have been. Dr William Harvey (1578-1657), discoverer of the circulation of blood, bequeathed £200 to his native Folkestone ‘to be bestowed by the advice of the Mayor thereof and my Executor for the best use of the poore’. It seems that his younger brother, Eliab Harvey the Elder (1590-1661), who acted as executor, interpreted the establishment of a grammar school as a worthy use for the bequest. But nothing was done until 1671, when a site was purchased on Rendezvous Street, by which time Eliab Harvey the Younger (1635-1699) had taken charge of affairs. The foundation deed is dated March 1674. For this and all the information that follows, I am indebted to A History of the Harvey Grammar School by the Rev’d J. Howard Brown (1962).

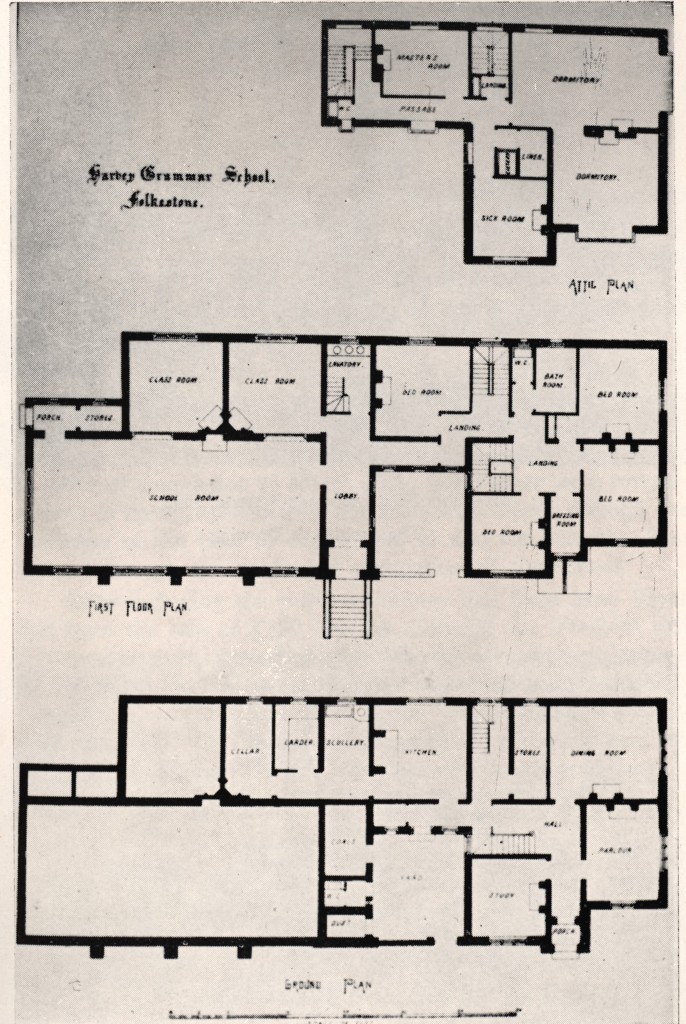

By the middle of the 19th century, the original building was in a poor state of repair and in 1845-1846 it was taken down and replaced by new premises on the same site. These were jerry-built and, in any case, quickly turned out to be inadequate in capacity for a town whose population was growing rapidly during a period when it had gained a rail connection and was fast developing as a bathing resort. In late 1877, the school’s trustees resolved to approach the agent of Lord Radnor, the principal local landowner, for a new site. They managed to secure one on Foord Road, a little to the north of the medieval centre of the town, on land which at that point was occupied by nursery gardens. Initially they intended to commission the design from one William King of Ashford, but in late 1880 changed their minds and instead approached Wheeler. Construction began in mid-1881 and the school opened on 31st July the following year. The plan followed the usual configuration in having teaching and residential accommodation under one roof. There was a large principal schoolroom, 50ft by 25ft (15.2m x 7.6m) in size and intended to accommodate 150 boys, with two smaller ones opening off it to the side. At the east end this was adjoined by residential accommodation for the Master and Assistant Master, although with a sick bay and dormitories for the boys in the attic.

The site was a difficult one, sloping steeply from west to east (which perhaps explains why the Earl of Radnor’s agent had been willing to make it available at well below market price), but Wheeler turned this to good effect with his deft planning and massing. The residential portion was positioned at the lower end of the site with the schoolroom behind, raised up on a basement and communicating with it at first-floor level. The building was asymmetrically composed to dramatic and picturesque effect, and over the porch to the schoolroom rose a tower with a tall hipped roof – far larger than it realistically needed to be for the single bell used to summon the boys to lessons, but an effective vertical accent that gave the school presence in the townscape. Aspects of the design of the residential portion, such as the tile-hung upper storeys and dummy half-timbering, show that Wheeler had absorbed the influence of the vernacular revival initiated by Shaw and Nesfield. But the manner of the bell tower was still patently High Victorian and the busily variegated colours and textures of the wall and roof surfaces reflected preoccupations of two decades earlier.

