It is inevitable that A.W.N. Pugin looms large in histories of Roman Catholic church-building in the 19th century. Yet in some ways he was as notable for the adopting the faith that he served through his architecture as he was for the buildings that he designed. Would Pugin be viewed in quite the same way by architectural historians had he been Anglican? He claimed not merely to be reviving the forms of the Middle Ages, but the entire theological, aesthetic, philosophical and ethical outlook that they implied.

Yet the Catholic church which Pugin burst in on when he converted in June 1835 was a very different institution to that which animated his vision. The Catholic Relief Act of 1791 restored the freedom of worship lost following the Reformation, but its spirit was to enjoin Catholics to keep a low profile, and this extended to the architectural treatment of places of worship, which were not to have a steeple or bells. Many of the churches built during this period closely resembled externally the contemporary chapels and meeting houses of Protestant nonconformist denominations. Stylistically, they were characterised by the plurality characteristic of the period. The growing influence of the fashion for Gothic was not ignored, but nor was it accorded hegemony. Major architectural statements were just as likely to be Greek Revival, Neo-Classical or Italianate. It was not full Catholic emancipation in 1829 which changed this; it was Pugin. But then there is no fervency quite like that of a neophyte.

Though the influence of Pugin would be felt until well into the 20th century, in some ways it did Catholicism a disservice. Its effect on the Church of England was so enormous that, architecturally speaking, the two denominations were left marching in uneasy lockstep. When, after what proved to be a false start, Catholics were ready to make major architectural statements in the capital, they did so in a manner that consciously avoided any invidious comparisons with Anglican church-building. Though they were diverse, none was Gothic. Herbert Gribble’s design of 1878 for the Brompton Oratory was an evocative recreation of an Italian early Baroque domed basilica, while J.F. Bentley’s Westminster Cathedral represented nothing less than an attempt to synthesise a contemporary architectural style from historicising sources. When stylistic plurality re-entered church-building in the late 19th century, Catholics embraced it as enthusiastically as any other denomination. Eventually they largely abandoned historicism when the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council accelerated their Church’s progress towards modernism.

In short, the history of Catholic church-building in Victorian Britain is about a great deal more than the rise and fall of Gothic. There is an important ‘other tradition’ – to borrow a phrase coined by Colin St John Wilson to describe the work of 20th century architects who refused to subscribe to a narrow, doctrinaire vision of modernism – and few buildings embody it quite so intriguingly as those which form the subject of this post. They constitute part of the remarkable record of church-building by the Weld family, which extends from the period just before the end of the penal times to the 1960s. It is, moreover, a history intimately bound up with people and place.

Chideock – the castle and the martyrs

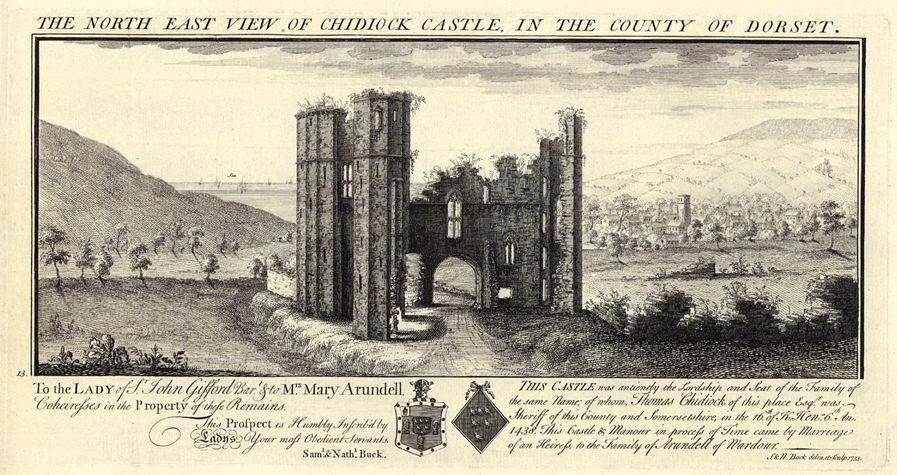

Chideock (pronounced ‘Chiddick’) is a village in southwest Dorset located just east of Bridport and about a mile inland from the coast. In the late 14th century John De Chideock, who at that point held the manor, fortified his dwelling and created what was apparently a substantial house. Around 100 years later, the property was acquired – apparently through marriage – by the Lanherne branch of the Arundells, a prominent Cornish gentry family. As devout Catholics, the Arundells found the Henrician Reformation unacceptable and maintained their adherence to what they saw as the only true faith. Their social standing and wealth initially offered some defence against official persecution, but in the circumstances confrontation was inevitable and things came to a head during the lifetime of Sir John Arundell (before 1527-1590). Despite benefiting from a number of emoluments, he refused to accept the Elizabethan settlement and actively supported the underground Catholic church. St Cuthbert Mayne, the first of the Catholic seminary priests – that is, clergy who had been trained on the Continent and were sent as missionaries to England – praised Sir John in his final address from the gallows when he was executed in 1577.

Around this time, Arundell seems to have put Chideock Castle at the disposal of seminary priests arriving at the nearby port of Lyme Regis, and it became an important local centre of Catholic worship and ministry. Such activity was brutally repressed and between 1587 and 1642 three seminary priests and four laymen – three of them members of the household and one a local resident who had converted to the faith – were arrested, imprisoned and then put to death at Dorchester. As the seat of a family that was not only recusant but also staunchly royalist in its sympathies, Chideock Castle was an obvious target during the Civil War and in 1645 Thomas Fairfax, the Parliamentary General, ordered it to be slighted. The destruction was not total, but it achieved the aim of flushing out the Catholic priests, who were forced to decamp to a nearby farmhouse known as Dame Hallett’s, where they turned the loft of the attached barn into a centre of clandestine worship.

