The internet has changed the process of writing architectural history beyond all recognition. Information that just twenty years ago would have required lengthy and arduous research to track down can now be obtained with a few clicks. The amount of material which has been digitalised and placed within the public domain is truly staggering. It is now possible to produce a reasonably authoritative, well illustrated account of the life and work of a Victorian architect through desktop research alone. In many ways, this blog is a testimony to that, since numerous posts were written during the second and third COVID lockdowns in the United Kingdom, when all libraries and archives were closed to the public and opportunities to visit historic sites severely restricted. All the same, sooner or later one discovers gaps in one’s knowledge that cannot be filled so easily – and not through archival or field research, either. The great merit of the blog format, especially when used in conjunction with social media, is not just that it makes it easier to share the fruits of one’s research than ever before, but that it greatly expands one’s ability to elicit information.

For that reason, when I started ‘Less Eminent Victorians’, I hoped that it might flush out information that had yet to come to the attention of scholars. Late last year it did just that – and to a degree that exceeded my wildest expectations. My second post for the blog dealt with John Croft, whose extravagantly original St John the Baptist at Lower Shuckburgh in southeast Warwickshire has long been a destination for churchcrawlers. Yet other than a church at Cold Hanworth in Lincolnshire, nothing in a very meagre works list came anywhere near to it in architectural interest, leading me to wonder whether both buildings might be no more than a flash in the pan. I had no reason to reconsider my view until I was contacted through the blog back in November 2021 by a Laura Amalir, who introduced herself with the words, ‘I have just chanced upon the article about the architect John Croft. He was my great-great grandfather and we have quite a bit of archive material that may be of interest, not to mention a great many paintings by his son, Arthur’. This intrigued me straight away and we began corresponding.

To cut a long story short, in February the opportunity finally arose to inspect this material for myself and what I saw so impressed me that it deserves to be published here – not only for the light that it sheds on what I already knew of Croft’s life and work, but also for its huge intrinsic value. It needs to be said right away that the quantity of papers, drawings and paintings is very substantial: simply cataloguing them all would be a major task, and a proper scholarly analysis would suffice for a Master’s thesis at the very least. Laura could not have been more accommodating, but the few hours that I was able to spend looking at the family archive was insufficient to do more than get a sense of what awaits proper investigation. What follows is intended to convey that – and also to afford readers the same pleasure and delight that I derived from sampling Croft’s rich, colourful and highly imaginative visual world.

Biographical discoveries

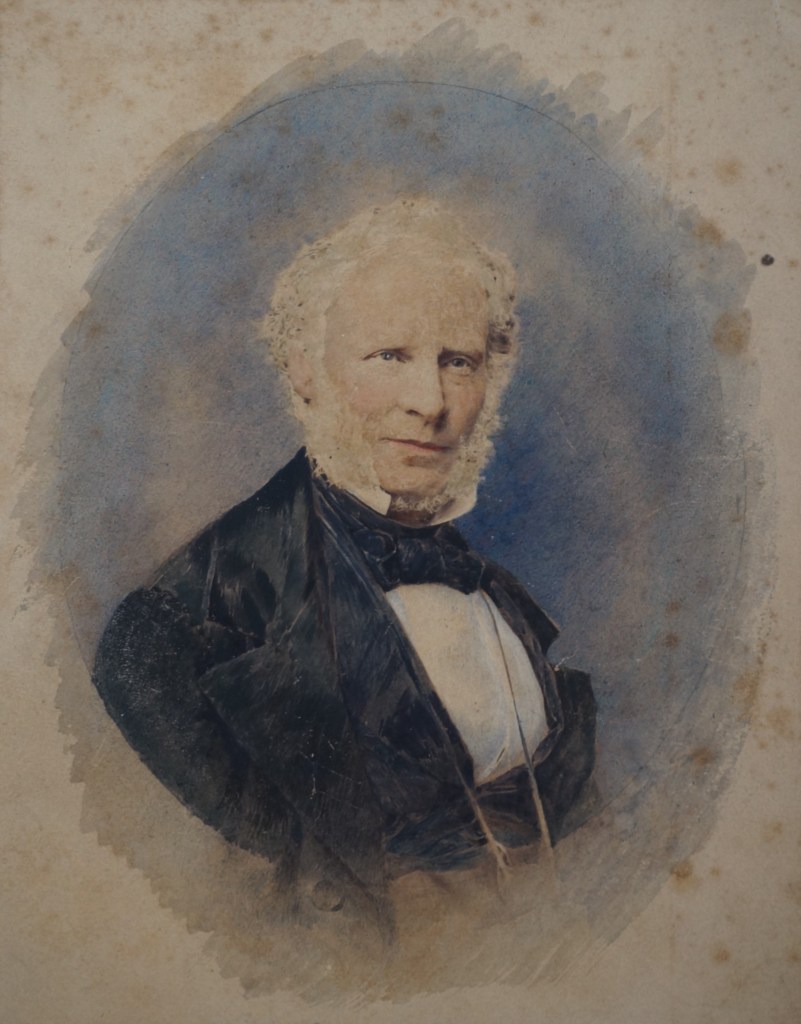

I entitled my first post ‘John Croft: the most mysterious rogue of all?’ because of the dearth of biographical information about its subject. Thanks to the formidable research skills of Peter C.W. Taylor – a good friend of Less Eminent Victorians – I was at least able to supplement some of the basic data that has eluded previous commentators, but the Croft papers go far beyond this in fleshing out a portrait of someone who was hitherto a very shadowy figure. A document among the papers compiled by a family member long after Croft’s death states that he was born on 19th April 1800 (corroborated by what Peter had deduced from the census data) and died on 14th March 1885. He was buried in Paddington Cemetery. And, excitingly, we can put not only definite dates of birth and death but also, at long last, a face to the name, since the family archive includes two watercolour portraits of Croft in later life. They are unsigned, but it is a reasonable guess that they were executed by his daughter Marian, who was reputedly a skilled miniaturist.

