One is the former London office of a firm that produced vinegar and fortified wines. The other is a speculative development of townhouses aimed at the affluent middle classes. Fairly mundane projects typical of the 19th century, one might think; typical, indeed, of hundreds such up and down the country, brought into being by the commercial and demographic expansion of the period. Yet little Victorian architecture elicits such strong reactions or has prompted quite so much speculation about the intentions and moral qualities of the designer as Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap in the City of London and Milner Square in Islington. It would, I think, be fair to say that the reputation of both works precedes that of their creators. Indeed, judgements pronounced on both works by 20th century commentators stick in the mind more firmly than the names of the architects. For Ian Nairn, the former was ‘truly demoniac, an Edgar Allan Poe of a building’, and ‘the scream you wake on at the end of a nightmare’. For John Summerson writing in Georgian London, the latter invited similar metaphors. The architecture had ‘an unreal and tortured quality’, and ‘It is possible to visit Milner Square many times and still not be absolutely certain that you have seen it anywhere but in an unhappy dream’.

It should come as no surprise that the architect of both buildings, Robert Lewis Roumieu (1814-1877), was included by H.S. Goodhart-Rendel in his lecture of 1949, Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era. Yet in contrast to the astonishment and admiration expressed towards other architects whose work he surveyed in it, he viewed Roumieu and his sometime collaborator Gough with sniffy disdain. ‘In any serious history of English architecture Roumieu would be a negligible figure… his aesthetic rakishness for all its violence is eventually dull’. For him, both men’s work was less the stuff of nightmares than puerile attention-seeking: ‘in general either singly or together, they seldom fail to be vulgar without being either funny or interesting’. In my post on the buildings of the Foxwarren Estate, I pondered the motives imputed to certain Victorian architects and cautioned on the need when assessing their work to withhold reactions conditioned by extra-architectural associations, which sometimes arise from 20th century popular culture.

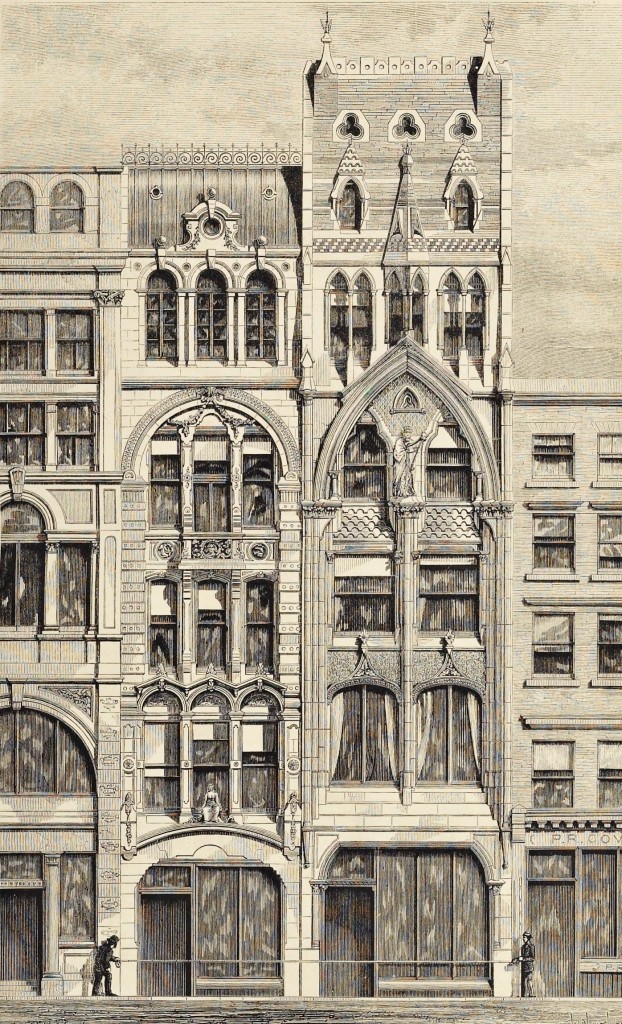

Contemporary accounts are often far more revealing, and so it is in the case of Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap. The Building News of 25th September 1868 praised the building as an authentic expression of its time. It was ‘English Gothic of the middle of the nineteenth century, and not bad Gothic at that. […] We are far from saying it is perfect, or, indeed, any great way on the road to perfection, but it is an honest and earnest effort’. While the anonymous commentator felt that the architect was guilty of indulging his client’s extravagance, criticism was aimed more at the indiscriminate juxtaposition of devices that he ought to have recognised belonged exclusively to the domain either of timber-framed or masonry architecture of the Middle Ages. But though ‘[we] do not care to see the principles mixed’, the author conceded that ‘we should be glad to see three or four dozen buildings designed with as much care and carried out with as much skill’. The construction was praised as ‘scientific’ and the hand crane with an extendable jib for lowering casks into the basement storeroom was viewed with as much admiration as any architectural feature.

Rhetoric and conjecture can sometimes lead the architectural historian astray. So too can assessing a building in isolation from its architect’s career. For all the ink spilt about Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap and Milner Square, comparatively little attention has been paid to the remainder of Roumieu and Gough’s output. Whatever the inferences made about their creators’ underlying temperament, these two works are sufficiently different stylistically to suggest considerable variety in expression, and they make one curious about their context. Where did such alarmingly original architecture spring from? What else did Roumieu and Gough design? Were they Goths, Classicists, or both? And do Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap and Milner Square – or did they ever – have counterparts elsewhere? The aim of this post is to provide answers to some of these questions.

Background and training

Roumieu was born into a family of Huguenot extraction, which reputedly originated from Languedoc and had settled in Britain as part of the first wave of Protestant emigration following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV. His grandfather Abraham Roumieu (1734-1780) was an architect, who in 1748 served part of his apprenticeship with Isaac Ware (1704-1766). In 1766-1767 Abraham Roumieu produced a scheme jointly with John Adam (1721-1792), commissioned by the 4th Duke of Gordon, for remodelling the medieval Gordon Castle in Morayshire, Scotland. This survives in the National Archives of Scotland, but was never carried out and indeed no executed works by Abraham Roumieu have so far been identified. Robert Roumieu’s architectural training seems to have begun in 1831, when he was articled to the eldest son of James Wyatt, Benjamin Dean Wyatt (1755-1855), who in the 1810s-1820s had a flourishing practice in London. This had begun with the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane: a competition was held in 1811 to find a design for a rebuilding following the destruction of the previous theatre by fire in 1809, and Wyatt emerged victorious. Two years later, he succeeded his father as surveyor to the fabric of Westminster Abbey, a post which he held until 1827, but, with this exception, he did not involve himself in ecclesiastical architecture, specialising mainly in country house work. In London, he handled a number of commissions for townhouses and club buildings. He produced an unexecuted design for a palace for the Duke of Wellington and, jointly with his younger brother Philip, in 1828-1829 remodelled Apsley House on Piccadilly, the Duke’s London home. When Roumieu was serving his articles, Wyatt was working on the Duke of York’s column in Carlton Gardens.

