Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel (1887-1959) is someone who has loomed very large in this blog. I’m aware that I’ve quoted him extensively without fully explaining who he was and why he matters so much to any student of Victorian architecture. It is now time to bring him centre-stage, even if that means straying outside the chronological bounds of this blog. True, Goodhart-Rendel’s birthdate means that he formally qualifies as a Victorian. But he belonged to the same generation as Le Corbusier (also born in 1887), Mies van der Rohe (born 1886) and Walter Gropius (born 1883) – all figures who struck out against and sought to overturn a great deal of what the 19th century had stood for in architecture. The work from which I have quoted most extensively is Goodhart-Rendel’s lecture of 1947, Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era. It is relevant to three architects profiled in previous posts whom Goodhart-Rendel saw as taking the language of High Victorianism to highly idiosyncratic and ultimately inimitable extremes – E. Bassett Keeling, R.L. Roumieu and Joseph Peacock. The lecture yielded a term which has proved to be a very convenient shorthand for the wildest emanations of the 1860s – ‘Rogue Gothic’.

A celebrated scholar and an underappreciated architect

Like so many other terms in art history, ‘roguery’ has turned out to have currency well beyond the scope envisaged by its progenitor. And also like so many other terms in art history, it has remained serviceable, despite the liberties that have sometimes been taken, because applying the necessary qualifications each time it is used would render it hopelessly cumbersome. Nevertheless, it needs to be regularly interrogated and re-examined in the context of the lecture for which it was coined. Goodhart-Rendel’s aim was to show that Victorian architectural history was full of figures who not only defied easy categorisation, but in some cases also confounded the assumptions on which established narratives were founded. Thus, John Shaw the Younger (1803-1870), for example, had pioneered the ‘Wrenaissance’ strand of the Queen Anne style with his (now former) Royal Naval College in Deptford of 1843-1844 a good 40 years or so before buildings that represent a locus classicus for it, such as Norman Shaw’s Bryanston in Dorset of 1889-1894. Alexander Thomson (1817-1875), following excursions early on in his career into the cottage orné and Scottish Baronial manners, had gone assertively neo-Greek right at a time when the Greek Revival appeared to be irrevocably on the wane. With his pamphlet of 1860 Victorian Architecture, in which he argued the need for a style that was an authentic expression of his own time, Thomas Harris (1829/30-1900) had done nothing less than devise a term to describe a whole era, yet in all other respects his venture had been a damp squib.

The transcript of the lecture manifests Goodhart-Rendel’s exceptional skill as a communicator – eloquent, witty, erudite and thought-provoking – and eye-witness accounts of those who were present when he spoke in public confirm the high expectations that it engenders of his delivery. It is a great pity that the text neither of this nor of his other lectures are, as far as I know, commercially available, meaning that they must be sought in major university or institutional libraries, something which at the time of writing makes them very difficult to consult. But without any such reservations I can direct anyone wishing to sample his writing to English Architecture since the Regency – an Interpretation of 1953, one of the best and most readable introductions to 19th century architecture that there is, based in part on lectures that he gave in the capacity of Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, a post he occupied from 1933 to 1936. I came across a copy during my first week or so as a Victorian Society caseworker in an Oxfam bookshop near the office, and although it is hardly a rarity (the National Trust reprinted the book in 1989 so fortunately there are plenty of second-hand copies in circulation which can be picked up for a very reasonable price) the discovery struck me at the time as nothing short of providential. Do indulge – it is a work I cannot recommend highly enough. Goodhart-Rendel possessed in ample quantity the most important skill of any good teacher of architecture – the ability to instil a desire to go and see for oneself the buildings that he describes.