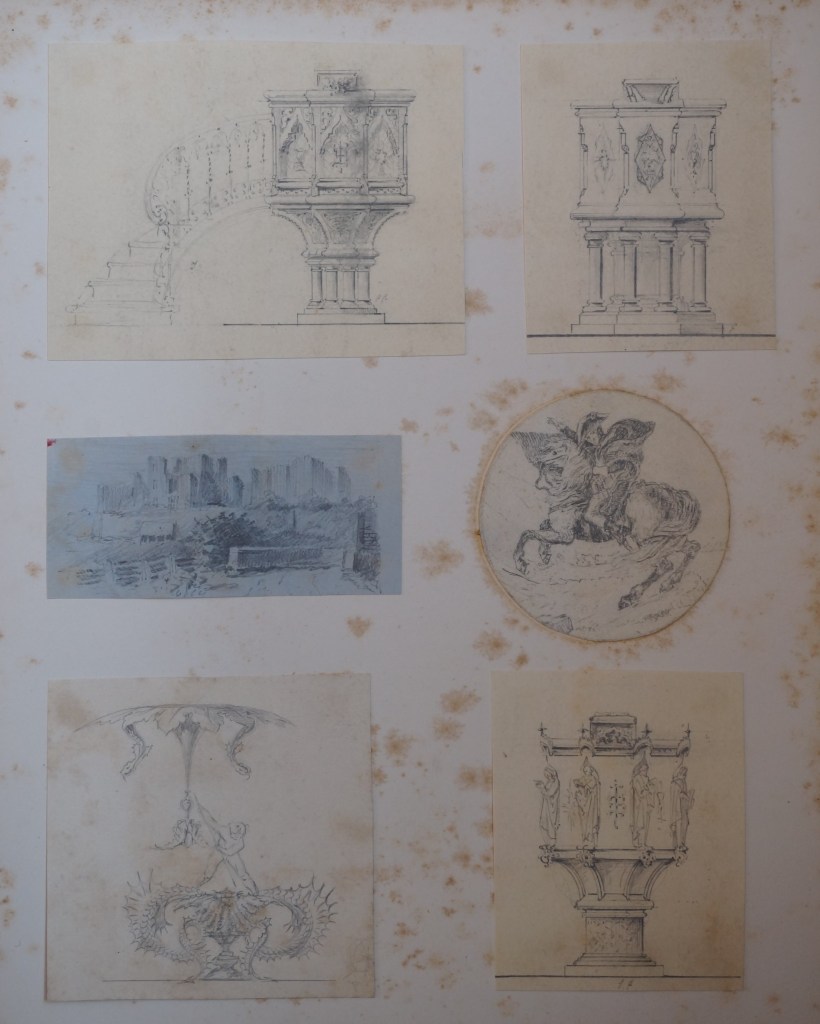

But perhaps the biggest revelation is that Croft’s professional career began in a very different and wholly unexpected field. He initially trained not as an architect, but as an ivory carver and attained some accomplishment, showing pieces at the Royal Academy in 1829 and 1830, and produced a medallion with a profile portrait of George IV forming the lid of a snuff box now held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, in whose catalogue it is unattributed. The family archive includes what seems to be a photographic reproduction of a self-portrait in the form of a similar medallion, as well as two portrait busts of his wife, Emma. According to Laura Amalir, his granddaughter (who was her great aunt) claimed that he abandoned ivory carving after breaking his wrist, which one surmises happened at some point in the 1840s. Peter’s discovery that Croft acted as clerk of works for the construction of the Warwick County Lunatic Asylum, completed in 1850 (confirmed by a number of documents relating to this project, such as estimates from sub-contractors all inscribed ‘For Mr Croft’), suggests that architecture may have been a second career and not one that he had been pursuing in tandem. Perhaps significantly, it was around this time that Croft became a freemason, joining the Lodge of Unity in Warwick, and the family archive includes his apron. Yet whatever more detailed research may or may not reveal, it is clear that architecture – and predominantly the heritage of the European Middle Ages – was an enduring passion, as demonstrated by the large number of pencil and watercolour views by Croft of Gothic buildings in the family archive.

Croft the architectural illustrator

They are all executed to a high standard and, though decidedly Romantic in spirit – interior views predominate, and he revels in dramatic effects of light and shade – are by no means impressionistic. They evidence profound understanding of the architecture depicted, and the pencil underdrawing demonstrates that the perspective and ornament were all carefully worked out before the wash was applied. Westminster Abbey seems to have held a particular fascination for Croft and there are numerous views of the interior, including even one featuring a pulpit of his own design, inscribed on the reverse ‘From the pulpit loud proclaim / Salvation in Christ Jesu’s name’. Given Croft’s Warwickshire connections, one is not surprised to find views of the great medieval town church of Holy Trinity in Coventry. But the subjects are not exclusively ancient and the archive includes a number of illustrations of buildings completed in Croft’s own lifetime – the Palace of Westminster and, less expectedly, the interior of G.E. Street’s St Saviour’s in Eastbourne, completed in 1867. Nor are they exclusively domestic, and there are exterior views of Rouen Cathedral in Normandy, St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, even the Red Fort in Delhi.

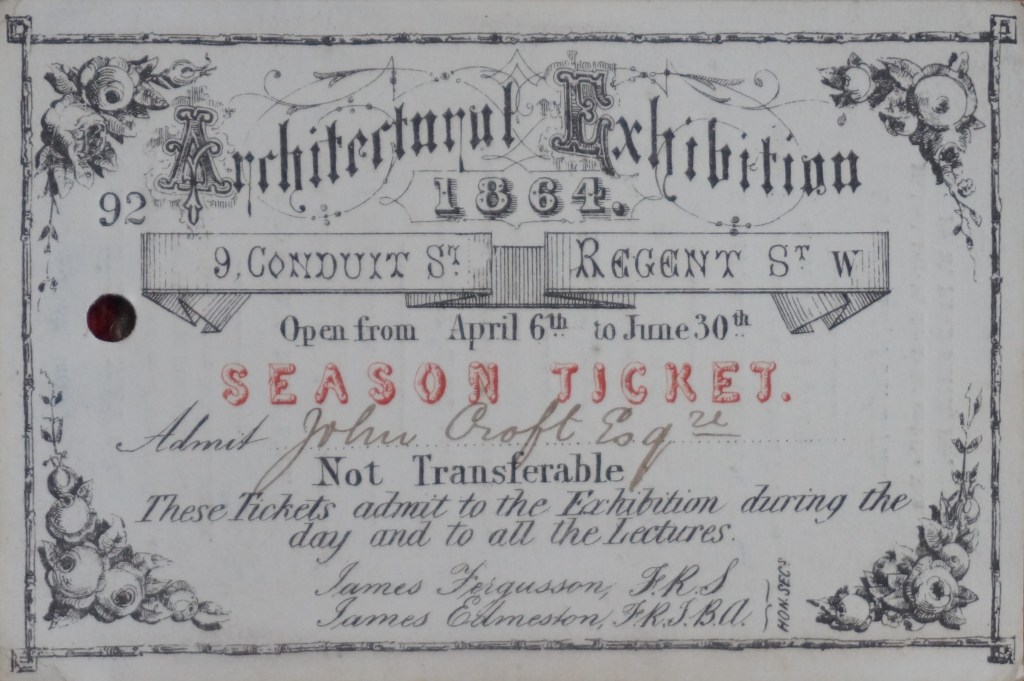

But to surmise from this that Croft had undertaken some sort of grand tour throughout Europe and perhaps even further afield along the lines of S.S. Teulon’s great expedition of 1841-1842 may be to jump to conclusions. The archive also includes an extensive collection of published engravings of famous works of architecture and Croft’s views may be based exclusively on these rather than field research. Tellingly, for example, the views of Rouen Cathedral show it still with the central spire destroyed by lightning in 1822. The purpose of the drawings is difficult to ascertain. According to Algernon Grave’s dictionary, Croft exhibited nothing at the Royal Academy after showing the two ivories. Evidently he was interested in the work of his peers, since the papers include three tickets to exhibitions, two of them Architectural Exhibitions from 1864 and 1869. But the only mention of Croft’s work discovered so far in literature of the time relates to a view of the interior of All Saints, Cold Hanworth in Lincolnshire, described briefly in a review of the 1864 Architectural Exhibition published in The Builder’s issue for 9th April of that year (there is no mention of him in that publication’s review of the 1869 show). If Croft had enough interest in promoting his architectural work to show views of it to a London audience, then why is his output not more extensive? If, instead, his interest lay in promoting himself as an architectural illustrator, then why did so many views executed to the standard of presentation drawings (in which he was reputedly helped by Arthur) and manifestly of saleable quality remain among his own effects? Or are these in fact exclusively the fruits of his leisure?