In 1836, Roumieu set up a partnership with Alexander Dick Gough (1804-1871), who had also been a pupil of Wyatt, rising to sufficient prominence in the office to be entrusted with superintending several of the practice’s more important works, including Apsley House and the Duke of York’s column. The new firm was based on Regent Square in St Pancras and most of its commissions were for sites within a fairly narrow radius of this address. Wyatt was a practitioner of a grand but not especially adventurous brand of neo-classicism. By contrast, his former pupils quickly revealed themselves to have idiosyncratic and strongly individual architectural personalities.

Roumieu and Gough the classicists

The earliest building to be executed by the partnership was built in c. 1837 on a site just off Upper Street in the centre of what at that date was in the process of rapid transformation from a village to an inner suburb of London. It was the premises of the Islington Literary and Scientific Society, which had been established four years previously to spread knowledge through lectures, discussions, and experiments. The project was the first major commission of William Spencer Dove (1793-1869), an Islington builder whose sons in 1852 formed the Dove Brothers partnership, a prolific contractor which worked with numerous prominent 19th century architects, including, as we have seen, Bassett Keeling. The Institute’s facilities comprised an extensive library, a reading room, a museum, a laboratory and a lecture theatre. The street front was symmetrical and handled in a stripped classical manner. To modern eyes, this prefigures much official architecture of the 1930-1950s, but it had been born out of the Greek Revival and prototypes such as the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllus, which had been illustrated in Nicholas Stuart and James Revett’s The Antiquities of Athens.

The street front is a nervous and restless composition, which packs a great deal into a small amount of space. The openings – doors, windows, even blind openings – all of them trabeated, are deeply recessed and unusually narrow in relation to their height, often being only slightly greater in width than the pilaster strips that divide them. It seems that this architectural language was continued into the auditorium, which seated 500. The walls were blind and the space was lit directly only by an elegant oval roof lantern very much in the manner of Soane, although borrowed light also reached it from the first-floor library, which communicated with the auditorium through a double screen. This incorporated a pair of Ionic columns on the inward-facing side, the visual impact of their sculptural forms much amplified by the severely rectilinear modelling of the wall surfaces and ceiling. Now listed at Grade II, the building survives and since the early 1980s has been home to the Almeida Theatre, but it has been considerably altered internally. It ceased to be used for its original purpose in 1874 and subsequently went through a variety of uses, including a spell lasting from 1890 until 1955 when it was a citadel of the Salvation Army, which turned around the auditorium by 180 degrees so that the seating was focused on the end of the building furthest from the street.

The active development of the rural northern fringes of London with new suburbs of housing aimed at middle-class buyers provided extensive opportunities for architects, which Roumieu and Gough were evidently quick to exploit. In c. 1839, work began on a development at Nos. 96-108 Tollington Park in Holloway. Going by what can be deduced from map evidence and what survives on the ground, it seems that the concept was based on a symmetrical plan with a central detached villa flanked by two pairs of semi-detached villas. Although they appear at first glance to constitute a group of discrete masses, the villas in fact form a continuous range, being joined to each other by lower service wings on semi-basements. None is listed and they have been subjected over the years to numerous unsympathetic alterations, which have eroded much of the original detail, while the northernmost pair has been completely lost. But the architectural language, based on breaking up the façade into narrow subdivisions through the liberal use of pilaster strips to form a pattern of deep blind and glazed recesses (the effect is underscored by the use in the latter of sashes with margin lights) can be appreciated at No. 104, the centrepiece of the composition, which appears still to reflect well the architects’ intentions. Here, the triplets of arched windows that are one of the signature traits of Victorian Italianate put in an appearance at first-floor level.

The already idiosyncratic architectural language in evidence in these two commissions was taken to an extreme when Roumieu and Gough embarked on Milner Square in Islington. This was the final stage in the development of an estate on the west side of Upper Street belonging to Thomas Milner Gibson, which occupied an area enclosed by Theberton Street to the south, Barnsbury Street to the north and Liverpool Road to the west. Development began in the 1820s, but proceeded slowly. Milner Square seems to have been laid out in c. 1827, but the sites on the east side were not leased to builders for development until the 1840s and the ensemble was only completed in the 1850s. The holdings of the lessees were scattered and development correspondingly piecemeal and uncoordinated, with the exception of William Spencer Dove, who had 44 houses – the only unbroken run anywhere on the estate – some workshops and building land on Milner Square. The square is positioned on a north-south axis and elongated in plan, its length being roughly twice that of its width. There is access from Barnsbury Street to the north and Gibson Square to the south.

Whatever emotional reactions Milner Square provokes, it unquestionably marks a very radical departure from the architectural treatment of terraced townhouses that had prevailed in London for most of the long 18th century. The most striking feature is the way in which individual dwellings are subsumed into the whole. Whereas designers of a previous generation might have adopted such a tactic for the sake of a grand overall controlling composition – say, a portico embracing the properties at the centre of a long symmetrical façade – here the treatment of the elevations is based on repeated units and indeed, above ground-floor level the bays are all identical. The architectural language is familiar from the former Literary and Scientific Institute (located only a stone’s throw to the west) and again has a strongly vertical emphasis, with the elevations at first-floor and second-floor level divided up into strips that are dizzyingly tall in relation to their width. All the openings are trabeated, with the exception of the attic windows, which are arched, but these are so narrow and the curves of the arches so subsidiary to the effect as a whole that they provide little relief. With the exception of the continuous frieze and cornice marking off the attic storey and blocking course above, every part of the elevation is in continual restless movement as an endless series of advancing and receding planes. Though one might opt for the term ‘neo-classical’ if pushed to affix a stylistic tag, conventional terminology for parsing such designs is of little help in rationally analysing the visual impact. It is perhaps this, together with the sense that it is all too easy to imagine how the vertical units might appear if repeated ad infinitum, which explains why Milner Square has provoked such extreme reactions. ‘It is as near to expressing evil as a design can be’, wrote Ian Nairn.