All this is a remarkable achievement by any standards, and in the context of the time it is a very surprising one, since regarding Victorian architecture as worthy of serious study in the mid-20th century smacked decidedly of contrarianism. As I have discussed in a number of previous posts, perceptions of it have changed considerably in the course of the last 100 years or so, and it was not until well into the 1980s that the aesthetic and historical significance of 19th and early 20th century architectural heritage was sufficiently firmly established for it to be able to gain unassailable statutory protection. The battle was hard fought. That it was won at all was due to the efforts of pressure groups such as The Victorian Society, of which Goodhart-Rendel was a founding member, and the galvanising effect of major losses such as (in London alone) the Euston Arch, the Coal Exchange and the Birkbeck Bank. But all that is to anticipate, since at the time when Goodhart-Rendel was writing and lecturing, Victorian architecture in general and High Victorian Gothic in particular were viewed with profound distaste. Though Gothic died hard in the 20th century and the style remained current for ecclesiastical buildings until well into the 1950s, the work of the 1850s-1870s was strong meat for palettes of the inter-war period. The degree of revulsion can be gauged by the numerous examples of ‘de-Victorianisation’ such as the remodelling beyond all recognition of Aldwark Manor in North Yorkshire, featured in the post on E.B. Lamb’s country houses. Such examples are legion.

Even more remarkable than Goodhart-Rendel’s legacy as an author and lecturer is the fact that the architecture of the Victorian age closely informed his own work, for as well as being a scholar he was an architect in his own right. Yet though he occupied several influential professional posts – he was President of the Architectural Association in 1924–1925, President of the RIBA in 1937–1939, then Director of the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1936-1938 – within his own lifetime it attracted little attention and indeed sometimes met with incomprehension. It was prone to being overshadowed by his scholarship and when in 1955 he was appointed C.B.E., the citation read that it had been awarded ‘for services to architectural criticism’.

But he has been lucky to have an important advocate in architectural historian Alan Powers, who both edited and contributed to a collection of articles entitled simply H.S. Goodhart-Rendel, 1887-1959, published by the Architectural Association on the occasion of the centenary of his birth. It is still the nearest thing to a comprehensive monograph and an excellent source of information, not least because for several of Powers’ collaborators – such as John Summerson, who wrote the foreword – Goodhart-Rendel still existed in living memory. The illustrated catalogue of his works is particularly useful. But as is so often the case with books on architectural history, it had a small print run and unfortunately is now rare and correspondingly expensive on the second-hand market. More recently, Goodhart-Rendel has been well served by England’s Post-War Listed Buildings by Elain Harwood, a gazetteer handsomely illustrated with photographs by James O. Davies published in 2015. That any of the architect’s later work qualified for inclusion is a measure of how his stature has grown since 1971, when the first of his buildings – St Olaf’s House in Southwark, of which more anon – was listed.

Formative influences

Something now needs to be said about Goodhart-Rendel’s background and training. Born into a privileged and educated family – his father was a fellow in classics at Trinity College, Cambridge – he showed a keen interest in architecture from an early age. But his interest in music was equally strong and that was what he chose to study when he went up to Cambridge in 1905. He quickly attracted the attention of Lytton Strachey (to whose best known work the name of this blog alludes) and was briefly inducted into the Cambridge Apostles, although dropped when it became apparent that his interest in Christianity was no affectation. His degree was followed by a period of post-graduate study with the composer and musicologist Donald Tovey (1875-1940). It was not a success owing their antagonistic tastes: Goodhart-Rendel admired the French composer André Messager (1853-1929), famed chiefly for his light operettas and ballets, while Tovey revered the high seriousness of Johannes Brahms. Nevertheless, the friendship that they struck up survived unaffected, and when Goodhart-Rendel entered architectural practice after graduating in 1909, one of his first works was a house for Tovey’s former teacher and patron, Sophie Weiss (1852-1945) – The Pantiles, at Englefield Green in Surrey, built in 1911. Goodhart-Rendel never lost his interest in music and was reputedly an accomplished pianist who also composed a small amount, some of it published. In 1934 he became a governor of Sadler’s Wells and in 1953 vice-president of the Royal Academy of Music, which five years later made him an honorary fellow.