Built works and new discoveries

For the moment, one can do no more than speculate, but though the papers shed important light on Croft’s architectural career, much about it remains enigmatic. They do not much much expand the catalogue of known works and these, all told, do not equate to the sort of output that might have sustained a man with a large family over the course of a long life, even allowing for his late entry to the architectural profession. But, thanks to a couple of important finds among the papers, we do at least now know approximately when this happened. Material in the family archive allows Croft to be identified as the author of the comprehensive remodelling of St John the Baptist in Upper Shuckburgh, carried out in 1849-1855 according to Chris Pickford’s revision of the Warwickshire volume of The Buildings of England, published in 2016. The sources consulted for that edition recorded the name of the builder, the stonemason and the glazier but not, surprisingly, the architect. There are two highly finished presentation drawings of the church, depicting a general view of the interior looking east and differing essentially only in the treatment of the detailing of the double-hammerbeam roof.

Neither view is captioned and identification of the subject confounded the author until he was able to corroborate a hunch, thanks to a photograph provided by the Rev’d Gillian Roberts, priest-in-charge of the benefice that includes the church. St John’s is a ‘peculiar’, outside the jurisdiction of the diocese, and effectively a private estate chapel (it stands in the grounds of Shuckburgh Hall) where services can only be held at the invitation of the Lord of the Manor. Corroboration of Croft’s authorship is given by a pencil and wash illustration of the pulpit, discovered among the papers, which is captioned in the architect’s own hand. The work at Upper Shuckburgh gives the impression of having sprung from the head of an antiquarian with a slightly overheated imagination, but there is much about the adventurous handling of form of the pulpit and prodigious invention in the detailing of the roof that foreshadows what he went on to do at Lower Shuckburgh. If Croft was indeed involved with this project from the outset, that would suggest that he had established himself in independent practice before the County Asylum was finished.

Then there are three presentation drawings – all taken from the same southwestern viewpoint – of Birdingbury Hall, an originally early 17th century country house located in a small village about equidistant from Leamington Spa and Rugby. The building was damaged by a serious fire in 1859, which evidently necessitated major building work. Chris Pickford’s revision of Warwickshire does not identify the architect, but notes that the house was originally built by the Shuckburgh family, whose influence in the area perhaps accounts for the commission, and Croft is recorded as having been involved in remodelling the entrance hall of Shuckburgh Hall at the same date. Exactly what was done at Birdingbury and why Croft should have gone to the trouble of producing three versions of the design (they differ only in fine detail) awaits discovery through study of material in the family papers and close inspection of the surviving fabric. There is some mildly quirky detailing visible in the drawings, but nothing as strongly personal as the ecclesiastical work. St John the Baptist in Lower Shuckburgh is represented in the family archives by a handsome presentation view in pencil and wash of the chancel and a rather winsome watercolour sketch in pastel tones of the exterior, showing it in evening light and playing up as far as they will go the picturesque qualities of the building. There is a third view of the nave looking west, evidently intended to be a presentation drawing, which has got no further than the pencil underdrawing.

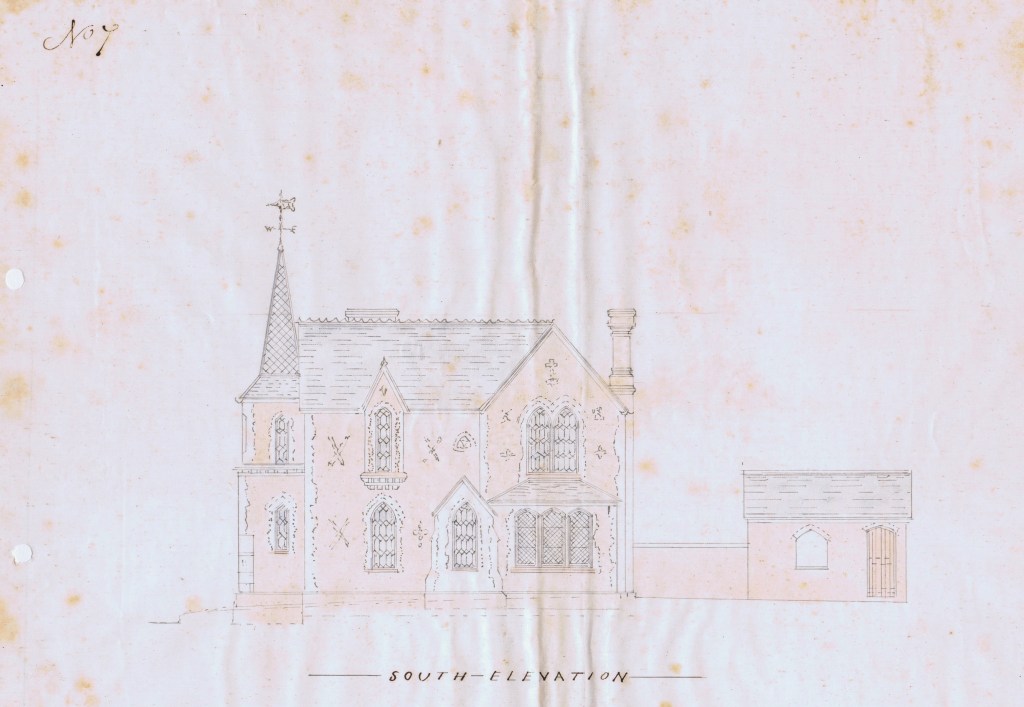

Two more Warwickshire commissions have been identified thanks to the family archive. It includes a full set of contract drawings for what was presumably the national school at Hampton-on-the-Hill, a small village located just to the west of the county town. They are all signed ‘John Croft Architect Warwick’ and, though they bear no date in his hand, one of the elevation drawings shows that ‘1854’ was to be laid in brick beneath the sills of the bay window of the schoolroom as part of a scheme of polychromatic brick patterning. In configuration, with the large block of the schoolroom offset by the more intricate massing of the schoolmaster’s house and its decidedly ecclesiastical overtones, it is a typical village school of the period. But whereas those were usually high-minded essays in earnest Puginian Middle-Pointed Gothic (see, for instance, the school at Foxearth featured in my post on Joseph Clarke), this design is self-consciously picturesque, more in the manner of the pre-Ecclesiological Goths and with features such as the decorative leadwork that are squarely in the cottage orné tradition. It has something about it of the contemporary schools in south London by Joseph Peacock, such as St John’s National Schools in Deptford, featured in my post on that architect. The school was built, but apparently in simplified form and, though still extant as a residential conversion, has been badly mutilated.