The Welds and Chideock

The Weld family came originally from Cheshire and, like the Arundells, was recusant. In 1641, it acquired Lulworth Castle in east Dorset. This is a remarkable building put up during the first decade of the 17th century by Thomas Howard, 3rd Viscount Howard of Bindon, and is representative of a fashion for medievalising sham fortified castles which enjoyed some popularity during the reign of James I. Thomas Weld (1750-1810) was born at Lulworth and educated at the Jesuit-run college for English Catholics at Saint-Omer in the northern French province of Artois. This was a necessity at a time when English Catholics were effectively barred from studying at Oxford or Cambridge, which required adherence to the Thirty Nine Articles of Faith of the Church of England. During the course of Weld’s studies, the Jesuits were expelled from France and the college moved to Bruges in what was then the Spanish Netherlands. In 1775, Thomas succeeded his elder brother Edward (1741-1775) as heir to the family estates, which had been augmented since the purchase of Lulworth – in part through advantageous marriages and inheritances – and now numbered five, including Stonyhurst and Shireburn in Lancashire.

Five years later, Thomas Weld embarked on a major building campaign at his seat when he commissioned John Tasker (c. 1738-1816) to remodel the interior of Lulworth Castle. The work was completed in 1782, but does not survive, having been destroyed when the Castle was gutted by fire in 1929. Tasker was a practising Catholic, who worked mainly for clients drawn from the recusant gentry and aristocracy, such as Weld. He also founded a dynasty of architects who found much work during the great building campaigns that followed Emancipation, notably his grandson, Francis William Tasker (1848-1904). Weld then commissioned Tasker to design a Catholic chapel, construction of which commenced in 1786 on a site in the grounds and was completed the following year. This was to be the first new Catholic place of worship (not counting private house chapels) to be built in England since the Reformation – a bold, potentially even a risky move. Though the penal laws were no longer as brutally enforced as had been the case in the preceding two centuries, anti-Catholic sentiment had been strong enough to bring about the Gordon Riots six years earlier. A provision in the Papists Act of 1778 which allowed Catholics to join the army (though it did not grant freedom of worship) was used to whip up paranoia about fifth columnists acting in the interests of the Catholic powers at that point hostile to Great Britain. Over the course of several days in June 1780, Catholic places of worship in London, as well as a number of public buildings, were looted and burned, and troops eventually had to be deployed to restore order.

But Weld had friends in high places. He was on close terms with George III, whom he subsequently entertained at Lulworth Castle on several occasions, and also much involved in campaigning for the relief of the penal laws. A family tradition has it that the king did not explicitly grant permission for a functioning church; he instead assented to the construction of a mausoleum and went on to state that how it was arranged internally was Weld’s own business. Whether this can be historically substantiated is unknown, but, in common with most churches erected between the Relief Act of 1791 and full emancipation in 1829, externally Tasker’s design lacked any unequivocally ecclesiastical trappings, such as a bell tower and statuary, or indeed any ornament based on religious symbolism. The airy, spacious, domed interior – an essay in the cool neo-classical manner of James Wyatt’s school – is another matter.

Weld had 14 children, the eldest of whom, Thomas Weld (1773-1837), took holy orders in 1820 following the early death of his wife and was eventually made a cardinal in 1830 by Pope Pius VIII while visiting Rome, where he then settled. As such, he became the first Englishman to bear that title since Philip Howard (1629-1694). In 1802, Thomas Weld senior purchased the Chideock estate for his sixth son, Humphrey. It lacked a suitable residence and in c. 1810 Humphrey Weld had built on the site of Dame Hallett’s farmhouse a substantial house, which is known as Chideock Manor. Tasker was approached for a design, which survives in the Weld papers in the Dorset Record Office, but for reasons that are currently unknown it was never executed. The interior incorporates spolia presumably salvaged from the ruins of the castle, such as fireplace lintels and chimneypieces, and the Manor was linked to the barn which had been used for clandestine worship during the penal years. This was turned into a proper chapel and fabric possibly dating from this period suggests that Humphrey Weld may have furnished and decorated the interior with some splendour. Archive photographs show that none of this showed externally and indeed the building presented a blind elevation to the road outside.

Charles Weld and what he built at Chideock: the mortuary chapel

Humphrey Weld died in 1852 and his estate was inherited by his son, Charles (1812-1885), who continued the family’s architectural exploits. One surmises that his father’s death prompted Charles to address the fact that, though the family was now well established at Chideock, it had no dedicated place of burial. A Catholic cemetery was laid out on a site slightly to the north of the Anglican parish church of St Giles in the centre of the village and work then began on a mortuary chapel, with Charles acting as his own architect. It is remarkable not only as an excellently preserved example of a rare building type, but also as a most original and strikingly forward-looking piece of architecture, to which one could be forgiven for ascribing a date a good half a century later.