Yet Goodhart-Rendel’s architectural formation is rather more difficult to pin down. In 1909 he studied briefly with Sir Charles Nicholson (1867-1949), a prolific ecclesiastical architect who produced schemes (neither executed in full) for enlarging the old parish churches of Sheffield and Portsmouth after they were raised to cathedral status in 1914 and 1927 respectively. He also designed a large number of churches for new suburban areas and carried out numerous restorations, enlargements and reorderings of ancient buildings. Nicholson’s own training had been with John Dando Sedding (1838-1891) and he seems to have imbued his teacher’s belief that Gothic should be ‘living architecture for living men’, treating the style with such freedom that in later works it even absorbs thoroughly classical elements. All that postdates Goodhart-Rendel’s time in his office, however, and in fact with this one exception, the younger man was self-taught, which perhaps accounts more than anything else for his undogmatic approach. Lodestars included the great master of the English baroque Nicholas Hawksmoor (c. 1662-1736), on whom he published a study in 1924, and Arthur Beresford Pite (1861-1934), both figures who had stood outside the mainstream and produced no direct successors.

Muscular Gothic for the Roaring Twenties

Goodhart-Rendel’s early designs, for the most part domestic architecture, are handled in an elegantly spare astylar classical manner, sometimes reminiscent of Lutyens, sometimes – the result of devices such as fenestration arranged in bands and deep cornices – slightly of the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright. But the interest in Victorian architecture, though at that point dormant, was evidently there and it soom came to the fore in the work that he carried out at St Mary’s, Bourne Street in Belgravia, which I mentioned in passing in my post on R.J. Withers. St Mary’s had been established as a daughter church of St Paul’s, Wilton Place in Knightsbridge, and initially was a chapel-of-ease, ministering to a poor area on the boundaries of Pimlico and Belgravia with a population mainly employed in domestic service. It seems that the commission went to Withers on the strength of his work at the mother church, where in 1870 he had reordered what was essentially a late Georgian Gothick preaching box of 1840-1843 by Thomas Cundy Jr (1790-1867) to make it a more fitting setting for ritualist worship. It was a fortuitous choice: it put the project in the hands of an architect with an ability, so well demonstrated in his rural churches, to produce imaginative design on a limited budget.

St Mary’s became a stronghold of Anglo-Catholicism, but by the early 20th century this no longer implied sympathy for Gothic, instrumental though the movement had been in its development throughout the preceding century. High Churchmen began to turn their back on the style and instead embraced Italianate and Iberian High Baroque, a measure not only of changing tastes, but also of increased freedom which now allowed devotion of a kind that, only a short while earlier, would have invited charges of crypto-papism. As early as 1908, Sydney Gambier Parry had designed for Fr Howell, the then-incumbent, a reredos and an organ loft in an exuberant brand of loosely English Baroque. In 1916 Fr Humphrey Whitby became parish priest. He engaged to continue the work of refurnishing the building Martin Travers (1886-1948), who had previously carried out work for him at St Columba’s, Kingsland Road in Haggerston (one of James Brooks’s mission churches to the East End), where Whitby had been a deacon prior to his appointment. Travers was kept busy with commissions for St Mary’s into the early 1920s, providing a number of flamboyant gilt fittings that worked well as an ensemble in their own right, but were profoundly at odds with Withers’ architecture. It was at any rate a mercy that Travers did not whitewash the interior, as he did at Butterfield’s church of St Augustine, Queen’s Gate to set off better the equally extravagant fittings that he designed for that building.