Yet conceivably, this is to some extent the result of accident as much as design. It was common at the period for major new residential developments to have their own place of worship and the Gibson Estate was no exception, with a proprietary chapel and a school built in c. 1830 flanking the entrance to Milner Square from Barnsbury Street to the west and east respectively. Aerial photographs show that the chapel was an unassuming, box-like structure that did not rise above the parapet of the adjacent houses. The school, which was designed by John Newman (1786-1859), was a plain classical design with Georgian Gothick fenestration that was subsequently much enlarged. Neither was a major architectural statement and both have been demolished. It seems that when the western side of Milner Square was at the planning stage, a new church was mooted to supersede the existing proprietary chapel. A perspective drawing of the street front in the collection of the RIBA depicts a florid Greek Revival design, which would have given the square an imposing focus and challenged the monotony of the elevations. An inscription on the drawing records that it was intended to be built in the middle of the west side, to occupy a site 60 ft (18.3m) in breadth and 90ft (27.4m) in depth, and to provide seating for 1,000 worshippers. The design is undated, but Roumieu gives his address as Lancaster Place, which means that it cannot be earlier than 1845 when the practice moved there from Regent Square. This was, coincidentally, the same year that he became a fellow of the RIBA.

The street front seems to have been influenced by that of St Mark’s, North Audley Street in Mayfair, built in 1825-1828 to the design of J.P. Gandy (1787-1850), although the model is much elaborated. The whole portico in antis is brought forward, the columns are Composite rather than Ionic, and above there is a small pediment with antefixae, while the debt of the bell turret to the Tower of the Winds is more pronounced. Again, there is a patent mania for breaking up every part of the elevation into tall and narrow subdivisions and a fascination with layered surfaces and spaces. This same fascination is in evidence in the view of the interior, also held in the RIBA collection, where similar devices are used to create a mysterious, somewhat indeterminate space behind the pulpit, which forms the visual focus of an otherwise austerely rational and severely rectilinear design. Why the Milner Square church was never executed is currently unknown, but several elements of the street front were recycled in an even more florid design forming part of an apparently unexecuted scheme for a Protestant church in Versailles. This was perhaps the Anglican church on rue Hoche, established in 1821 in a chapel originally built for Catholic worship, and shared from 1828 onwards with French Protestants. The design of the neighbouring buildings, which (assuming this is the same site) are entirely the result of artistic licence. suggests a date a good 10-20 years after the Milner Square scheme, but nothing of the circumstances of this commission is currently known.

The rapid development of the northern fringes of London at the time when the Roumieu and Gough practice was active in the area makes it at plausible that there is more residential work by them awaiting discovery, attribution and study. The National Heritage List for England ascribes to Roumieu Nos. 13-19 Craven Road and Nos 1-18 Spring Street in the vicinity of Paddington Station – conjecturally and on the basis of the treatment of the elevations, which have slight affinities with Milner Square. The dating is uncertain, which leaves open the question of whether (assuming the attribution is accurate) the design was the work of the partnership or Roumieu on his own. We are on firmer ground with the alterations carried out in 1840-1841 to The Priory in Roehampton, the Georgian Gothick mansion which at that date was the residence of the barrister, judge and MP Sir James Lewis Knight-Bruce (1791-1866), now better known as a private hospital treating mental illness and substance abuse. The partnership carried out extensions to the existing building and a design for a fireplace combined with bookcases is held in the RIBA collection.

Roumieu and Gough do Norman, Gothic and Tudor

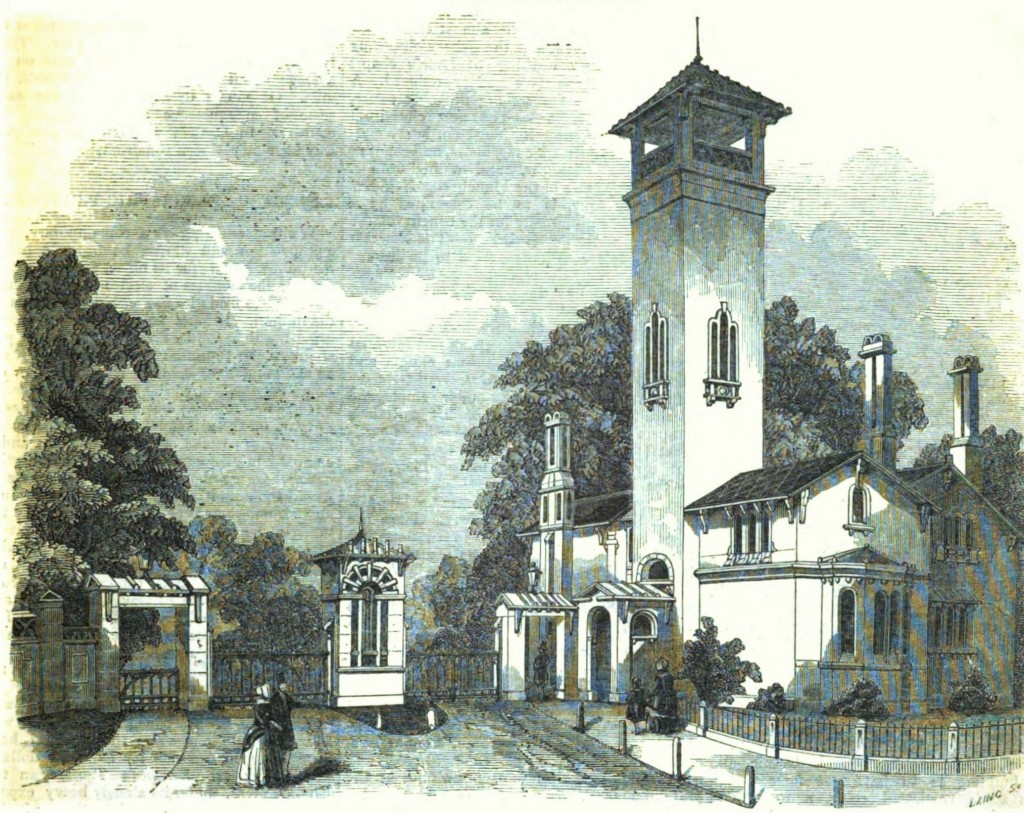

The choice of Gothic for the additions to The Priory was presumably conditioned by the style of the existing fabric. But it was in any case rare in the 1830s-1840s for any practitioner to be exclusively a classicist, and Roumieu and Gough designed in the wide range of styles of which architects at the time were expected to have a command. They showed themselves to be every bit as outlandish in their interpretation of the architectural language of the Middle Ages as they were with that of Classical Antiquity. In 1842, they were engaged to carry out alterations to St Peter’s Church in Islington, built in 1834-1835 on a site about half way between Islington Green and the Regent’s Canal as a chapel-of-ease to the old parish church of St Mary. It was the work of Sir Charles Barry (1795-1860) and evidently built on a rock-bottom budget, for even by the standards of the time it was starkly plain – a stock-brick preaching box in a lancet style with minimal gothic detailing. Roumieu and Gough added a new entrance front to Devonia Road with a bell tower, transepts and a short chancel, perhaps aimed at giving greater dignity to what in 1839 had become a parish church in its own right.