Externally it is a compactly modelled form based on the ground plan of a Greek cross. The proportions and steep pitches of the roofs evoke the architecture of the Middle Ages. Some of the detailing is overtly Gothic, such as the clasping buttresses and a shouldered, Caernavon-type doorway, while the bands of fish-scale slates provide a distinctly High Victorian touch. Yet these devices are applied too sparingly to add up to a finite statement of the style. ‘Y’-tracery is curiously jammed into small oeil de boeuf windows. The rubble coursing of local stone is relieved not by architectural devices, but by two crosses, enormous in relation to the proportions of the elevations that they adorn. That to the east is entirely of abstract forms, executed of red bricks with a border of over-fired bricks, the only portion of dressed stonework being a diamond-shaped relief at the intersection of the arms bearing a complex monogram made up of the Chi-Rho, Alpha and Omega and the IHS Christogram.

That to the west is no less striking – the crucified Christ depicted in shallow relief, the upper section inscribed within an octagon with the symbols of the Evangelists in the angles of the arms of the Cross and, above Pilate’s inscription, the Mystic Lamb flanked by doves. It has all the monumentality of a free-standing Crucifix – and, indeed, a stepped plinth at the base – but has been drawn into the wall plane. The effect, like that of everything else about the exterior, is primitive, but a knowing, studied kind of primitivism, deliberately rough hewn. Nothing like it is encountered again in English architecture until the landmarks of the Arts and Crafts movement at the turn of the 20th century, and the Weld chapel makes an instructive comparison with W.R. Lethaby’s church of All Saints, Brockhampton in Herefordshire of 1901-1902.

Given the diminutive proportions of this structure, opportunities for innovative spatial organisation within inevitably were limited. Four pointed arches define a crossing, there are stepped brick cornices and the interior is open to the panelled underside of the roof structure. But this is more than made up for by the lively, exuberant decorative scheme. The walls are clad up to dado height in tiling with bold geometrical patterns, boldly coloured. Running along the top is a terracotta frieze with a repeated Chi-Rho encompassed by a laurel wreath and various other Christological symbols. Some of the gables, the wall above the crossing arches and all the ceilings are divided up into repeated patterns resembling coffering. These frame a wide variety of scenes, depicting persons and events from Scripture, as well as allegories and symbols, some in colour and others in grisaille. There are inscriptions in scrolls and bands of lettering. Smaller spaces are filled with medallions and there is a row of roundels with portraits of mainly Post-Reformation saints, including English martyrs such as St Cuthbert Mayne and Fr Hugh Green of Chideock (put to death in 1642, although not beatified until 1929). What is most striking after the exterior is that the aesthetic is determinedly neo-Classical.

Charles Weld and what he built at Chideock: Our Lady, Queen of Martyrs and St Ignatius Loyola

Whether the need arose from a burgeoning congregation or whether the primary motivation was simply a desire for greater visibility is for the present unknown, but in 1870 Weld began work on a major enlargement of the old barn chapel attached to Chideock Manor. A nave was thrown out to the west, aligned on an axis at a right angle to it, thereby producing a building with a ‘T’-shaped plan. This allowed the church to be oriented and, although most of the exterior could only be properly appreciated from the pleasure grounds and thickly wooded park, still gave it much greater presence than before in the ensemble of the manor and outbuildings, especially when they were viewed from the public domain of the road outside.

The entrance front is arresting. The porch takes the form of a lean-to narthex with a chunkily proportioned, partly blind arcade supported on dwarf columns. Above, filling the upper part of the wall and gable is a device which has the visual presence of a rose window, yet admits no light to the interior (in any case, the space immediately behind it is an organ loft). In the centre is a statue of the Virgin Mary carved in the round, contained within a deep circular recess with a majolica backdrop of a vesica and stars. Circling it are eight majolica roundels containing depictions of the Seven Sorrows of Mary with, in the uppermost, the Crown of Thorns and her heart pierced by seven swords. All these are brightly coloured; the interstices, also of majolica, are monochrome and depict in relief crossed lilies and martyrs’ palms. Though the historical precedents are to be found in the early Italian Renaissance, the incorporation of a work of applied art as the centrepiece of an architectural scheme where ornament is applied very sparingly again looks forward to the Arts and Crafts movement.

