The 19th century was the age of Romanticism. Though its influence was felt in all the arts, many of the impulses driving the Romantic movement were literary in origin and one of their purest expressions is in the archetype of the Romantic hero – fated to be an outcast from society by incomprehension of his brilliance, doomed to tragedy by excessive sensitivity to the brickbats that his daring and originality elicit. Many creative figures of the period embodied these tropes to some degree, both consciously and unconsciously, but in English architecture few, perhaps, to quite the same extent as Enoch Bassett Keeling (1837-1886).

Unlike some of the architects featured on this blog, Keeling has had the good fortune to have been the subject of academic study. A full account of his life and career is given by James Stevens Curl, whose interest in the architect goes back to the 1970s, in ‘Acrobatic Gothic, freely treated: the rise and fall of Bassett Keeling (1837-86)’, from which most of the information here is drawn. This essay appears in a collection edited by Christopher Webster published under the title of The Practice of Architecture (Reading: Spire Books, 2012) and, since that is still available, I will do no more than outline here Keeling’s professional and personal biography.

Keeling was born in Sunderland to the then-minister of the Sans Street Methodist Chapel. Keeling senior led a peripatetic life, which may explain why his son received his architectural training in Leeds. Here, he was articled for five years at the age of 15 to one Christopher Leefe Dresser (c.1808-after 1891), during which period he attended the Leeds School of Practical Art, where he was awarded a medal for drawing in 1856. By December 1857 he had moved to London and set up his own practice. He seems to have disliked his first name and from early on either styled himself E. Bassett Keeling or dropped it altogether to use his middle name instead – Bassett Keeling was not a double-barrelled surname. In January 1860, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects and in March he married nineteen-year-old Mary Newby Harrison.

Evidently ambitious and dynamic, he quickly came to notice as an architect of ecclesiastical buildings and, still not even 30, won a crop of commissions for new Anglican churches and Nonconformist chapels, mostly in London and the surrounding area. Between 1864 and 1866, Keeling was in partnership with one John Richard Tyrie (1838-?), although the nature of their collaboration is not clear. A brief catalogue – by no means exhaustive – of works from that period is given here:

- St Mark’s, St Mark’s Road, Notting Hill, London (1862-1863)

- St Paul’s, Maryland Road, Stratford, London (1862-1864)

- Wesleyan Chapel, Waterloo Road, Epsom, Surrey (1863)

- St George’s, Campden Hill, Kensington (1864)

- St Paul’s, Anerly Road, Upper Norwood (1864-1866)

- Wesleyan Chapel, Mayfield Terrace, Dalston, London (1864)

- St Paul’s, Greenhill, Harrow, Middlesex (1864)

- St Andrew’s, Glengall Road, Peckham, London (1864-1865)

- Christ Church, Old Kent Road, Camberwell, London (1867-1868)

- St Andrew and St Philip, Golbourne Gardens, Kensal New Town, London (1869-1870)

- St John the Evangelist, Killingworth, Northumberland (now North Tyneside) (c. 1869)