The additions to the main body of the building were similar to Barry’s original fabric and barely any more elaborate, although the triple lancets in the east wall were handsomely shafted internally, along with the chancel arch, and the chancel ceiling was vaulted in plaster. But the additions to the west end were downright startling. The entrance front of Barry’s chapel had had a tall, cavernous arch. Perhaps it was this that suggested the addition of an outer screen wall to give the triple lancets (which were not present in the original design) exaggerated depth. Then again, this may equally well have been a product of the fascination with layered space and openings that we have already seen in the scheme for the Milner Square church. What looks at first sight like a porch is in fact yet another screen wall, with cusped details and shafting to the main portal and triple openings either side to create a visual focus. The central arch is filled with what must be cast iron tracery, which descends to a hanging pendant. This is still Georgian Gothick in spirit, and, as such, not wholly unexpected for the date. But the extraordinary steeple shows free invention taken to an alarming extreme. A tall, thin narrow core rises to a spire in the form of an obelisk with chamfered corners, the upward flow unchecked by any cornices or string courses. Enormous cruciform buttresses extend from each corner, rising in the upper stages to turrets, from which flying buttresses spring inwards as if to stop the crazily attenuated belfry and spire from tottering over. On Grantbridge Street at the rear of the site, Roumieu and Gough added a school building. What survives today is plain, stylistically rather nondescript and appears to have been much altered (the church was declared redundant in 1982 and the complex turned over to other uses). But a drawing in the RIBA collection depicts an imposing essay in neo-Elizabethan, delivered with enough concern for archaeological accuracy to give it a conviction rare for the date and manner. The view also shows the chancel as more elaborate than what was eventually built, with pretty Geometrical Decorated tracery in the east window. This suggests that the design represents an earlier version of the scheme, which had to be simplified in execution, perhaps on grounds of cost, but the precise sequence of events awaits elucidation.

Drawings in the RIBA collection show experiments with neo-Norman that are every bit as outlandish as Roumieu and Gough’s flight of fancy with Early English. One of them is the usual early-Victorian preaching box, but adorned with an attenuated tower and spire to one side of the main front, with a tall, arched central entrance leading into a lofty vestibule, through which an impressive portal can be seen with a wheel window above. The surroundings suggest that the design was envisaged for a rural location. The other is for a larger building in what appears to be a suburban setting. The tower is more substantial and crowned by a cupola instead of a spire, while close inspection of the view suggests that a separate, perhaps apsidal chancel was intended. Again, the entrance takes the form of an tall arched recess in the main front. Individual motifs, such as the portals of several orders, shafted wall arcading with cushion capitals and the corbel tables, have good archaeological precedent, but they are composed with great freedom and applied to forms which at the period were equally likely to be translated into Classical or Gothic. The dates of these designs remain unknown (those suggested in the on-line catalogue entries are clearly spurious) and it is unclear whether they ever got off the drawing board.

But the partnership did get a chance to demonstrate its flair for neo-Norman design when it was called upon to enlarge the old church of St Pancras in 1847-1848. In the 18th century, this was still a village church in a largely rural setting, but the construction of the New Road (subsequently Euston Road) in the mid-1750s dramatically changed that. Over the following decades, central London expanded outwards through Bloomsbury and spilled across it to the north. New squares and streets were laid out and the existing tiny building quickly became inadequate for the much increased population. In 1819-1822 a lavish, grandly-scaled new parish church was built on Euston Square to a Greek Revival design by William Inwood (c. 1771-1843) and his son, Henry William Inwood (1794-1843). The old church was demoted to the status of a chapel, but the population of the neighbourhood continued to expand and the decision was then taken to increase its capacity. In an article published on 21st October 1848, The Illustrated London News reported that, whereas the old building could seat a maximum of 125, following the completion of the remodelling, that figure had been raised to 750. The choice of Roumieu and Gough for the commission is perhaps explained through their engagement by the parish in c. 1846 to erect new national schools on what is now Tankerton Street, a little to the north of Regent Square. A view in the RIBA collection shows an original and effective piece of neo-Tudor design – a considerable advance on the effort in the same manner from four years previously for a combined Free Church and Schools on Paradise Street (now Wicklow Street) a short distance away. The chimney stacks are handled very emphatically, especially the pair that rises from the junction of the main block and the cross wing. The school was short-lived, being demolished in the early 1890s for the construction of a residential complex by the East End Dwellings Company.

The medieval church of St Pancras was a simple, two-cell structure with a stout west tower. This was demolished and the nave extended out over its footprint, the addition clearly distinguished by being narrower than the original nave, while a new tower, which housed a baptistry in its base, was raised on the south side. The work was carried out by W.S. Dove. Some of the detailing, such as the west portal, was surprisingly grand for a such a diminutive building, but this was tempered by the self-consciously picturesque effect of the irregular massing, with the tower set well back and another volume housing the gallery stairs projecting from the south side in front of it. The building was fitted with stained glass by Gibbs & Co. and there was a reredos of blind arcading containing Decalogue Boards against the east wall. Otherwise, the interior did not make quite as proud a show, the result of stringencies imposed by the limited budget (the existing roof structure had to be largely reused, albeit with decorative texts from Scripture applied to the beams) and the nave was dominated by the galleries necessary to provide the extra seating. Roumieu and Gough’s conception is difficult to appreciate today as the church subsequently underwent several major alterations. In 1888 it was refurnished and in 1925 what remained of the galleries was removed, the gallery stairs were partly dismantled and the spire and belfry stage of the tower were replaced by the present half-timbered confection. The east window was partly blocked and all the stained glass by Gibbs has been removed.

Like many architects of the time, Roumieu and Gough were involved in surveying. This could be a lucrative line of business, thanks not only to the rapid development of London and other major cities, but also to the expansion of the railway network. As an engineer, Gough made surveys in 1845, partly on his own account and partly in conjunction with Roumieu, for the Exeter, Dorchester, and Weymouth Junction Coast Railway; for the Direct West-End and Croydon Railway; and for the Dover, Deal, Sandwich, and Ramsgate Direct Coast Railway. Roumieu held a number of surveyorships in his own right, including to the Gas, Light and Coke Company’s Estate at Beckton, where what became one of the biggest gasworks in the world commenced production in 1870. More research is needed to ascertain what these posts entailed, but an insight into this aspect of the partnership’s practice is given by the furnace chimney 140ft (42.7m) high that they designed for Messrs Johnson’s ironworks at Cubitt Town in Millwall, which specialized in converting scrap from naval dockyards into rods and bars.

Roumieu goes solo

The remodelling of Old St Pancras may well have been the last commission to have been executed jointly by the two architects, since the partnership was dissolved in 1848. Gough went on to become a prolific designer of churches, many of them in the suburbs of north London, including St Mark’s in Tollington Park, only a short distance from Nos. 96-108. He also restored a number of ancient ones. Roumieu seems to have cast his net somewhat wider and though ecclesiastical commissions figure in his output, they were clearly not the mainstay of his practice. He remained involved in domestic design but seems to have shifted his focus from residential development to large suburban residences and also took on a limited amount of country house work.