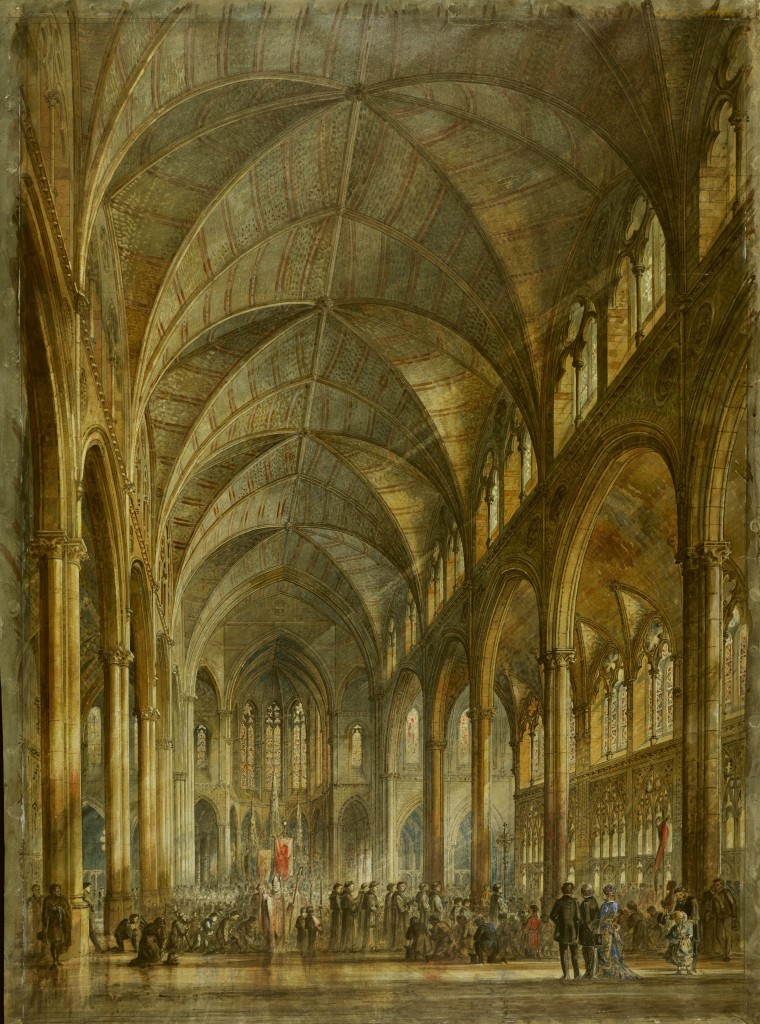

In form, the nave is based on an early Christian basilica, although the guiding concern seems to have been to evoke the image of the prototype rather than an archaeologically correct recreation. Within, round-arched arcades of four bays are supported on single columns. It is a grand conception that in photographs belies the actually modest proportions of the building, which can be properly appreciated only in person. Indeed, given the rich decorative scheme in a variety of media, which is maintained throughout, and the limited amount of light reaching the interior, the overall effect is almost claustrophobic. Much of the decorative scheme was executed by Charles Weld himself. He carved the capitals of the nave arcade, which combine vigorous stiff leaves with a variety of symbolic motifs. One supposes that he was also responsible for the capitals to the colonettes supporting the triplets of clerestory windows in each bay. In this he was assisted by Benjamin Grassby (c. 1837-1896), an apprentice of George Myers, who had worked for Sir George Gilbert Scott and Thomas Earp between c. 1856 and 1860 before settling in Dorchester and setting up a highly successful sculpture and stone carving business.

Weld was responsible for much of the wall decorations in the aisles, which are monochrome and based on the Instruments of the Passion to complement the framed paintings of the Stations of the Cross. He also designed the altars that terminate the aisles to the east. That on the north side is dedicated to the Sacred Heart and is housed in the central niche of a shallow polygonal apse with an elaborate painted scheme. That to the south, dedicated to St Ignatius Loyola, is set in an arched recess and richly carved and gilt, with a central statue of the saint encircled by portraits in medallions. Both altars have stone frontals richly carved in shallow relief.

A frieze between the arcade and clerestory contains portraits of 34 English martyrs and Sir John Arundell, all painted by members of the Weld family. The Chideock martyrs are nearest the sanctuary. Other martyrs represented include St Thomas More, St John Fisher, St Cuthbert Mayne and Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury. The interior is open to the structure of the arch-braced roof, but this is finished with boarding to allow for an extensive decorative scheme, also executed by Weld. The surface is divided into squares filled with two-dimensional patterns based on classical motifs with medallions in the centre bearing various symbolic motifs. The scheme become increasingly elaborate towards the east end, with figures depicted in grisaille bearing martyrs’ palms, portraits of the Evangelists and so on. Stylistically, it is consistent with the ceiling decoration of the Mortuary Chapel, though the colour scheme is muted by comparison – at any rate, inasmuch as could be judged in the rather dim lighting.