Whitby was independently wealthy and willing to put his means at the service of the parish. His plans for the building went a long way beyond refurnishing and embellishment, and here he ran up against Travers’ great disadvantage for ambitious clients such as he – a lack of any formal architectural training. Goodhart-Rendel’s own churchmanship at this date was Anglo-Catholic and this, as likely as not, explains why he was brought in when, around 1922, Whitby decided to remodel ‘The Pineapple’, a pub on the corner of Bourne Street and Graham Terrace, as a presbytery. Goodhart-Rendel rose to the occasion with a spirited piece of Arts and Crafts, slate-hung in the vernacular tradition of Devon and Cornwall, and from some angles upstaging Withers’ church in the streetscape. This seems to have stood him in good stead when a competition was held in 1924 to find a design for the enlargement of the church into a vacant strip of land that adjoined it to the (liturgical) north. He added an outer north aisle to serve as a Lady Chapel, with an altar dedicated to the Seven Sorrows of Mary.

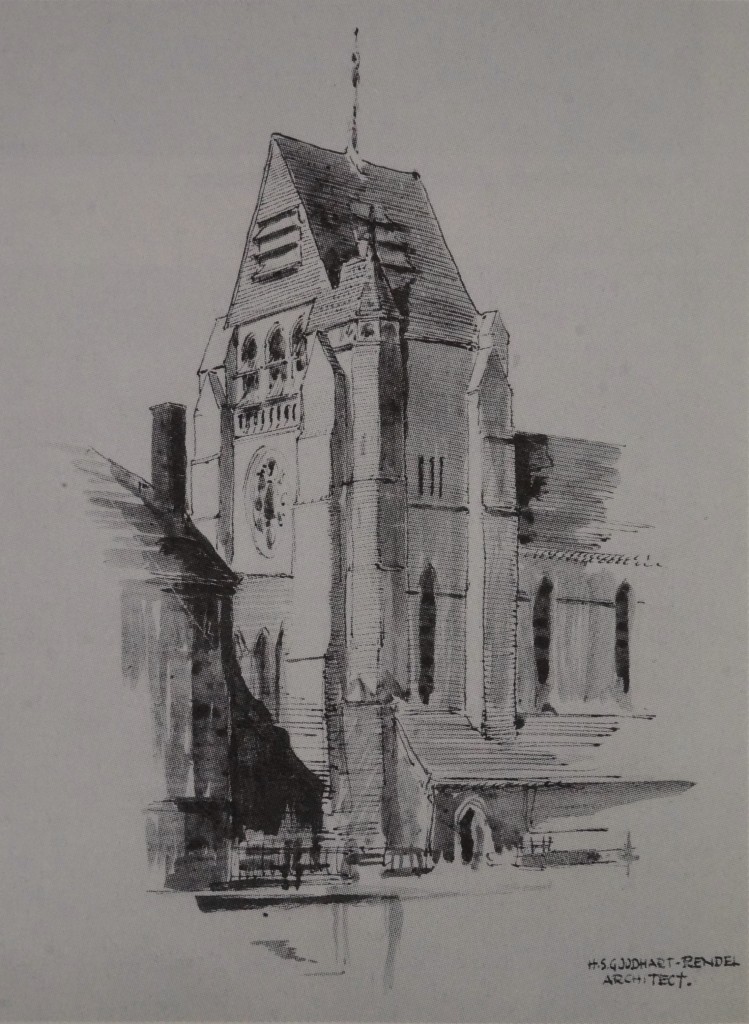

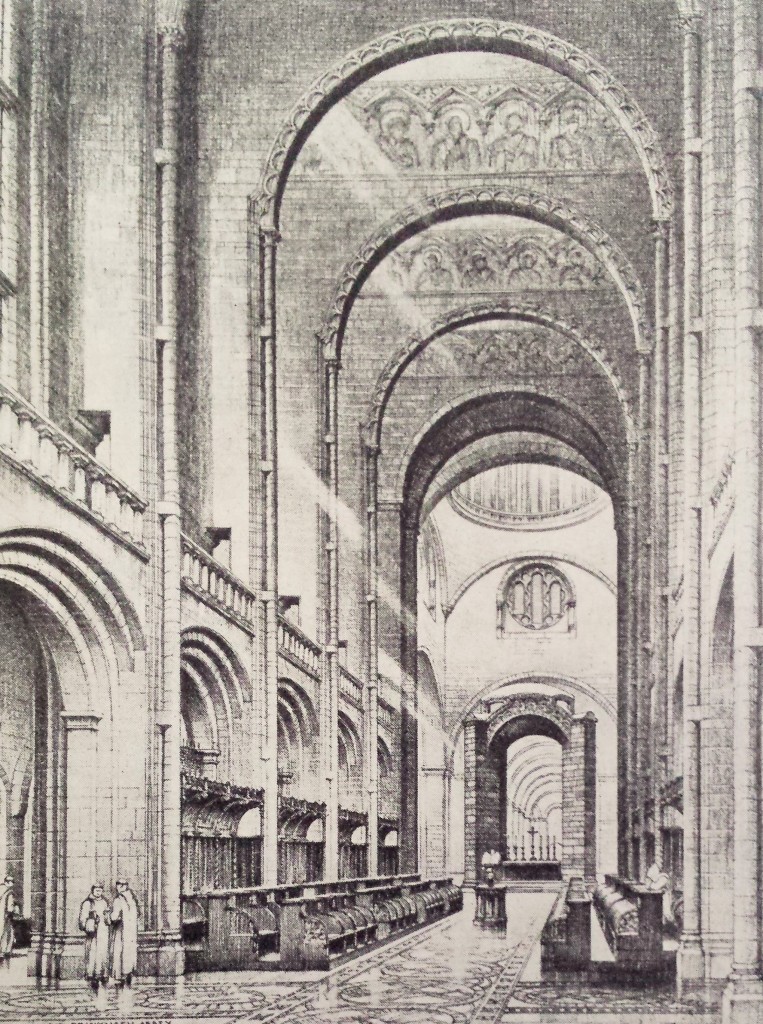

Though liturgically subservient to the main worship space, spatially it is not so since it forms part of a new access route to the interior. It is elongated to the liturgical west with a narthex linking it to an ingeniously contrived two-storey heptagonal porch. This is approached down a narrow passage running between the presbytery and neighbouring residential property, opened up by the demolition of a house that had previously occupied the site. Whereas Travers had shown complete disregard for Withers’ architecture, Goodhart-Rendel responded with great sensitivity: his undemonstrative but subtly detailed Gothic with beautifully executed brickwork is perfectly consonant with it, and the visitor’s progress from the street outside to the interior instils both mystery and drama as a succession of spaces unfolds, all varying in width, height and the level of lighting. The final stage of the journey from the Chapel to the nave though a north aisle with vistas opening up in two directions is a real masterstroke. The architecture is equally carefully conceived in relation to the fittings designed for it – a reredos painted by Colin Gill (1892-1940), altar rails by Betty Joel (1894-1985) and stained glass by Veronica Whall (1887-1967). In 1929, Goodhart-Rendel added a servers’ sacristy on the south side of the apse, but a powerful design for a west tower with a saddleback roof unfortunately remained on paper. This is the first instance of a device that became one of the architect’s trademarks. It had been favoured by William Butterfield (1814-1900), and it says much that in English Architecture since the Regency the author reproduced an engraving by Beresford Pite of that architect’s church of St Alban’s, Holborn, where it had been employed, which depicted the tower rising dramatically out of a squalid and devastated urban setting.