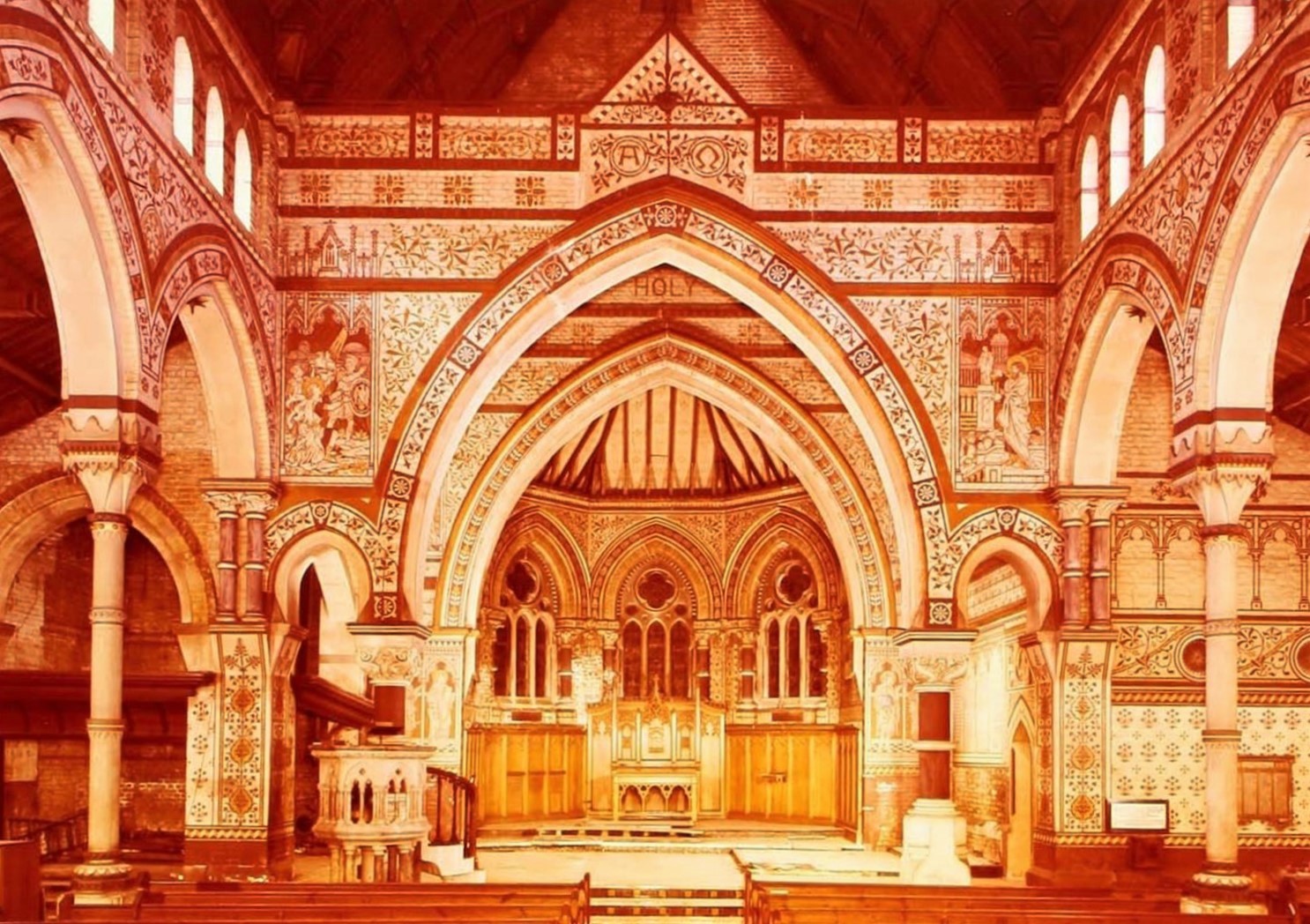

Keeling’s success seems to have been due mainly to good business practices and diligence. His churches were economical, providing large numbers of sittings for a very competitive price per capita. He kept within budget and his buildings were delivered swiftly and on time. Stylistically, they are immediately identifiable as High Victorian – strident, colourful, vigorous and uncompromising. It is young man’s architecture, boisterous and self-confident. Indeed, it is almost a cartoonish parody of Victorian architecture à la Osbert Lancaster. Keeling’s distortions, sometimes verging on the grotesque, of stock devices of the period – plate tracery, constructional polychromy, restlessly varied wall surfaces, spiky ironwork, chunky and chamfered timberwork, vigorously moulded cast iron columns – take to extremes an already bold aesthetic. Even some of his contemporaries found his work indigestible, dismissing it in terms that prefigure the mid-20th century rejection of High Victorianism as wilful ugliness and a lapse of all the canons of good taste.

H.S. Goodhart-Rendel therefore had good reasons to identify Keeling as a worthy for inclusion in his 1949 lecture, ‘Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era’, dedicated to figures with a strongly personal idiom who, he believed, had no counterparts among their peers or followers among later generations. The scope of lecture was broad, but the term ‘rogue architect’ has subsequently come to be used in a much narrower sense to denote practitioners active in the 1850s-1870s who propounded the most idiosyncratic and wilful brands of revived Gothic. Goodhart Rendel identified their work in the ecclesiastical sphere explicitly with ‘low’ Anglican churchmanship. Subsequent commentators have found cause to question this generalisation, yet for all that the modern understanding of the term in the context of High Victorian architecture is founded primarily on the reputation of figures such as Keeling. ‘Rogue’ implies moral censure, not just a maverick nature, and it seems to have been the lack of high seriousness that elicited it. Boldness was permissible, but not whimsy for its own sake: ‘When [William] Butterfield hit what he regarded as a frivolous and self-indulgent age full between the eyes’, said Goodhart-Rendel, ‘he did it of high purpose’. By contrast, he struggled to find any guiding aesthetic principle in Keeling’s churches beyond an intent to ‘try very hard to be amusing’.

He deemed the idioms of Keeling and others of his ilk, such as Robert Louis Roumieu and Joseph Peacock, far too disparate to qualify as a school: ‘the general resemblance of their attempts was due not to the similarity of their efforts but to the identity of the victim’. But he does draw an intriguing parallel with broader tastes of the 1860s – ‘Those were the days, in costume, of the longest whiskers, the most spacious crinolines, and the biggest stripes and checks’ – and one whose veracity it would be interesting to see tested by fashion historians.