The site proved to be not just inconvenient, but ultimately the building’s undoing. The town’s population continued to expand and, once again, the institution began to outgrow its premises. By the end of the 19th century, all the surrounding nursery gardens had disappeared under residential streets of semi-detached villas and the school was hemmed in on all sides with no room to expand. In 1913 it moved out to a new campus near Folkestone West station and Wheeler’s building became a clinic, remaining in medical use until it was sold for residential conversion. Despite having spent most of its life serving functions other than those for which it was designed, the fabric survives well, with little erosion of the detailing.

Conclusion

The aim of this blog is to retrieve from obscurity Victorian architecture which has been overlooked or forgotten. Most of what Wheeler and Hooker designed might justifiably be placed in this category. But any claims of unjust neglect need to be interrogated. Why should certain architects have such little name recognition? Why should a whole life’s work be known only to a handful of cognoscenti? In the case of practitioners such as R.J. Withers, the answer lies in the geographical distribution of their output. They built mainly in scattered or little frequented locations and it takes time, effort and mileage to build up a sufficiently full picture of their work for one to begin to draw conclusions about its quality and significance. With others, such as T.E. Knightley, ill fortune is to blame. They have been cheated of the recognition by accident, war and wanton destruction, which have robbed us of works that ought firmly to have established their reputation. But in the case of Wheeler and Hooker, we are dealing with architects who fall into a very different category. What by any standards is a notable and indeed very visible work survives to testify to real talent and ability. But that forces one to ask whether the remainder of their output equals or falls short of it in architectural quality.

The buildings presented here can hardly represent an exhaustive survey of the either man’s life and work and thus this post raises numerous questions. What else did Hooker and Wheeler design while they were still in partnership? Which of the two was the chief source of inspiration for the design of the Faversham Almshouses? Why was the partnership so short-lived? What did Hooker go on to build after the dissolution of the partnership and was it very different? Did Wheeler design anything other than churches and schools? Are the surviving works wholly characteristic of his style, or are there buildings waiting to be discovered – including lost major works – that might change our perspective on him? Certainly the two architects deserve a comprehensive study, but I cannot help wondering how fruitful pursuing any of these lines of inquiry might be in advancing our understanding of them. Many of the buildings that we have seen are best understood as good period pieces. They are wholly characteristic of their date and, indeed, wholly characteristic of their designer, but significant in a local rather than a national context.

None of this should be interpreted as a slight. The further in time we regress from our own period, sometimes the less exacting the critical standards we apply to architecture, whereas in the case of something as arresting as the Faversham Almshouses – the product of an age that is well documented and where the architectural historian is less often thrown back on conjecture and speculation – we feel entitled to judge it by more exacting standards. Yet not every Victorian building is the work of a William Burges or a Norman Shaw, just as not every Stuart building is the work of a Christopher Wren, or every Georgian building that of a Robert Adam. The histories presented in this blog are as much histories of place, personalities and circumstance as they are of construction and design. The trustees of Wreight’s legacy could have selected as winner any one of a number of entrants to the competition for the new almshouses, but they chose Hooker and Wheeler. Faversham is fortunate to be able to boast such a magnificent statement of High Victorianism, but Hooker and Wheeler were equally fortunate that an opportunity presented itself that played to their strengths and gave them a chance to show their mettle. They were the right men for the right job at the right time, and perhaps it is that, rather than any attempt to account for unrecognised genius, that ultimately is the key to understanding their legacy.

Really enjoyed your piece.

All my children went to nursery in Hooker’s school in Hertford, still sitting comfortably in the town.

LikeLike

I live in Swalecliffe, and walk and cycle past the little church all the time, and have always been curious about the architect. It is delightful to find that Wheeler (in partnership) was also involved in designing the brilliant Faversham Almshouses. And it does lead one to wonder how the credit should be divided for that imposing, confident group of buildings.

Thank you for a fine article.

LikeLike

Thanks for you kind comments and I’m glad you enjoyed it! Knowing what to attribute to whom is always difficult in the case of work by a partnership, but there is a certain pizzazz about the almshouses that disappears from Wheeler’s work after he goes solo.

LikeLike

Thank you firstly for the excellent photos and also for this presentation of whom is now one of my favourite architects. Such fine proportion and originality .

LikeLike