In c. 1865 he added a conservatory to Whitbourne Hall in Worcestershire, the residence of Edward Bickerton Evans (1819-1893). Evans was a proprietor of one of the largest vinegar breweries in the country, located in the centre of Worcester, but he was also an amateur archaeologist who had led an exhibition to Palmyra. It was perhaps this circumstance that dictated the choice of Greek Revival – by that point distinctly outmoded for country houses – when Whitbourne Hall was built in 1860-1862 to the design of local architect Edmund Wallace Elmslie (1818-1889). Why Evans decided to dispense with Elmslie’s services is currently unknown, but Roumieu supplied a design for the conservatory largely sympathetic in character to the existing fabric. He acquitted himself with aplomb in the difficult task of reconciling the massive, trabeated forms of ancient Greek architecture with the skeletal structure required to support the glazing and admit the maximum amount of light. Again, the stripped classical language of the Islington Institute is brought into play, although here the vertical members are whittled away almost to nothing, producing columns that are enormously tall in relation to their slender proportions.

The circumstances of the Whitbourne Hall commission need to be stressed, because as far as it currently known, it represents a stylistic outlier in Roumieu’s work following the dissolution of the partnership with Gough. By the time he set up in practice on his own, he seems to have abandoned Greek Revival architecture and instead was concentrating on cultivating a very personal interpretation of the Italianate style popular at that period. This is evident in one of his first independent works, the lodge to Manor Park in Streatham, completed in 1849. New housing was beginning to encroach on the fringes of this estate occupying the angle formed by the junction of Mitcham Lane and Streatham High Road, and the main house would eventually be demolished for redevelopment in the 1880s. But at this date, the tide of suburbia was not yet in full flood and enough of the parkland was still extant for it to be turned into a public amenity, hence the need for a lodge to house an attendant. It was a substantial dwelling with four bedrooms and two sitting rooms, and it boasted a tower, 70ft (21.3m) in height with a viewing platform at the top, from which, The Builder reported (issue of 7th April 1849), ‘on a clear day Epsom, Harrow-on-the-Hill and Highgate can be seen without the aid of a glass’. Picturesquely composed Italianate villas were common enough in the 1840s and 1850s; what sets this one aside is the almost grotesque attenuation of the tower and peculiar overscaled chimneys, not to mention also the exaggerated blocking to the voussoirs of the arch of the elongated Serliana of the tiny gatehouse in the centre of the roadway. The lodge was located where the main drive leading into the park diverged from Mitcham Lane. It was demolished around 1925 for the construction of the Manor Arms pub, which now occupies the site.

Similar exaggerations and distortions of the language of Victorian Italianate are in evidence in an unexecuted scheme for a bell tower for the church of All Saints, Ennismore Gardens in Knightsbridge (now the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Dormition). This church was built in 1848-1849 to a design in an early Christian manner by Lewis Vulliamy (1791-1871). A sketch in the RIBA collection shows that Vulliamy proposed a tall campanile based closely on Italian models, but funds were in short supply and it fell victim to economies. Roumieu’s flamboyant scheme (undated, though one suspects no later than the 1850s) with its strange, gangly proportions took far greater liberties with historical precedents. The designer mixed in classical detailing, such as the rustication of the lowest storey with its over-pronounced batter, with archaeologically correct but rather exaggerated Romanesque detailing, such as the deep corbel table running below the cornice. The arch piercing the lowermost storey has the strange blocking already encountered at Streatham and seems to be carried on clustered pilaster strips. How the brightly patterned surface of the pyramidal spire was intended to be achieved – glazed tiles or some kind of painted metal surface? – is a mystery. The bell tower was finally constructed in 1891-1892 to a design by Charles Harrison Townsend.

An equally capricious interpretation of mid-Victorian Italianate is in evidence in two perspectives held in the RIBA collection depicting designs for what appear to be large suburban villas. Both are asymmetrical and picturesquely composed with low towers, and both stand on peculiar flared and rusticated plinths reminiscent of the Ennismore Gardens campanile. In this one, the tower turns octagonal at first-floor level and the transformation is echoed by the chamfered corner of the adjacent return, from which a chimney breast emerges. In another, which boats a handsome conservatory, the attic spaces are lit by bizarre tiny windows which pierce the cornice between the brackets supporting the eaves. Nothing is currently known of either scheme and it is possible that neither was executed. But the wilful interpretation of the style is consistent with ‘The Limes’, a mansion built in 1851 on a site just off Wood Lane on the east side of Stanmore in Middlesex. The garden front is relatively conventional, but the entrance front is nothing if not original, with its off-centre porch, the adjacent bizarrely shaped chimney breast, eccentrically disposed fenestration (note the long row of small arched windows at ground-floor level) and strange forms breaking through the wall surface.

A design of 1853 for the shop of Breidenbach, a firm of perfumers and toilet soap makers based at 157B New Bond Street, shows how Roumieu’s Italianate style could lend itself effectively to interior design. No. 147 Hornsey Road, a substantial house of 1860, is tentatively attributed to Roumieu (erroneously stated as still being in partnership with Gough) in the list description, but is relatively sedate compared to works such as The Limes, with a symmetrical entrance front. Latterly used as the vicarage of Emmanuel Church, built over part of the grounds in 1884, on the 1870-1871 1:1,056 Ordnance Survey it is called ‘Tyrolese Cottage’.

Roumieu the Rogue Goth

In 1856, Roumieu restored the church of St Mary in Kensworth (formerly Hertfordshire, transferred to Bedfordshire in 1897), a largely Norman two-cell building with a later medieval west tower. Little is known of the scheme, which does not seem to be documented, but it evidently involved reroofing the nave, signalled by the patterns worked into the slate covering externally and the unusual roof structure internally, with diagonal braces running from the purlins to the arched braces and wall plates. All that is stridently High Victorian, but the stables that he added to Franks Hall in Horton Kirby near Swanley in Kent as part of his remodelling in 1860-1861 are relatively tame neo-Tudor. The additions to the late Elizabethan main house, such as the new staircase, are stylistically deferential to the older fabric. It seems that Roumieu did not adopt Gothic in earnest until well into the decade and the change in direction would seem to be marked by St Michael’s, Bingfield Street in Barnsbury, located a little to the north of King’s Cross station, established as a daughter church of St Andrew’s, Thornhill Square. Built in 1863-1864, it was a typical High Victorian town church, built of brick and incorporating vividly striped constructional polychromy in the window heads and arches of the nave arcades. There were lean-to aisles and a tower was evidently intended at the west end of that on the south side. The church does not survive, having been demolished in the early 1980s following redundancy in 1973.