An excursion into modernism

It is important to stress that Goodhart-Rendel was not a niche pasticheur, and no building demonstrates that quite so cogently as what is perhaps his most celebrated work, St Olaf’s House on Tooley Street in Southwark. It was built in 1930-1932 as the headquarters of Hay’s Wharf, a company originally set up by Alexander Hay in the 17th century. At one time this owned all the warehouses on the south side of the Thames between London Bridge and Tower Bridge, which were used for storing freight arriving at the Pool of London, and it also operated related and equally lucrative businesses, such as shipping and distribution services. Though the current name of this building is relatively recent (it dates from when Hay’s Wharf vacated the premises in 1986), it reflects the long history of the site, which was formerly occupied by the church of St Olave’s, Tooley Street, a medieval foundation rebuilt to the designs of Henry Flitcroft in 1738-1739 and demolished in 1926-1928.

Nothing in the architect’s output from before that date quite prepares one for St Olaf’s House, and indeed the design did not emerge from Goodhart-Rendel’s head fully formed, instead evolving through a series of concept sketches which were initially neo-classical. The building defies easy categorisation and represents a very different response to the gauntlet thrown down by the European avant-garde to what a slightly younger generation of architects, such as the Connell, Ward and Lucas firm, was doing around this date. Of all the stylistic labels attached to it, the only one that describes it adequately is ‘Moderne’. Like Art Deco and unlike Functionalism, it is able to incorporate applied art and ornament, but with greater seriousness of purpose than the Jazz-age decorative trimmings to be found in the former. There is even a touch of the expressionist Amsterdam School in the angularity of some of the modelling. The oriel windows overlooking the river that light the common room and double-height board room are adorned by gilded faience panels mounted on polished back granite entitled ‘The Chain of Commerce’. These were the work of Frank Dobson (1886–1963), who was also responsible for the outline figure of St Olave in black and gold mosaic on the landward side.

While there are other buildings of this date with superficially modernist trappings such as strip windows, metal-framed glazing and smooth Portland stone cladding, here a powerful intelligence has grasped something much deeper than just a set of mannerisms. Goodhart-Rendel was keen to rise to the intellectual challenge of the Modern Movement, but also to engage with it on his own terms. The stanchions on which St Olaf’s House is supported have as much to do with a requirement in the brief for vehicular access to the waterfront and a covered area for cars to drop off passengers by the entrance as they do with the notion in Le Corbusier’s ‘Five Points’ of liberating a building from the ground by raising it up on pilotis. The angular modelling of the forms is no stylistic affectation, but dictated by the need to maximise the amount of light that could be brought into the drawing offices on the sixth floor. The load-bearing steel frame is clearly expressed in the elevation to the river, yet the source of Goodhart-Rendel’s theories of structural rationalism was Viollet-le-Duc, who in turn claimed to have derived them from his study of the architecture of the 12th-13th centuries. The architect was therefore not being wholly flippant when he replied, having been asked to describe the style, that it was ‘early French Gothic’.