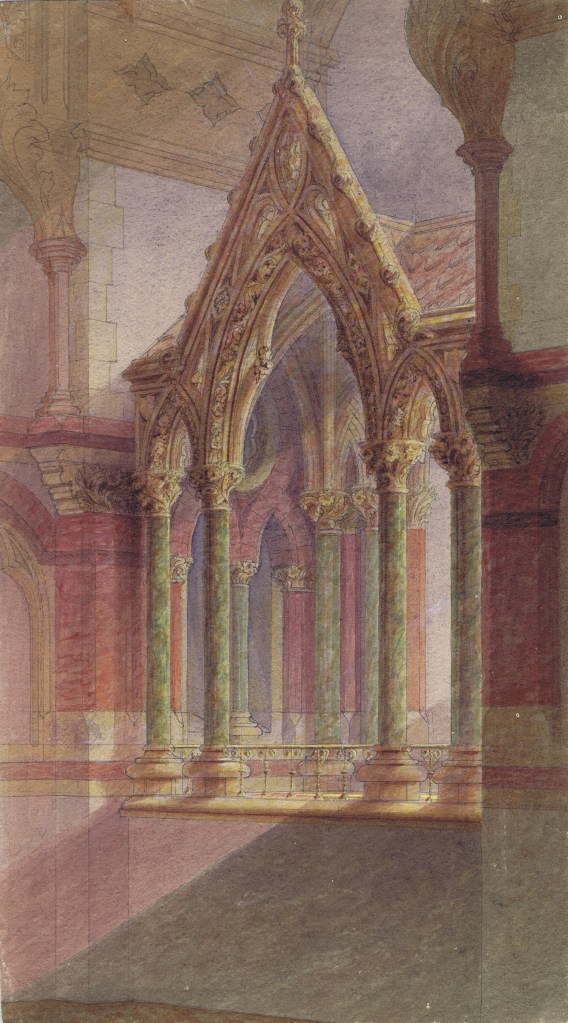

Material relating to known executed commissions outside Warwickshire among the papers includes a glut of views of St Laurence’s, Seale in Surrey – two of the interior (one very rough, the other depicting more or less what was built) and alternative versions of the exterior. These are conveyed by several drawings, which show how the central tower was raised in height, with a termination that starts off as a pyramidal roof with acutely pointed dormers, then turns into a typical Surrey splay-footed spire, and ends up as a pyramidal roof again – the form in which it appears today. There are three views of All Saints in Cold Hanworth, Lincolnshire. The one depicting the west end of the nave and baptistery is clearly that described in the report in The Builder of 9th April 1864 mentioned above, and is valuable for showing the full effect of the internal constructional polychromy, otherwise recorded only in black and white photographs of the building also discovered in the family papers. A second presentation drawing depicts an aedicule described on the reverse as ‘A design for a memorial to Col. Cracroft’, in whose memory the church was erected, and seems to have been intended for one of the openings on the north side of the chancel. As far as can be ascertained, it was not executed, and the Colonel was instead commemorated by an inscription on the wall. The third drawing is a watercolour sketch of the exterior, similar in character to that of St John’s in Upper Shuckburgh mentioned above.

Unexecuted designs for religious buildings

The material described above exhausts what can be positively identified as relating to Croft’s known work. It does not, however, exhaust the contents of the archives, for there is a large number of drawings and sketches depicting buildings with sufficient seriousness of intent to lead one to suppose that the architect cherished some hope that they might be executed – or, at any rate, executable. They are significant for what they reveal about the breadth of Croft’s interests and diversity of his architectural personality. Not surprisingly, ecclesiastical designs feature prominently. Lower Shuckburgh and Cold Hanworth whet the appetite for the sort of architecture that Croft might have produced when unconstrained by budgetary requirements or technical limitations, and in that respect the collection does not disappoint.

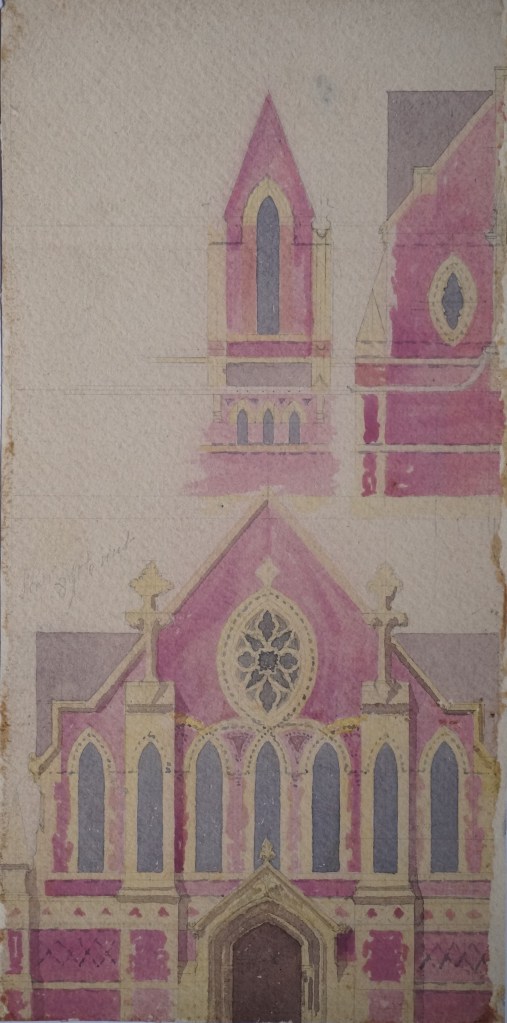

There is a spectacular design for what appears to be an urban or suburban parish church, clearly intended to seat several hundred worshippers. The plan form – cruciform, with a northwest tower and spire – is conventional enough. But how Croft elaborates that is a different matter altogether. The tracery is nominally curvilinear Decorated, but of quite fantastical form. That of the west window continues down to ground level to embrace a triple porch (disproportionately small compared to its counterpart on the north). The roof is pulled down low, so that the lateral windows rise into transverse gables, augmenting the effect of an already busy roofline, which bristles with pinnacles. The tower is a tour de force of sculptural invention, rising to a slender openwork spire and braced with corner flying buttresses – an arrangement similar enough to Roumieu and Gough’s St Peter’s, Davona Road in Islington to make one wonder if Croft had seen it (in later life he lived in the area, after all). Over the crossing is a intricate corona of filigree wrought iron.

Some of the devices tried here can be found in a design for a church depicted in a picturesque sylvan setting. At first sight it appears almost megalomaniacal, but when one begins to compute the height in relation to the doorway, one sees that it is monumental in its conception rather than the scale, which turns out to be almost toylike. Again, there is a busy roofline with pinnacles, transverse gables and two lanterns straddling the ridgeline, which are square at the base, but rise to a dome-like form. The slender spire is pierced with quatrefoil wind holes, a feature commonly encountered in medieval Breton architecture. There are short transepts, and an apse with flying buttresses is suggested. There is a good deal of exterior sculpture, hinting that this may be a Catholic church. The two-storey elevations suggest side chapels at ground level, but, read in conjunction with the longitudinal plan and axial west tower, also bring to mind early 19th century Anglican auditory churches, and indeed the whole design is fundamentally Georgian Gothick in spirit.