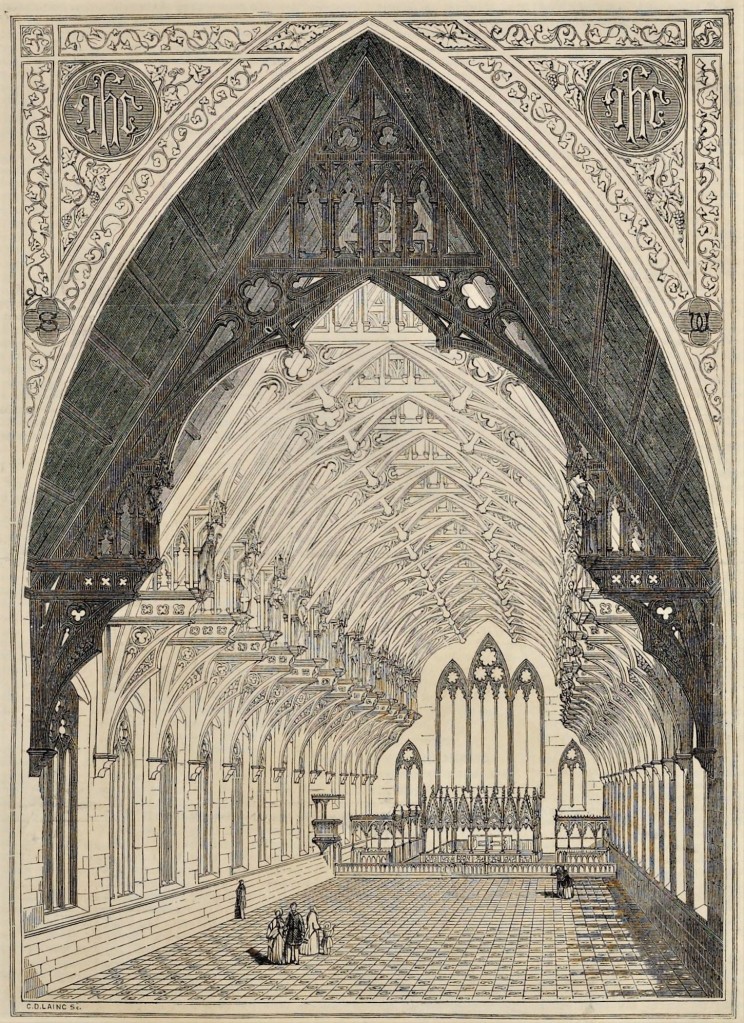

The church was consecrated in 1874. No illustrations or plans have yet been discovered which show how the east end was arranged, but it is not difficult to imagine that the fabric of the old barn chapel must have compared increasingly unfavourably to Weld’s splendid nave. As the liturgical focus of the building, the altar demanded a more dignified setting. Around ten years later, it got it when the east end was remodelled. Though Weld was still alive, on this occasion a professional architect was engaged. The reasons for that await discovery, but the chosen solution displays a certain structural daring and, conceivably, Weld feared that his own lack of technical expertise might lead to problems. The shell of the barn chapel was retained, but a new domed structure was dropped into it, forming a sort of gigantic baldacchino. It is supported on all four sides by serlianas, though the central arch of each one is pointed rather than round. Pointed too are the squinch arches in the angles, which effect the transition from square to octagon. Above, more arches with pendentives transform the octagon to a circle, on which rests a spherical dome, lit by sexfoils at the angles. The decorative treatment of this part of the building is very different to the nave. Instead of stiff leaf carving, the capitals, which are supported on octagonal shafts, are modelled with flat surfaces and deeply incised ornament based on abstracted motifs. The entablature is inscribed with the opening verse of the Canticle of David (1 Chronicles 29:10) ‘Benedictus es, Domine Deus patrum nostrorum, et laudabilis in saecula’. Given the historical context of the church, the phrase ‘Deus patrum nostrorum’ – literally ‘the God of our fathers’ – carries particular weight.

The serliana at the junction of the nave and sanctuary effectively functions as a chancel screen, while that on the east side is used to create a setting for the reredos. The east wall of the old barn chapel was built up externally with a transverse gable and decorated internally with an elaborate and vibrantly coloured and patterned painted scheme. In the centre is a vesica with a gilt statue in the centre, supported on a bracket, of Our Lady being carried heavenward by angels. This is lit with baroque theatricality by daylight from a concealed source – a cinquefoil in the transverse gable. The combined free-standing altar and reredos is richly carved and polychromed, with paintings executed by members of the Weld family of their patron saints: St Edmund, St Lucy, St Humphrey and St Apollonia. But the Gothic detailing is weak, generic and at odds with its architectural setting. It does not appear to have been designed for this location and probably predates it. On the north side of the sanctuary is the family pew, to which there was formerly direct access from the manor house (since it was sold in 1996 no longer inhabited by the Weld family), while to the south is a largely blank wall, with a doorway giving access to the sacristy. This contains a now badly faded but once elaborate painted scheme, perhaps dating from Humphrey Weld’s remodelling of the barn chapel in 1815.

Internally, the dome is painted light blue and powdered with gilt stars, as shown in the photograph forming the featured image at the top of the page. There is a gilt roundel in the centre consisting of densely packed bands of ornament with the Hand of God in the middle flanked by the Alpha and Omega. But externally is it finished with diagonal bands of coloured and glazed tiles, rising up to a lead-clad finial and gilt cross. This can be glimpsed in views from the west, in which it picks up the majolica reliefs of the entrance front, but can only be properly appreciated from the grounds of the manor. The tiles were reinstated in 2014, when a slate covered mansard roof, which had been substituted for them in the 20th century, was removed.