Many of the devices used at St Michael’s were stock-in-trade of any architect of the time and, apart from some wilful touches in the detailing, the design was not especially memorable. But it set the scene for a series of more powerful statements, the first of which was St Mark’s, Broadwater Down, a suburb on the southern edge of Tunbridge Wells, built in 1864-1866 at the expense of the Earl of Abergavenny. In some respects it is a typical High Victorian Middle-Pointed church for an affluent suburb, but the exterior is full of idiosyncratic touches and this reaches its apogee in the extraordinary steeple. The middle stages of the tower are lit by sinister-looking pointed slits and sound is emitted from the belfry through rows of circular, oval and triangular holes. As much as possible of the wall surface between the corner buttresses is broken up into a restless array of steeply pitched set-offs and advancing and receding planes. Starting from the peak of the gable over the main entrance, a strange, mullion-like form runs the height of and bisects the elevation, going through all manner of geometrical transformations and turning half-way up into an attached shaft that itself is broken by a clock face carried on an angel corbel. It emerges at the top through the surface of the base of the spire as a peculiar, lucarne-like form. The grand interior is full of over-ripe foliate carving but, despite some inventive detailing, is not as strongly personal as the tower. Roumieu designed a substantial vicarage located on St Mark’s Road to the south of church. Whether the stable block was executed in accordance with the design held by the RIBA is unclear; at any rate, it seems to have been much altered in the 20th century.

St Mark’s was followed by the French Hospital on Victoria Park Road in south Hackney, built in 1864-1865. The name is slightly misleading – it was a hospital not in the modern but in the medieval sense. It owed its inception to a Huguenot by the name of Gastigny, who on his death in 1708 bequeathed £1,000 towards the foundation of an institution to care for elderly, sick and impoverished French Protestants who had settled in London following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. This eventually opened in 1718 at a site on what became Bath Street on the northern edge of the City, then in open country, and it was known by London Huguenots as La Providence. As the community got itself on a surer footing, the number of patients and inmates dwindled, but the situation changed after Waterloo, when a wave of cheap imports threatened the silk-weaving industry in which many Huguenots were engaged. The directors of the French Hospital (Roumieu himself was among them, also holding the post of surveyor to its estate) decided to capitalise on the commercial value of the Bath Street site, which was now in a heavily built-up area, and used the income from the leases on it to purchase 3¼ acres near Victoria Park in what were then semi-rural surroundings. The site had originally formed part of the grounds of a large house, and the new premises of the French Hospital bore more than a passing resemblance to a stately home, being set back from the road in spacious grounds with a lodge house at the main entrance.

The plan was roughly cruciform, with a long spine corridor running east-west, which rose the full height of the building, had galleries at first-floor level and was top-lit. On the ground floor it ran from a board-room at the west end to a chapel at the east end. In the centre, an entrance hall on the south side and a staircase on the north side communicated with it. The basement was occupied by service accommodation, while the day rooms, library, dining hall and other function rooms were located on the ground floor. Most of the first floor consisted of four-bed dormitories, with more extensive quarters for the steward occupying the prominent polygonal tower which rose above the main entrance.

Stylistically, the design mixed a number of influences. In the vertical emphasis, asymmetry, angular modelling of the forms and busy skyline, it was essentially High Victorian Gothic in spirit; explicitly so in the case of the chapel and certain aspects of detailing elsewhere, such as the portal of the main entrance, the roof dormers, the flèche rising from the ridge of the roof of the main tower, the cast-iron cresting and finials. But the diapering of the brickwork and mullion and transom windows owed more to the neo-Tudor of designs such as the St Pancras School. Some commentators, such as the author of the report on the new building that appeared in The Builder of 2nd June 1866 and the author of the list description, have wanted to see French influence in the design; certainly features such as the first-floor windows of the main front with their transverse gables or the acutely steeply pitched roofs have been borrowed from late French Gothic of the early 16th century, when it was already passing into Renaissance. The French Hospital sold the site in the late 1940s when it moved out to Rochester and it was acquired by a Roman Catholic order of nuns, who turned the building into a girls’ convent school. It later became a Roman Catholic secondary school and then eventually the Mossbourne Academy in 2014. The building survives relatively well inside and out, though the patterned slate covering of the roofs has long gone, the chimneys have been truncated, much of the decorative ironwork lost and the lodge building was reconstructed in simplified form in 1934, when part of the site was acquired for residential development by London County Council.

Yet despite the purported French influence, a number of devices in evidence at the French Hospital, such as the swept eaves, seem to have been more general Roumieu trademarks and they crop up elsewhere, such as in this design in the RIBA collection for a house in Bushey, to the southeast of Watford. Indeed, he seems to have used his High Victorian manner extensively for large suburban villas, such as ‘The Priory’ on Glencairn Road, just off The Ridgway in Wimbledon, built in 1866. It was well suited to irregular, rambling compositions and picturesque detailing, such as deep eaves and bargeboards. In these designs there are reminiscences of domestic architecture in the neo-Tudor and cottage orné styles that had been current several decades earlier. But for what – as far as is currently known – was his most important private house, Hillside on Brookshill in Harrow Weald, Roumieu adopted a distinctly strident and uncompromising manner. It was commissioned by Thomas Francis Blackwell (1838-1907), a director in the Crosse and Blackwell firm producing preserved foods and table sauces, and it was built for his daughter-in-law and her family.

The Blackwell connection was an important one for Roumieu: his obituary in The Builder records that he died at The Cedars in Harrow Weald, ‘the residence of his brother-in-law’. This was probably the elder Thomas Blackwell (1804-1880), who with Edmund Crosse (1804-1862) had in 1830 purchased the company originally known as West and Wyatt, where they had both been apprentices, and renamed it after themselves. In 1834, Blackwell married Ann Bernasconi of the Clock House, located just to the south of the Uxbridge Road between Harrow Weald and Hatch End, where he took up residence. He subsequently renamed the property and engaged Roumieu to remodel and enlarge it. The commission is recorded in Roumieu’s obituary in The Builder, although exactly what he did and when is currently unclear, and the building does not survive – it was demolished in the late 1950s after the estate was bought by London County Council for a development of council housing. Given the connection, it would not be surprising to find that Roumieu designed the monument to Edmund Crosse and his wife and the Blackwell family tomb in the churchyard of All Saints, Harrow Weald. Certainly it is plausible on stylistic grounds, although it wants documentary proof.