One deduces from a number of drawings in the collection that Croft was preoccupied with centrally-planned, top-lit polygonal spaces. Some, as will be discussed below, are pure fantasy, but two of the most memorable interior designs show an intriguing attempt to synthesise this with the longitudinal configuration of a cruciform basilica, perhaps inspired by Ely Cathedral. In one version, the side aisles of the nave are little more than passage aisles, which it is suggested are articulated externally with transverse gables. The aisles are divided off at ground level with traceried screens. A huge octagonal space to the east extends into them. This is effectively the chancel, since the apsidal sanctuary beyond is only one-bay deep. Note the detached columns at the angles of the octagon supporting the immense trusses, which rise to a central lantern. In the second version, the nave is treated like a Germanic hall church and the space is vaulted throughout. The treatment of the web of the vault suggests that this was intended to be constructed of ceramic pots like that at Lower Shuckburgh. In this version of the scheme, the vaulting and, hence, the spaces that it encloses, are much more tightly integrated and the whole is shown to be enclosed within a simple quadrilateral ground plan. The octagonal space rises to a drum glazed with stained glass instead of a lantern.

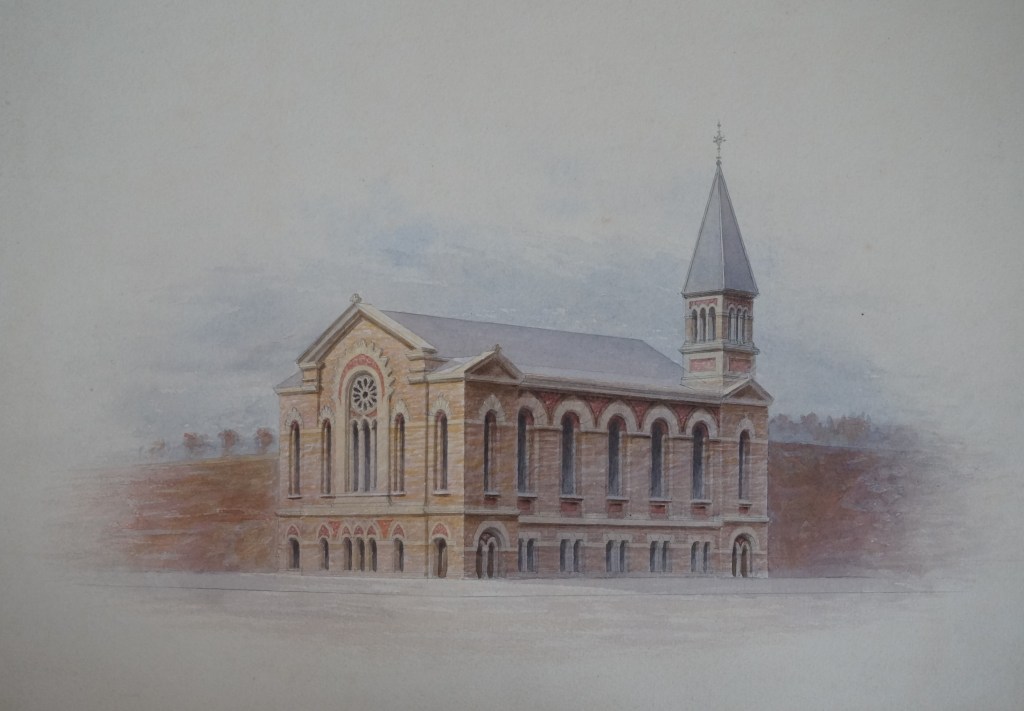

Not all the designs are quite so ambitious, nor are they all Gothic. There are a couple of tiny, but very deft concept sketches in pencil for churches with steeply pitched roofs and tall spires, the work of an architect who begins by thinking about the effects of light and shade that a building produces and how it appears from a distance in the landscape. There is a relatively sober scheme for an auditory church, perhaps for a nonconformist denomination, handled with aplomb in a Rundbogenstil manner. Only the placing of the Venetian-looking bell turret, perched on one of the corners like an afterthought, does not quite convince. There are fragments of a scheme for a church with a saddleback tower in a sort of Transitional Romanesque manner, evidently intended to be built of brick with stone dressings.

Croft could turn his hand to classicism, but only in one instance does he apply it to a sacred work – an arresting scheme for what is described on the reverse as a cemetery chapel. It follows the typical Victorian configuration of a central bell tower – really Italianate rather than classical – flanked by identical mortuary chapels, which one would expect to be for Nonconformists and Anglicans. These are satisfyingly compact domed forms, though the frothy ornament rather detracts from the tightness of the composition. Among the papers there is also a sketch described on the reverse in Croft’s hand as a ‘Roman [sic] cemetery chapel’ – a centrally-planned, domed space, abounding in rich colour and ornament, although looking more like a sculpture gallery with no obvious indicators of its religious function. Was the cemetery chapel scheme in fact intended to cater to Catholics rather than Nonconformists? At a push, it could just about be the interior of one of the domed volumes. A page of designs for pulpits in a strident High Victorian vein should also be mentioned. Comparison with the executed design for the pulpit at Upper Shuckburgh shows that these spring from the realm of the – theoretically – executable, but whether they are in fact more than sophisticated doodles is for now an open question.

Unexecuted designs for secular buildings

Though Croft handled secular commissions, nothing among them has yet been identified that could vie with, say, All Saints in Cold Hanworth as a comprehensive and characteristic statement of his architectural language. The vicarage at Lower Shuckburgh is a disappointment after the expectations raised by the church. And yet it is clear from an extensive series of drawings among the Croft papers that he was every bit as capable of exploiting domestic design as a vehicle for his prodigious imagination. For the most part these are sketch designs for large villas, usually described on the reverse as ‘a gentleman’s house’. The quality of the draughtsmanship varies from highly finished pen and wash presentation drawings to watercolour sketches. Nothing is currently known about the circumstances in which they appeared and whether any of them was executed, or at least stood any real chance of execution. The imposing scale and elaborate nature of the designs suggest that Croft had his eye on one-off commissions for wealthy clients as opposed to, say, grander suburban residential developments, but that must remain speculation for now.

Although there are distinctly Gothicising overtones in the asymmetrical compositions and vivid skylines, notably not one of them is Gothic. Instead, the style is a very busy, mannered and heavily ornamental Italianate. Some of the elevations are organised symmetrically, but Croft always does his best to throw them off balance with features such as prominent towers (sometimes housing a staircase), oriels, first-floor winter gardens, large bay windows and conservatories. The rooflines are always busy and expressive, with turrets, dormers, pavilion roofs, tall chimneys and decorative ironwork. The modelling of the forms is restless, with numerous advancing and receding planes, and the effect of breaking up the wall surface is accentuated by elongated, narrow and repetitious fenestration, sometimes organised as arcades with alternating blind and glazed openings. This gives these designs an affinity with Robert Lewis Roumieu’s Italianate villas of the late 1840s/early 1850s discussed in the post on that architect. Colour is all-important and the sketches suggest various different types of exterior polychromy – constructional in brick, perhaps sgraffito, perhaps painted, column shafts in polished red granite, stucco. Croft plays to his forte by exploiting the designs in a similar manner to his churches as discrete sculptural forms, abounding in picturesque accretions to maximise their visual appeal and form an eye-catcher in the landscape.

But there is also a smattering of other building types. One sketch depicts a lodge house in an Italianate style, apparently octagonal in plan and adjoined by sumptuous wrought iron gates to a driveway. Other than the drawings for Birdingbury Hall, it is the only item in the collection testifying to Croft’s interest in country house work. There are also highly finished presentation drawings for commercial buildings in a florid Second Empire style. One is a perspective view of a block that seems to be intended to form part of a quadrant, with lavish shopfronts faced in marble and incorporating arcades at ground-floor level and residential storeys above incorporating statuary. It looks as though it might have been intended to replace part of Nash’s Oxford Circus.