Weld’s collaborator

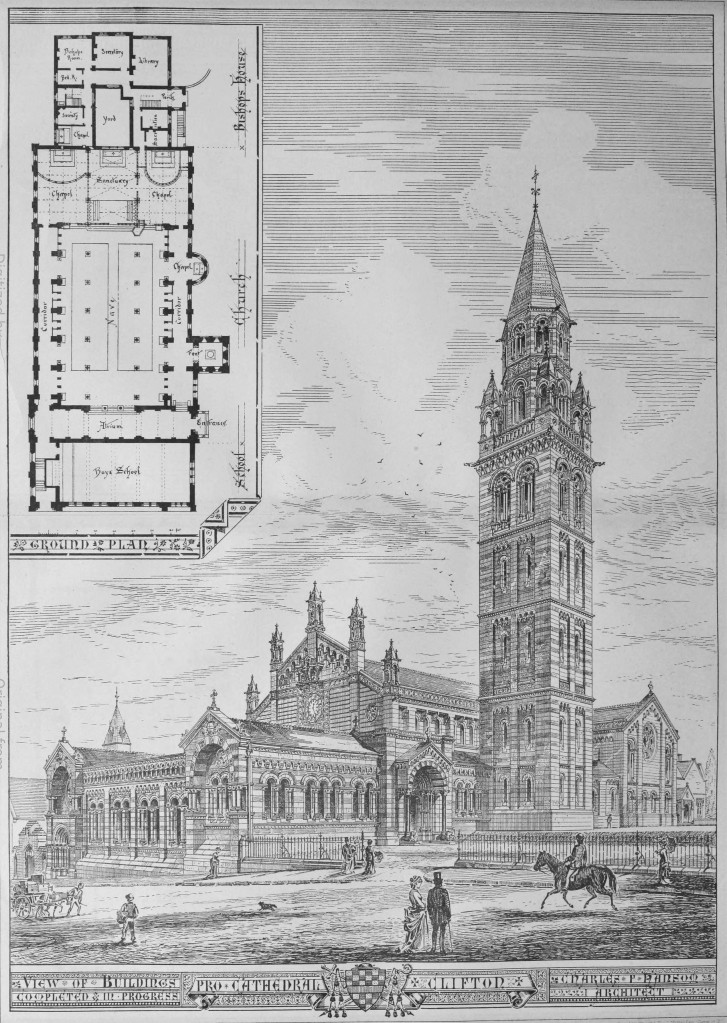

The nominal architect of the domed sanctuary was Joseph Stanislaus Hansom (1845-1931). He was born into a dynasty of Catholic architects, who had attained their standing thanks to the post-Emancipation building boom. Joseph’s father was Joseph Aloysius Hansom (1803-1882), a native of York who descended from a line of recusants. During his early career in the 1820s-1840s, he secured a number of prestigious commissions, such as Birmingham Town Hall, won in a competition of 1831, which he entered jointly with Edward Welch (1806-1868). The two young architects stood surety for the builders and, as a result of underestimating the cost of transporting the hard stone from Anglesey with which the building was to be faced, went bankrupt in 1834. Hansom then left architectural practice for several years and went into business, taking out a patent in 1834 for what came to be known as the Hansom cab and then in 1842 setting up The Builder, the first issue of which appeared in December that same year. He then returned to architectural practice, now thoroughly imbued with the teachings of Pugin, as an ecclesiastical specialist. He produced some of the most boldly original designs of the 1850s and 1860s, such as St Walburge’s in Preston (1850-1854), where a mighty single vessel, to which a crazily tall tower and spire were added in 1869, is spanned by an immense hammerbeam roof. At St Wilfrid’s in Ripon (1860-1862), the building culminates in an extraordinary lofty apsidal chancel that is taller than the nave and treated as a tower-like form, a device tried again at St Mary’s, Lochee in Dundee of 1865. At the Jesuit church of Holy Name, Oxford Road in Manchester, inventive planning based on medieval Spanish prototypes and structural innovation – the use of terracotta blocks allowed the span of the vaults to be greatly increased – led to the creation of an exhilaratingly broad and lofty interior.

Hansom taught his younger brother, Charles Francis Hansom (1817-1888), who went on to design a number of equally powerful buildings, notably St John the Evangelist in Bath (1861-1863), whose 220-foot-tall spire is one of that city’s landmarks. Charles Francis Hansom’s son, Edward Joseph Hansom (1842-1900), after training with and working in partnership with his father, moved to Newcastle in 1871 and formed a new partnership with Archibald Matthias Dunn (1832-1917). Among other things, this practice designed the new chapel of 1882-1884 for Ushaw College in County Durham – the successor institution to the English College in Douai – and the cathedral-sized church of Our Lady and English Martyrs in Cambridge (1885-1890). Joseph Aloysius took Joseph Stanislaus into partnership in 1869 and the son was jointly responsible for some of his father’s works, including Holy Name in Manchester. The younger Joseph also took over the practice of John Crawley (1834-1881) on that architect’s death and oversaw the completion of a number of his commissions, such as the Cathedral of St John the Evangelist in Portsmouth.

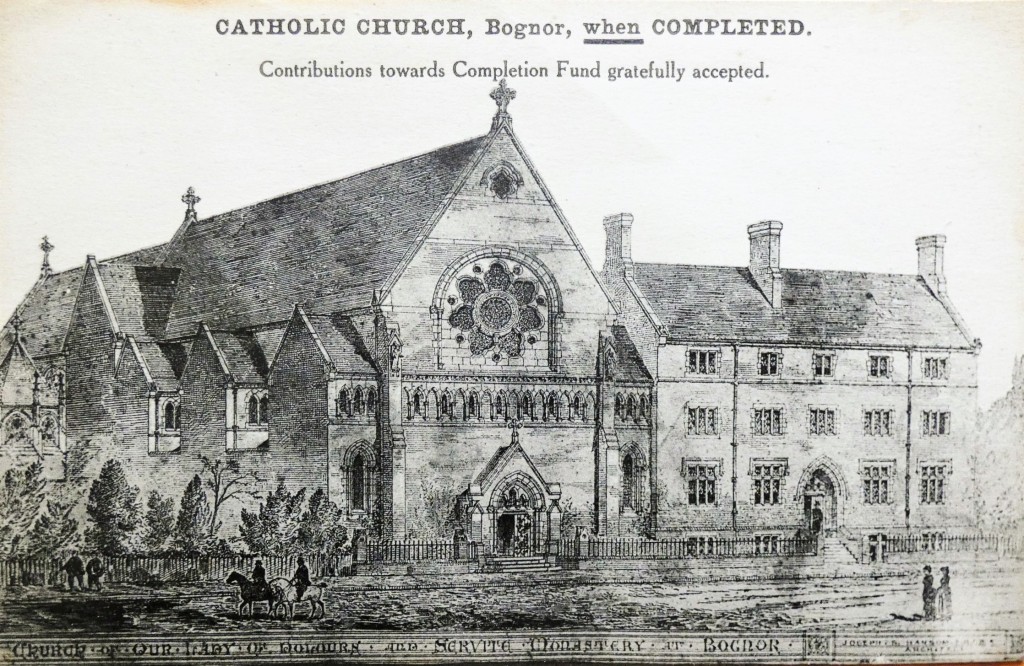

Yet his own architectural personality is hard to pin down. Though he could hardly have been better placed to acquire a comprehensive training and establish advantageous professional connections, in other respect his circumstances counted against him. There can have been little opportunity to emerge from the shadow of his father and uncle until both had retired, and by that point the opportunities for major new commissions were much decreased. Though more study is needed to give a proper account of his career, J.S. Hansom seems to have confined himself mostly to piecemeal additions to existing buildings, usually by this father. Only one complete design for a church by him has so far been traced – Our Lady of Sorrows in Bognor Regis, West Sussex, built in 1881-1882, although not executed in full. The facade is muscular Gothic, somewhat tardive for its date and handled without any great panache. The interior is relatively plain and, in any case, has been much altered in the 20th century. Yet there are works that hint at greater individuality, such as the original and powerfully modelled tower in a free Romanesque that he added in 1881-1882 to his father’s church of St Mary Immaculate in Falmouth, Cornwall.