Hillside, located about half a mile away to the northeast of The Cedars, fared little better, also being disposed of by the Blackwells in the late 1950s. It was badly damaged by fire at some point between then and 1969, when it was recorded in a series of melancholy photographs in the collection of the London Metropolitan Archive. The house was a curious blend of neo-Jacobean motifs – such as the numerous Dutch gables and symmetrical composition of three of the bays of the garden front – with thoroughly High Victorian motifs in a muscular Rogue Gothic manner. The brickwork was banded, diapered and notched throughout. The entrance porch was set at an angle in the return of one of the rear wings, with a tiny quarter-turn oriel projecting above and a larger circular tower with a candle-snuffer roof to one side emerging from the end wall of the main garden front range. Some of the windows consisted of plate tracery, while the garden front was fenestrated with extraordinary two-storey bay windows, the upper storeys of which were jettied outwards like oriel windows. The ruins became progressively more dilapidated and overgrown until the site was redeveloped in the 2010s, with the by then scant remains of the old house being incorporated into a new block of flats. The stable block and coach house survives intact, however, and is listed at Grade II.

Hillside is the only building in Roumieu’s career that quite stands comparison with his most celebrated work, Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap. That was commissioned by Hill, Evans & Co – the vinegar-brewing concern in Worcester of which Edward Bickerton Evans of Whitbourne Hall was one of the proprietors – to replace their old London premises on Martin Lane, which had had to be demolished for the construction of the District Line. Given the demand for vinegar in the production of its numerous lines of pickles, it seems likely that Crosse and Blackwell had a close commercial relationship with Hill, Evans & Co, and one infers that the commission came about as a result of Roumieu’s marriage into the family. As explained in a lengthy preamble to the report on the new building in The Builder of 10th October 1868, the site was reputed to be that once occupied by Mistress Quickly’s Boar’s Head Tavern, which features prominently in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1. This was commemorated by a carved roundel of a boar’s head on the tympanum of the central window of the second floor. The building had to provide not only offices for the company, but also storage space, which The Builder explained was accommodated in two tiers of cellars below street level. How the remainder was arranged internally is not quite clear. The classic arrangement during the period for commercial buildings such as this was for the main street entrance to be located in the centre with the stairwell rising out of it, but here the corresponding position is occupied by what appears to be a vehicle entrance, filled with elaborate wrought iron gates. The illustration accompanying The Builder’s article shows doorways at street level reached by small flights of steps in both halves of the building, an arrangement altered in later years when the ground-floor accommodation was converted to shops.

The report noted that ‘As the rooms were intended for offices in a narrow street in a city having a dull atmosphere, large openings for light become a necessity, and have been provided’. It stated that moulded ‘specials’ had been used for the brick arches (presumably those at third-floor and attic level) and that Tisbury stone had been used for the dressings. The carving was executed by sculptors Frampton and Williamson ‘from drawings by the architect, and is executed cleverly. Messrs Simpson did the external and internal tilework, and Messrs Peard and Jackson most of the ornamental ironwork, the whole of which was designed by the architect for this building’. The value of the contract, which had been awarded to Brown and Robinson, was given as £8,170. But despite the prolixity of the report, which expounded at some length on the output of the contemporary vinegar industry, The Builder was terse about the stylistic treatment of the building, describing it as ‘the Gothic of the south of France, with a little Venetian impress; and the design, if a little overdone, may be considered picturesque and original’.

The design of Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap embodies several enduring preoccupations in Roumieu’s work, such as the love of attenuated forms and narrow subdivisions of the wall surface. A heightened interest in texture is also thrown into the mix, with cogged brickwork used for the tympana of the windows at attic level and cornice running below. The surfaces of the set-offs forming the sills of the windows at second-floor level have a ‘negative fish-scale’ pattern, executed in shallow relief. Even the intrados of each trefoil-headed opening of the canopies in front of them are adorned with diaper-work, while the lintel behind has a strip of foliate ornament. Not for the first time in a High Victorian building, the profusion and exuberance of the ornament give the architecture a temperamental kinship with the High Baroque.

With Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap, Roumieu pushed his interpretation of High Victorian Gothic to an extreme. The danger with this line of development is that it potentially leads up a blind alley. Once replicated, such an aesthetic compromises its own individuality, and shock tactics can only be deployed to full effect once. But something of it re-emerged at least once, this time on a slightly smaller scale, with another commission for commercial properties in the City of London at Nos. 48-49 Cheapside, located on the south side of the street and a little to the west of the church of St Mary-le-Bow. Here, Roumieu was engaged to design new premises at addresses which had previously been occupied by two houses thrown up in haste following the Great Fire of 1666, as explained in The Builder of 26th September 1874. As with the report of six years earlier on Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap, the report holds forth at great length on the history of the site and its environs at the expense of its ostensible subject. It does, however, disclose that initially Roumieu ‘prepared designs of a Medieval character for both of the houses, varying, however, in design, but still in unison so as to form one composition. That prepared for No. 48 has been carried out with very little variation, but Messrs. Lake & Turner preferring the Renaissance style, Mr Roumieu, in conformity with their wishes, prepared a second design for No. 49’.

Many of the devices incorporated in the street façade of No. 48, such as the liberal use of patterned and textured surfaces, were familiar from Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap, although the three-centred arches with ogee curves above rising to decorative finials introduced a late Gothic flavour. The fourth floor and attic under a steeply pitched roof, its elevation centred on an oriel aligned with the apex of the arch beneath, almost formed a self-contained composition. At No. 49, the division of the elevation into narrow vertical units, with a profusion of advanced and receding planes and chamfered and faceted surfaces, was effectively translated into Italianate, for which Roumieu had prepared the ground with his idiosyncratic essays in the style of the late 1840s and early 1850s. At No. 48, the carving was once again the work of Mr Frampton, apart from the large figure of King David holding a harp at third-floor level, which was executed by a Mr Wyon – probably Edward William Wyon (1811-1885), who came from a well-established family firm of sculptors, engravers and medallists. The same Wyon executed the figure of Plenty sitting on the extrados of the segmental arch above the shopfront of No. 49 and some of the roundels, again after ‘small sketches by the architect’. The remainder of the carved detail adorning the façade of No. 49 was by a Mr Kelsey, perhaps Charles J. Samuel Kelsey, an architectural sculptor who also came from a London-based family firm. At some point no later than 1931, No. 48 was rather brutally de-Victorianised with the complete loss of the detail enclosed by the Gothic arch, including the figure of King David. Both buildings were gutted during the Blitz, when the neighbourhood was very badly damaged, and the ruins cleared away soon afterwards.