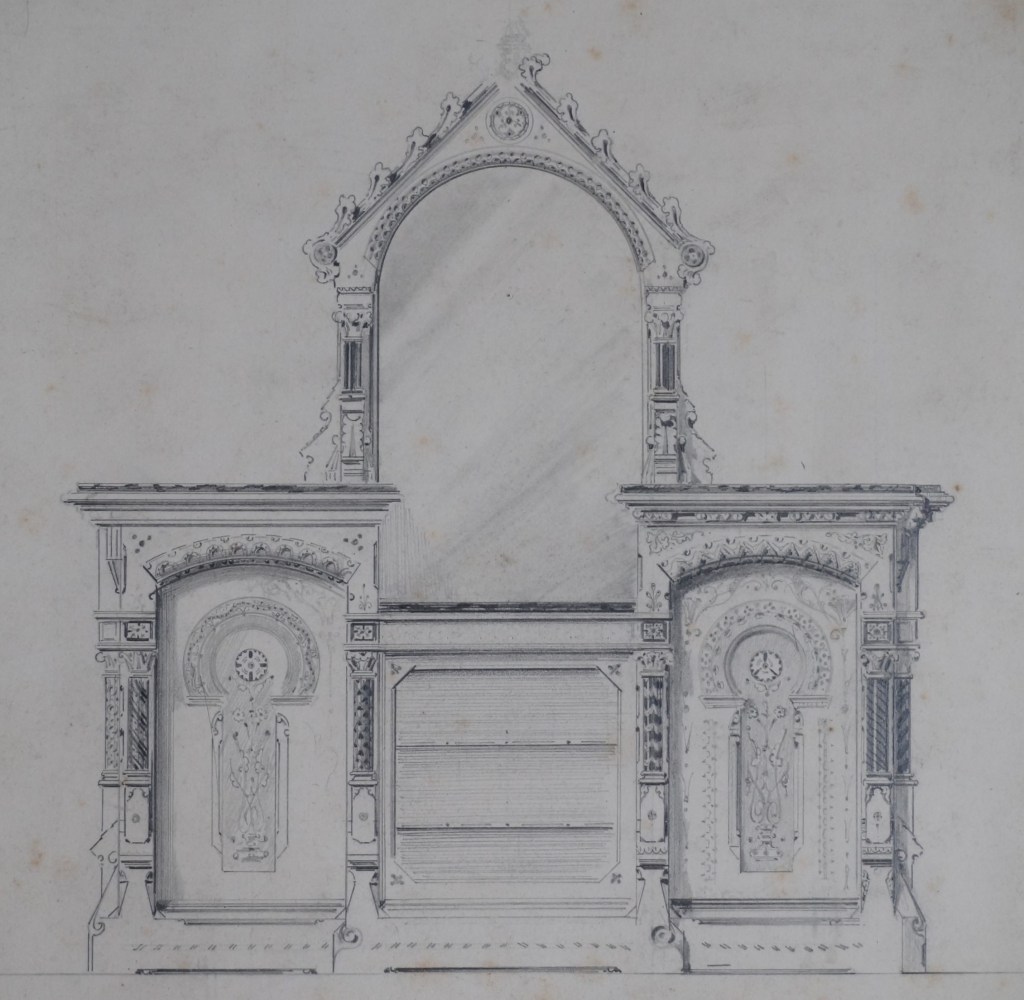

There are two elevation drawings – alternative offers for the same commission? – of a large, five-storey block that looks like it was intended for an inner-urban site engaged on both sides. There are no obvious clues to its function. Could it have been a department store? Or the headquarters for a large company? Something also needs to be said briefly about the drawings for furniture and various pieces of interior design – armchairs, tables, desks, fireplaces, cabinets and overmantels. Stylistically, they are varied, from overtly High Victorian to Louis-Quinze. The draughtsmanship is very different, they have been mounted in albums to make them easier to peruse, and they look less like the product of John Croft’s visionary imagination and more like that of someone with commercial nous – perhaps his architect son, Adolphus (1831-1893).