Though remembered chiefly as an architect of churches, Keeling also handled secular commissions. But though these gave rise to no less engaging flights of architectural fancy, this side of his practice was commercially much less successful and, indeed, seems to have precipitated his downfall. In 1863, he won a commission to remodel the Norfolk Hotel in Brighton as a combined hotel and gentlemen’s club and produced for it a wildly eclectic design with a vivid roofline and a striking cast-iron structure of balconies running the entire width of the main front. Alas, it had all the makings of a scam – apparently none of this was built and, following his dismissal from the project, Keeling had to pursue unpaid fees through the courts, eventually being awarded just £500 of the total of £1,300 due to him. Publicity gained, the scheme was eventually executed by another architect to a far cheaper design.

Around the same time, Keeling was engaged to produce a design for the Strand Music Hall and he rose to the occasion, producing what might well deserve to be reckoned his masterpiece. While the street front was every bit as commanding a presence in the streetscape as the Brighton Hotel would have been, the auditorium was sheer phantasmagoria. It amplified all that was most flamboyant and colourful in his architecture – literally so, since the ceiling incorporated stained glass panels and glass prisms, illuminated from behind by gas jets, and the capitals were made of beaten copper. With its galleries, it bore more than a passing resemblance to his ecclesiastical interiors, and this may have been why it was thought a bridge too far. While the churches never entirely wanted for admirers, the Hall was universally lambasted in the architectural press of the time and although Keeling tried, wittily and eloquently, to defend himself, this seems only to have poured oil on the fire.

Worse still, the Hall was a commercial failure, operating for just two years. When the venture collapsed, it took with it a considerable sum that Keeling himself had invested in it and on 25th January 1865 he was declared bankrupt. As can be seen from the dates in the list of churches above, he managed to continue in practice until the end of the decade, but then seems to have withdrawn from architecture for several years, and in 1872 he even resigned his membership of the RIBA. When he re-emerged at the end of the 1870s, he was concentrating on commercial and residential work and producing buildings of a very different kind. Though technically innovative – premises at 16 Tokenhouse Yard in the City of London incorporated an ingenious stepped iron and glass structure at the rear to maximise the amount of light and air reaching the interior – they show no trace of the idiosyncrasies of the previous decade.

The revival in Keeling’s fortunes did not last long. In December 1882, his wife died while giving birth to their fourth son, who himself died just one year and five months later. Keeling had always been clubbable and gregarious, but grief evidently pushed him to indulge to an extreme degree and his death at the age of just 49 was the result of cirrhosis of the liver. He was buried with his wife and child at Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, but no memorial has been found and it seems that the plot was subsequently reused. His second son, Gilbert Thompson Keeling (1862-after 1894), tried to carry on his father’s practice, but after an ill-fated attempt to secure a commission for a National Concert Hall on Vauxhall Bridge Road gave up architecture and ended up earning his living in Ramsgate as a tram driver.

Personal tragedy was compounded by the ill fate of much of Keeling’s output. The Strand Music Hall was remodelled as the Gaiety Theatre, surviving only until 1903 when it was demolished for the construction of Aldwych. Bomb damage, post-war redundancy and a lack of recognition did for most of his ecclesiastical commissions. St George’s Campden Hill survives and is still a functioning Anglican church, but was badly mutilated by the removal of the galleries, then the spire and finally the apse. Much of the internal structural polychromy has been painted out. St Andrew’s, Glengall Road is structurally complete, but the fittings have largely been removed and the west gallery enlarged to form a mezzanine floor extending out into the nave. St John’s in Killingworth is also still a functioning Anglican place of worship and the least altered of the surviving churches, but the design is a good deal tamer than its counterparts in London (the interior is finished in plaster rather than polychromatic brickwork, for instance) and in any case lacks its intended south aisle and has no tower. In short, there is no place where one can today feel the full, unimpeded force of Keeling’s distinctive aesthetic.

Even more sadly, the only surviving records to give us any sense of what Keeling was really about are, unavoidably, either monochrome woodcuts in contemporary trade publications or else black and white photographs in archives. This badly sells short architecture that was intended to dazzle through its colour and vibrancy. But it is nonetheless possible to recover his intentions, thanks to the Dove Brothers, with whom Keeling worked on numerous occasions in the 1860s. This Islington-based firm of contractors amassed a remarkable collection of contract drawings by a wide range of architects during the course of its long existence, which was subsequently deposited in the RIBA Drawings Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum. By kind permission of that body, a selection is presented here.

5 thoughts on “Technicolour Roguery: the rise and fall of Bassett Keeling”