The church at Chideock has been little altered since the completion of Hansom’s domed sanctuary and it avoided the kind of wholesale reordering carried out in so many Catholic churches following the Second Vatican Council. But the story of the Weld family’s architectural patronage does not end here, since in 1968 Sir Joseph Weld (1909-1992) commissioned what turned out to be one of the most striking and original post-war churches to be built for any denomination. The Church of St Joseph was built in 1969-1971 to serve the village of Wool north of Lulworth, the population of which had been swelled during the 20th century by the establishment nearby of military bases. Designed by Anthony Jaggard (1936-2020) of John Stark and Partners, it is a remarkable instance of a modernist architectural language at its most uncompromising being put at the service of the most traditional of briefs, as epitomised by the inclusion of a family pew – perhaps the last such to be built in any English church. Unusually for a Catholic church built in the years immediately after the Second Vatican Council, it eschews centralised planning for a conventional longitudinal configuration. The broad nave is spanned without any intermediate supports thanks to the use of a space-frame roof structure built of polished aluminium. Plans to install stained glass came to naught and, as Elain Harwood notes in England’s Post-war Listed Buildings, ‘the interior relies on the strength and quality of its materials’ for its architectural effect. The roof slopes gently upwards from west to east and the sanctuary – overlooked by the family pew on the north side – is top-lit by a lantern which externally forms the visual focus, making the building a distant echo of the Chideock church.

Conclusion

Assigning labels is a risky business. Though it is tempting to categorise Weld’s work as amateur architecture, the term cannot be fairly used without guarding against certain associations which do him an injustice. He was an amateur only in the sense that architecture was not for him a vocation. Though his aesthetic is highly personal, it is not naïve, nor is it wilfully eccentric – two qualities which sometimes arise from the lack of a professional grounding. As far as is known, Weld was his own paymaster and, within the limits of his own means, had total control over the execution of both buildings at Chideock. Neither the mortuary chapel nor the church is a fluke – they are both serious, carefully considered piece of architecture. But a great deal remains to be discovered about them and the influences Weld had absorbed, from which he subsequently distilled these designs. Reputedly, he travelled widely on the Continent and was prodigiously cultured, but for the moment these claims have to be taken on trust.

A brief examination of entries for Weld family papers in the Dorset Record Office returned by the on-line catalogue does not return any results that appear immediately relevant. Anecdotally, Charles Weld’s own papers were all lost in an accidental fire, which, if true, represents a huge loss to architectural scholarship. But some valuable conclusions can still be drawn from comparative study and, in turn, more questions invite themselves. The influence of the Gothic Revival was so pervasive by the time that Weld began work that to reject an architectural language based on the heritage of the English Middle Ages represents a conscious position. What, then, were his grounds for doing so? What was his attitude to Pugin and the other Goths? What was his measure of propriety for Catholic sacred architecture? Taking an early Christian basilica as a model for the nave at Chideock is unusual for the 1870s, considerably in advance of a trend in Catholic ecclesiastical architecture that, though extensive, only established itself much later – a locus classicus for it might be Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s church of St Alphege in Bath of 1925-1929. What prompted this choice? Joseph Stanislaus Hansom’s work at Chideock is very unlike anything of the school in which he had been formed and practised. Did Weld choose him from what was by that point a crowded field because of a sympathetic aesthetic outlook? Was Weld involved in the design process of the sanctuary and dome? If so, what were his and Hansom’s relative contributions?