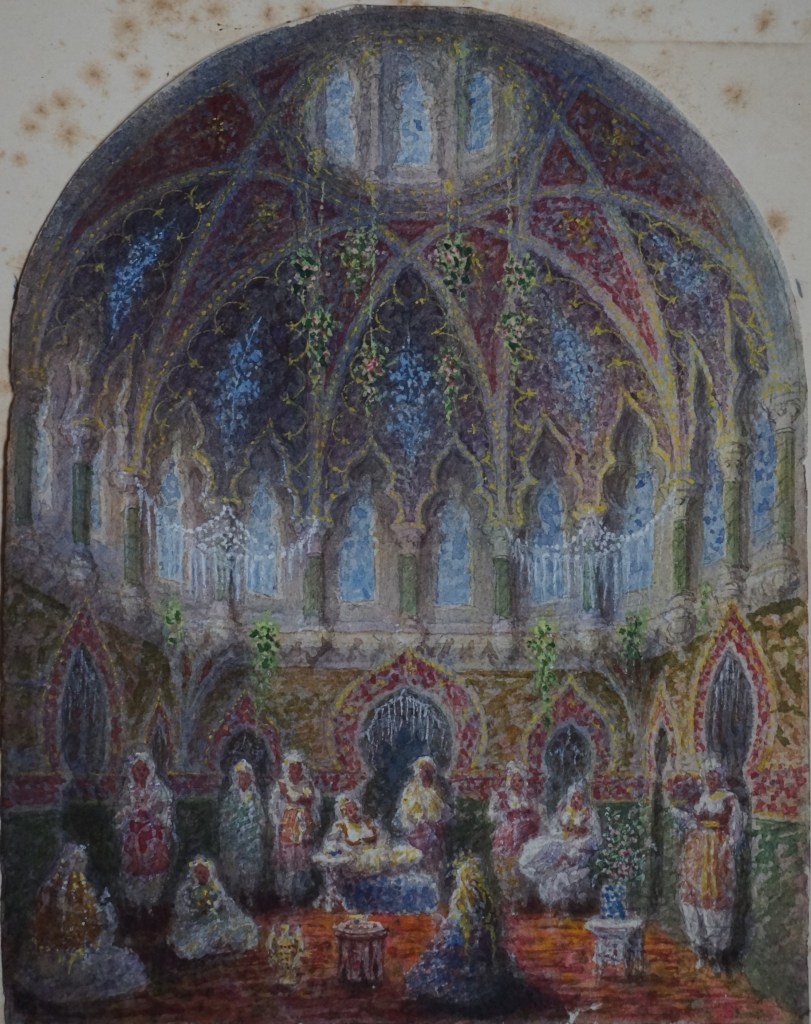

Capriccios

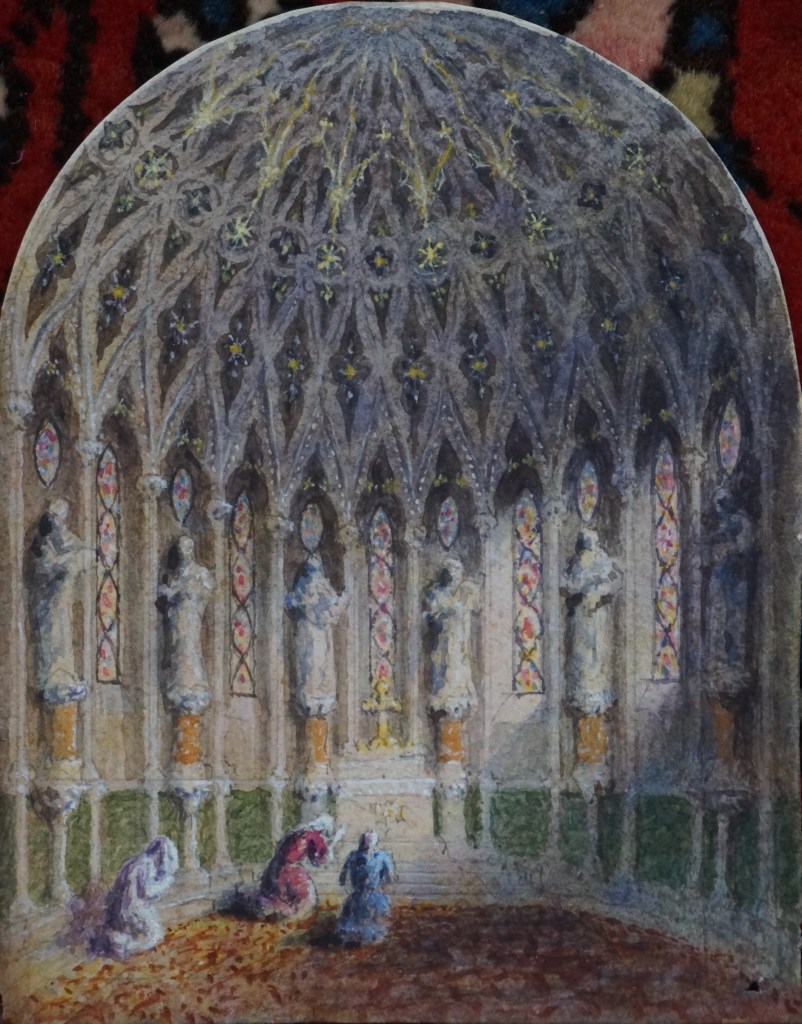

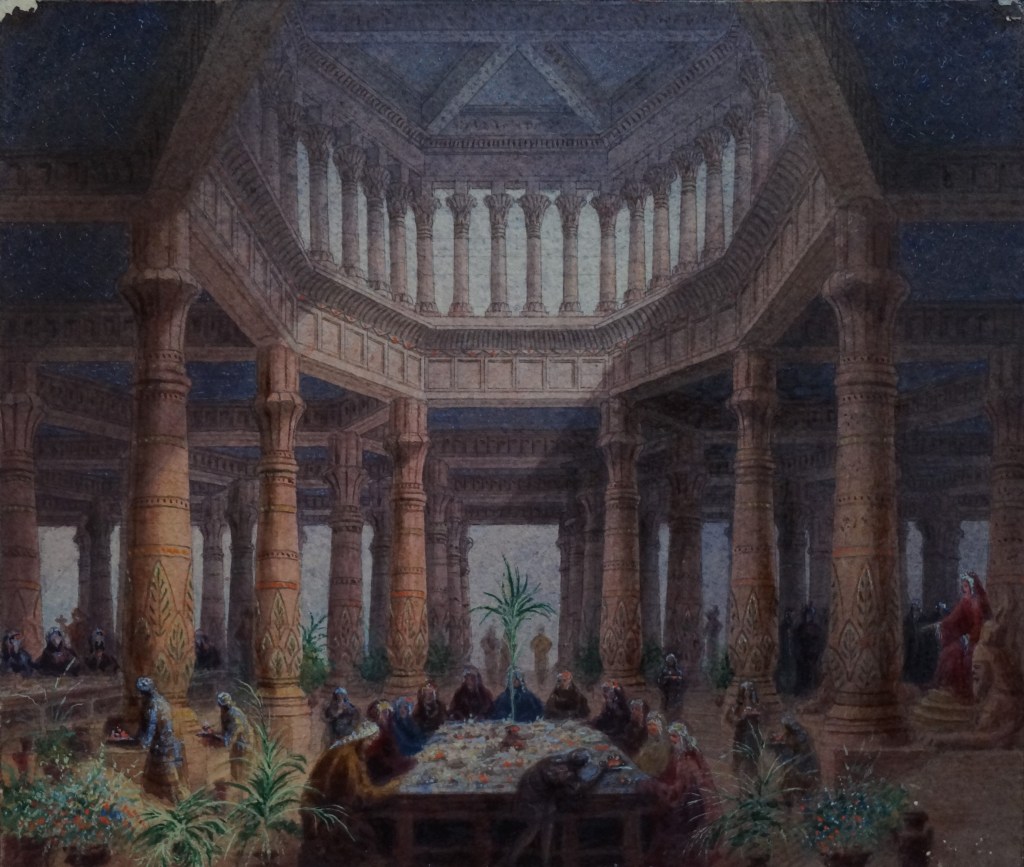

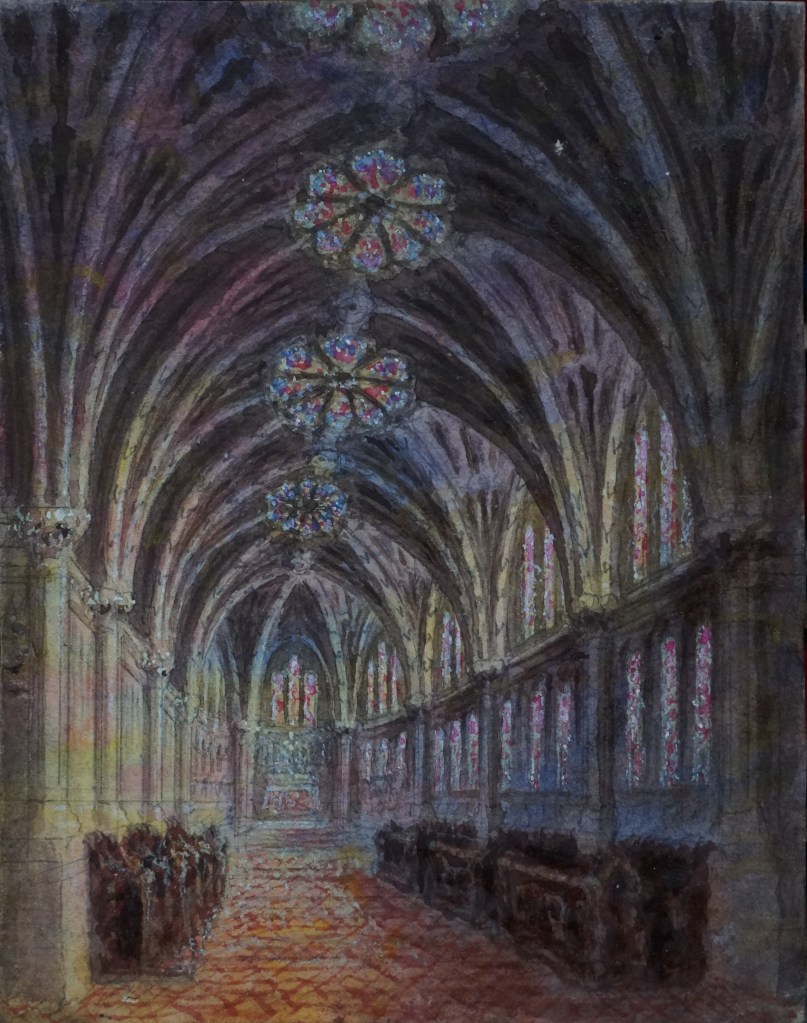

There can, however, be no doubt at all over the authorship of the gorgeous series of capriccios that form the highlight of the collection. They are almost exclusively interior views, none is large, yet they all glow with jewel-like colours and have been executed with real finesse. Everything suggests that Croft took particular delight in them and that they were produced for his own enjoyment. They can be divided broadly into three groups – Classical, Gothic and Orientalising. The classical scenes resemble nothing so much as elaborate stage sets and indeed are framed by what look like proscenium arches with curtains and valences. The Gothic scenes are pure expressionism, populated with people striking devotional attitudes, furnished with altars and benches and adorned with statuary. The treatment of the architectural forms is highly inventive to the point of foreshadowing 20th century stylisation of Gothic, incorporating original devices such as stained glass panels in a vault. No view can easily be conceived of as part of a larger whole, and again, they are quite theatrical in spirit. The orientalising capriccios could be subdivided into depictions of perhaps Moorish, perhaps Mughal scenes, and a chronologically even more distant past, which, given Croft’s interest in sacred art, one is tempted to interpret as backdrops to the Babylonian Exile or Slavery in Egypt.

Yet even if they were produced for his private amusement, these capriccios embody real architectural concerns. The preoccupation with large, central polygonal spaces has been mentioned above in relation to a design concept for a church interior; this emerges on repeated occasions in a group of orientalising fantasies depicting odalisques in spaces lit from above by a clerestory supported on an octagonal arcade. For all the exotic colour, the ultimate inspiration is from closer to home and must derive from the configuration of a Templars’ Church. The traceried windows of the interior reproduced at the top of this page look to have been cribbed from the Bishop’s Eye in the south transept at Lincoln Cathedral rather than anything east of the Mediterranean. The exaggerated cusping relates directly to Croft’s executed church designs, while the vault of an interior which rises to a central lantern looks to have been derived from the former monks’ kitchen at Durham Cathedral. The manner in which this is supported on intersecting ribs gives it a kinship with the second of the schemes for a church with a large domed space. Less easy to relate to any known examples in Croft’s output (although there are shades of the painter John Martin and architect Alexander Thomson) is a strikingly original interior where the same idea is resolved in trabeated forms supported on Egyptian-looking columns with lotus-leaf capitals. The surrounding spaces appear to be based on a repeated hexagonal module.

Conclusion

To reiterate one of my opening comments, what is reproduced here represents only a fraction of the material in the Croft papers. I have concentrated on original architectural designs, but the contents go far beyond these. The topographical views alone or else the capriccios would suffice for a lengthy blog post, and that is to say nothing of the large volume of papers including correspondence with clients, specifications, bills from suppliers (there is one dated 21st March 1864 from Clayton and Bell for the east window at Cold Hanworth), estimates from contractors and so on relating to executed works. It would be a rewarding but daunting task to examine these in detail and to correlate them with whatever turns out to have been deposited in public archives, as well as with detailed examination of what survives on the ground. Attempts to arrange access to the hall and church at Upper Shuckburgh have so far been fruitless. In the case of Birdingbury Hall and All Saints, Cold Hanworth – both private houses – they may prove impossible.