Roumieu designed a number of other commercial buildings in the City of London and its environs, most of which – assuming they have not all disappeared unrecorded – await discovery and study. So far, the only one in the City proper to have come to light is Victoria Wharf on Upper Thames Street, noted in The Builder’s obituary, which stood immediately to the east of Blackfriars railway bridge adjacent to Puddle Dock. Pre-war aerial photographs show a typical Thameside warehouse, five storeys in height and three bays wide, with some sort of ornamental trimmings to the upper part of the river front. Not much more can be deduced and, after sustaining bomb damage, it was demolished for redevelopment during the late 1940s or 1950s. Right at the end of his life, Roumieu designed a couple of commercial premises for Crosse and Blackwell, both of them located on Crown Street in Soho, which subsequently became the northern half of Charing Cross Road between Cambridge Circus and New Oxford Street. At No. 111, what was in effect a depot for delivery vehicles went up in 1875-1876 on a site on the western side formerly occupied by the Plough Inn. As The Builder noted in its issue of 15th April 1876, the rising cost of land meant that ‘London stables are following the example set by London houses of shooting up vertically, instead of spreading horizontally’. The ground floor was mostly given over to bays for the delivery vans, of which there were 18, with storage for fodder, a tack room, a dung yard and so on. The stables proper were on the first floor, 13ft (4m) above ground level, and access was provided by two ramps. Here, there were stalls for 35 horses, a loose box for a sick horse and ancillary facilities. The second floor of the range along the street front was occupied by living quarters for the stablemen, arranged ‘with windows looking into the open space above the stable, so that a view can be taken at any moment of the whole of the stables on the upper floor’. There was a tank for feeding the water troughs, hosing down the stalls and supplying the fire hydrants. Though the ground-floor storage bays and first-floor stalls were arranged around a central atrium, this was not open to the sky, being spanned by king post and queen post trusses resting on intermediate cast-iron columns and incorporating a monitor roof to provide top-lighting.

The street front was treated in a thick-set neo-Romanesque style, quite unlike anything else in Roumieu’s output, with the fenestration deliberately small to emphasise the massiveness of the wall surface. This was constructed of red brick, incorporating – perhaps for the broad decorative band at first-floor level – Pether’s ornamental bricks. The dressings were of stone and the carving was again the work of Frampton. In the 1920s, Crosse and Blackwell wound up all its operations on the Charing Cross Road and the stables were demolished for redevelopment. Roumieu also designed a warehouse for the company at Nos. 151-155 on the western side just short of the junction with New Oxford Street. It was a substantial structure which eventually rose to a height of 76ft (23m), but construction, which began in 1877, had to be suspended after threats of legal action from the owners of surrounding properties over the loss of light and air. It did not recommence until 1885 when Crown Street was widened to the east as part of the construction of Charing Cross Road and the problem had solved itself. After changing hands, the building was altered beyond all recognition externally in 1925-1926, then the site was cleared in 2009-2010 for the construction of Crossrail.

Succession and conclusion

On Roumieu’s death in 1877, his practice was taken over by his son, Reginald St Aubyn Roumieu (1854-1921). He had trained for six years with his father, but, evidently still green, decided to go into partnership with the older Thomas Kesteven Hill. This arrangement lasted for only two years before being curtailed by Hill’s death. In c. 1880, he went into partnership with Alfred Aitchinson (d. 1914), with whom he oversaw the completion of Nos. 151-155 Charing Cross Road. Gough’s practice, it might be noted briefly, was also continued after his death by his son, Hugh Roumieu Gough (1843-1904) evidently named in honour of his erstwhile business partner. The younger Gough was one of the numerous collaborators of J.P. Seddon, working with him on the design for St Paul’s Hammersmith, rebuilt on a grand scale in 1882-1891. He was also sole designer of the church of St Cuthbert, Philbeach Gardens, providing the grand shell built in 1884-1887 that was later much embellished internally by Ernest Geldart and William Bainbridge Reynolds.

Roumieu’s work has been seen as epitomising High Victorianism, yet it also poses searching questions about its provenance and nature. Firstly, it begs the question of where exactly Victorian architecture begins. His earliest known work with Gough was erected around the time that Victoria acceded to the throne. Yet this cut-off point is largely arbitrary where architectural history is concerned – fashions do not, after all, always proceed in lockstep with politics. Both architects had been schooled in the traditions of the long 18th century, and inhabited a milieu from which many of the influences which would shape High Victorianism were absent. Roumieu involved himself little in ecclesiastical architecture and seems not to have participated in competitions for major public buildings, two areas where debate over architectural theory and aesthetic propriety raged most fiercely. The sort of licence in the use of historical motifs exemplified by the steeple of St Peter’s in Islington is hardly unusual for the first half of the 19th century. It was a hangover from Georgian Gothick, which was gradually purged from architecture by the growing concern with archaeological precedent and the high-minded censure of Pugin, Ruskin and The Ecclesiologist. Yet when one compares the unexecuted design for the Milner Square church with St Mark’s, North Audley Street, a marked difference in feeling between late Georgian and early Victorian architecture becomes apparent, which is more difficult to explain away. What are we to make of this?

Conceivably, this in fact has nothing to do with the Zeitgeist and everything to do with personal character – the prevalence of nature over nurture, in other words. Licence and the impulse to distort, to exaggerate, to carry everything to extremes informed all of Roumieu’s design. Virtually every stylistic influence brought to bear on him by changing fashions – Greek Revival, Italianate, neo-Norman – is refracted through a distorting lens. When one leaves aside 20th century constructs and imposed associations, one sees that Nos 33-35 Eastcheap embodies a common thread in his Roumieu’s aesthetic that runs all the way back to the Islington Literary and Scientific Institute – the preoccupation with subdividing the elevation into tall, narrow units, with endlessly varying the modelling of the wall to eliminate any expanse of flat surface and the fascination with layered planes. The nervous, restless character of his work is a constant.

Goodhart-Rendel was perhaps misguided in grouping in Roumieu with the Young Turks of the 1860s, such as E. Bassett Keeling and Joseph Peacock, not least because Nos. 33-35 Eastcheap comes from the final decade of its architect’s career. The Rogue Gothic buildings are not wholly representative of Roumieu’s output as a whole, and indeed to some extent a swansong. Yet Goodhart-Rendel was right in according to him the status of rogue architect in a more general sense. The epithet has been so frequently applied to the practitioners of the more eccentric brands of High Victorianism of the 1860s that it tends to be forgotten that the chronological scope of the RIBA lecture of 1949 for which he coined the term embraced a period running all the way from the 1840s to the 1890s. The common factor, which for him distinguished every figure featured in it, was a tendency to stay apart from the herd, powerful individualism manifesting itself in highly personal design that was neither emulated by contemporaries nor inspired a school among architects of a younger generation. In the case of some of the rogues, such as Alexander Thomson, the latter was inevitable: they persisted with an idiom that was out of fashion by the end of their career, and thus represent an isolated line of development which was fated to be curtailed by their death. Others, such as Bassett Keeling and Peacock, toned down their style in later life, ceding originality to respectability and conventionality. But in the case of Roumieu, the matter is nothing like as straightforward. Though he reinvented himself more than once, his personality remained inimitable from first to last. Though he had a partner and a pupil, neither went on to produce anything that stands comparison with his work. There is, perhaps, no greater accolade for a rogue.

4 thoughts on “Robert Lewis Roumieu: progressive or prankster?”