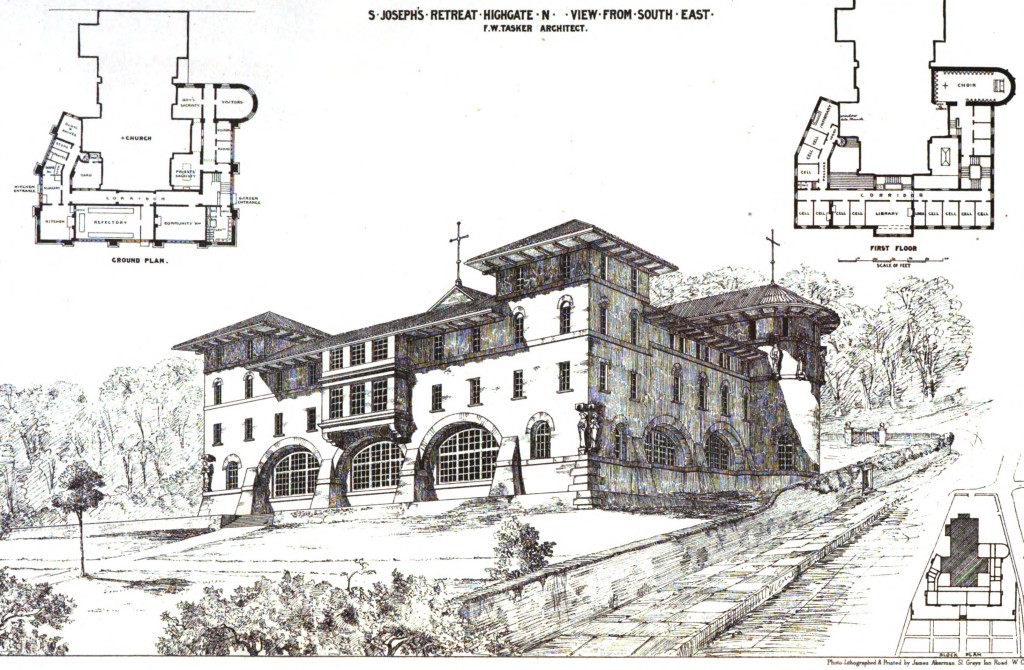

The way in which the mortuary chapel prefigures Lethaby’s innovations at Brockhampton has already been mentioned. But there are also some parallels from much closer in time. Taken as a whole, Our Lady, Queen of Martyrs and St Ignatius is reminiscent in its planning and, to a degree, also stylistically of St Joseph’s Church in Highgate, London, built in 1888-1889 to the design of Albert Vicars (1840-1896). That building also incorporates a broad nave based loosely on early Christian prototypes. Here, too, the it leads towards a domed space, which, instead of rising above a crossing, encompasses the sanctuary. Coincidence? Or is there a line of influence waiting to be discovered? It should be noted in passing that the community of the Passionist Fathers which serves the church resides in an attached clergy house of 1874-1875 by the same F.W. Tasker mentioned above as the grandson of the architect of the East Lulworth church. It exemplifies his spare, but refined classicising manner – every bit as radical a departure from the Puginian tradition as the other buildings discussed here.

The motif of the Serliana with a pointed arch to the central opening appears in a work by the remarkable French architect Pierre-Marie Bossan (1814-1888). A native of Lyon, he began his career with accomplished, but unadventurous work in an historicising vein, such as the church of Saint-Georges de Lyon in his home city, begun in 1842. During a prolonged sojourn in Italy begun in 1845, occasioned by the need to escape creditors after the failure of a gas-light company in which he and his brother had invested heavily, he visited Sicily. There, he discovered the highly individual buildings put up during the period of Norman rule on the island, such as the cathedrals of Monreale and Cefalù, and the Palatine chapel in Palermo, which combine Romanesque and early Gothic with Byzantine and Moorish influences. When Bossan resumed architectural practice on his return to France, his style had changed dramatically. The verbatim quotations from Sicilian prototypes are plain enough to see, but what is most striking is the way in which a wide range of diverse, even disparate influences have been synthesised into an idiom that is wholly personal and, crucially, immediately identifiable as a product of the 19th century.

Bossan’s most celebrated work is Notre-Dame de Fourvière in Lyons, a votive church begun in 1872 as a thank offering for the defeat of the Prussians at the second battle of Dijon two years earlier during the Franco-Prussian War. It his wholly characteristic of his mature style, but the building where a kinship with Chideock becomes evident is the Basilica of St Philomena at Ars-sur-Formans in the Auvergne, built in 1862-1865 to house the shrine of Jean-Marie Vianney (1786-1859), the parish priest under whole influence Bossan became a devout Catholic, who became the subject of a cult soon after his death and was eventually canonised in 1925. Bossan produced a church on a centralised plan based on an irregular octagon with a central lantern. It is in the vestibule-like space forming the junction between this and the medieval nave, retained in commemoration of Vianney, that the Gothic serliana appears.

Architectural scholarship is a good deal more than an ‘I-Spy’ game of identifying shared devices, of course, and one would not want to push the comparison. Perhaps Weld was aware of Bossan’s work and drew inspiration from it. But perhaps the points of similarity are entirely coincidental and arose quite independently of each other. What does, however, seem plausible to me is that both architects shared one of the great preoccupations of the 19th century – the search for an authentically contemporary idiom. Though in Britain the Gothic Revival produced many works of great power and originality, in the ecclesiastical field there is all too often a sense that the architects (and certainly the clergy) of the Middle Ages are looking over the designers’ shoulders. The sources may be diverse, but there is always a great concern with archaeological precedent. This perceived failure of Victorian architects to produce a style that belonged wholly to their own century weighed heavily on the minds of certain representatives of the profession. ‘How is it that there is no modern style of architecture?’ was the title of an after-dinner address given by no less a figure than Alexander Thomson (1817-1875) in April 1871 to the Glasgow Institute of Architects. In it, he appealed for an understanding of the fundamental laws that had guided architecture of all civilisations and periods to replace canons of taste based on archaeological fidelity, which he hoped would free the art from ‘the bondage of dead forms’. But while all that is clear enough where Thomson’s inimitable architecture is concerned (and it is sometimes forgotten that he was classed by Goodhart-Rendel as a ‘rogue’), it can only be advanced as a tentative hypothesis in relation to the church and mortuary chapel at Chideock.

To return to the opening of this conclusion, the kind of terms usually applied to buildings such as these – to ‘amateur architecture’ one might add ‘eclectic’ – are loose-fitting and unhelpful. If there is no pat label to hand, then they are categorised apophatically in terms of what they are not, which of course in this instance means Gothic. A short study like this can do no more than highlight possible lines of inquiry: there must be a Master’s dissertation at the very least and, quite possibly, a doctoral thesis in Weld’s work at Chideock, and it is unlikely that we could arrive at a proper understanding of it without viewing it in a very broad context. But whatever such a study brings to light, this is architecture that deserves at last to be understood on its own terms.