Though I believe that a scholarly account of Croft’s life and analysis of his work is essential for establishing his place in Victorian architecture, it is possible that it will not do much more than elaborate on the information already collated about his known output. There may be unidentified works by him still awaiting attribution, but my hunch is that these are unlikely to be anything substantial – perhaps the odd estate cottage, or minor alterations to a country house. It is unlikely that any textbooks on Victorian architecture will need to be rewritten. In my first post on Croft, I wondered whether there were lost masterpieces and unexecuted works (by which I meant things like competition entries or projects curtailed by circumstances) awaiting discovery. I now see that the answer to those questions has to be ‘no’: he entered the architectural profession relatively late and nothing about the papers suggests that he had a large practice or actively sought commissions. Perhaps, like Peacock – another architect with an intriguing but slender output – Croft’s main line of business was in fact surveying rather than designing; the Shuckburgh family’s landholdings might well have justified retaining him in such a capacity.

But whereas the details of Peacock’s life turned out to be scant and infuriatingly uninformative where influences on his professional formation and aesthetic preferences were concerned, as an artistic personality Croft is an entire world of his own. When I wrote the first blog post, I wondered whether the churches at Lower Shuckburgh and Cold Hanworth might be the only two highlights of an otherwise unremarkable career. Was there any information about Croft waiting to be discovered other than scant biographical data? Would he emerge from a study of it as a naïve artist whose success was more accident than design, or as a fully rounded designer? Even if it does not much expand the catalogue of known works, the family archive reveals Croft’s architectural imagination to have been richer and far more powerful that I could ever have anticipated. It must now be beyond any doubt that, whatever influence Sir George Shuckburgh might have exercised on the circumstances of the commission for the church at Lower Shuckburgh, the original character of the architecture sprang from Croft’s head alone. It is patently not the work of someone whose imagination was animated by someone better travelled and learned than he, and the purported influence of what Shuckburgh had seen in the Crimea must now be dismissed as spurious.

In his omnivorous delight in assimilating influences from the most diverse sources, of all the other architects featured on this blog, Croft most closely resembles Teulon, specifically the Teulon of St Mark’s, Silvertown with its fantastical Mudéjar overtones. But Teulon draws widely on outside influences to solve the practical and aesthetic problems with which he was confronted in his practice – to establish an archaeological precedent for a modern Protestant auditory church, to find a way of achieving maximum visual interest on a tight budget, to beautify Georgian fabric in a manner that works with rather than against the raw material, to broaden the expressive range of an historicising style and so on. In the case of Croft, these influences nourish a powerful, fertile but largely private imagination, which seems not to have depended on opportunities to embody itself in brick and stone to subsist and flourish. If, while working on the Warwick County Lunatic Asylum, he received any kind of training from Frederick John Francis, there is no sign of his having been influenced by that architect’s comparatively staid work. Lower Shuckburgh and Cold Hanworth are artist’s architecture, the fruit of a design process which proceeds from an overriding concern for picturesque, decorative and emotional effects. A desire for strongly individual expression takes precedence over established canons of taste. For all these reasons, Croft qualifies as a genuine architectural outsider.

As far as I know, no other architectural historian has ever looked at the Croft papers. Indeed, Laura Amalir told me that they had been viewed by several generations of the family as little more than a curio – had even been regarded with some embarrassment during the long period in the mid-20th century when High Victorian art and architecture were deeply unfashionable. It is a pleasure finally to be able to restore them to prominence and to share them with a wider audience.