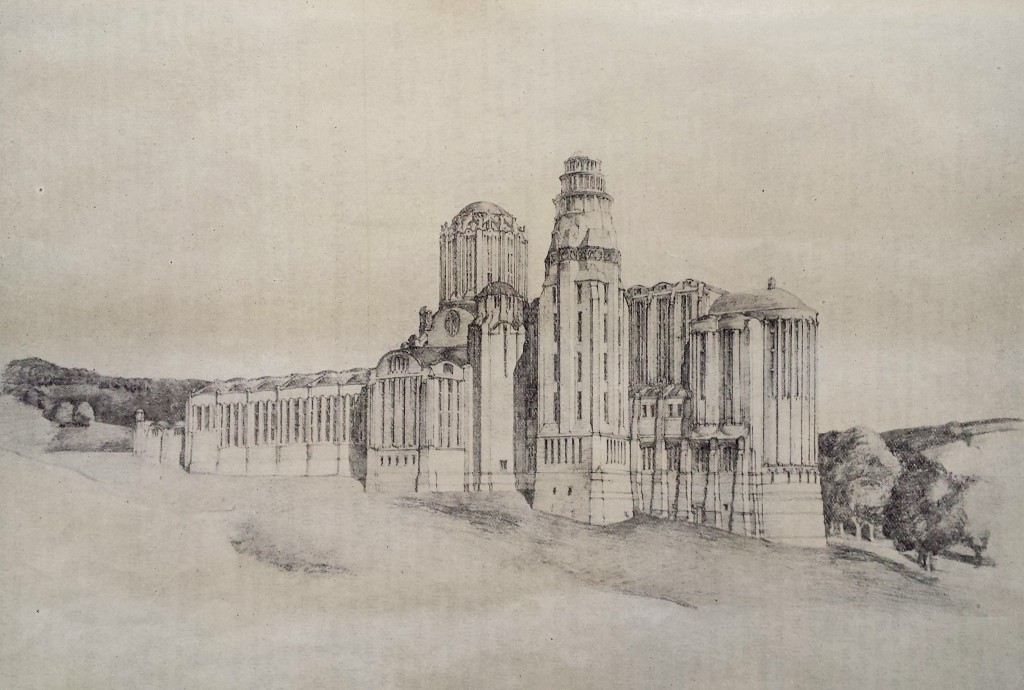

In 1924 Goodhart-Rendel converted to Catholicism, and the churches that he built for his faith are among his most important and characteristic works. But what would have been the greatest of them all was fated to remain on paper. Prinknash Abbey was founded in 1928 by a community of Benedictine monks which had previously been based on Caldey Island off the Pembrokeshire coast near Tenby, and which had converted from Anglicanism to Catholicism in 1913. They took up residence in a stately home southeast of Gloucester that until the Dissolution of the Monasteries had been a grange of St Peter’s Abbey, the establishment that Henry VIII turned into Gloucester Cathedral. This was the bequest of another fervent Catholic convert, yet it was only a temporary expediency and around 10 years later, Goodhart-Rendel was engaged to produce designs for a purpose-built complex. It was to be a major statement of Catholic triumphalism – the immense abbey church would have stretched to 300ft (91.4m) in length. Its very construction was to be an act of devotion, since it was intended that the church would be built by the monks and thus the walls were to be solid masonry, finished in honey-coloured local stone. The vaults and domes were to be mass concrete, clad externally in copper.

The transverse barrel vaults of the choir were inspired by those of the Romanesque church of St Philibert at Tournus in Burgundy, yet used not for aesthetic effect but to avoid the need for external buttressing. Gothic was abandoned altogether in favour of a highly personal stylisation of Byzantine architecture. This harks back to Westminster Cathedral by J.F. Bentley (1839-1902), a figure deeply admired by Goodhart-Rendel, and perhaps also to the equally sophisticated reinterpretation of the style by Beresford Pite at Christ Church, Brixton. The design went through several revisions and the final version did not appear until 1953. Ground was broken that year, but it quickly became obvious that completion in line with the architect’s full intentions was unrealistic. The lower crypt chapel, where Goodhart-Rendel was buried, was fitted up as a temporary abbey church, then in the 1960s a much scaled-down scheme housing the entire monastery was built on what had been completed of the foundations.

Rebuilding Victorian Britain

In fact the most exciting opportunities for building new churches came not from the Catholic revival but post-war reconstruction, when Goodhart-Rendel’s ability to respond sensitively to Victorian fabric properly came into its own. One such instance was St John the Evangelist, Maze Hill in St Leonards-on-Sea, one of a number of large town churches built in the latter part of the 19th century as this then-prosperous East Sussex resort underwent rapid expansion. The architect was the prolific Sir A.W. Blomfield (1829-1899), who handled a large number of such commissions and supplied what seems to have been a fairly typical product of his office, which was completed in 1884. Its most distinctive feature was the slender octagonal tower. In February 1943 a high explosive bomb destroyed everything apart from that and the adjoining west wall and baptistery. Reconstruction began in 1950. The nave was finished in 1952, followed by the chancel in 1957, when the building was re-hallowed, although work on some of the ancillary features continued into the 1960s.

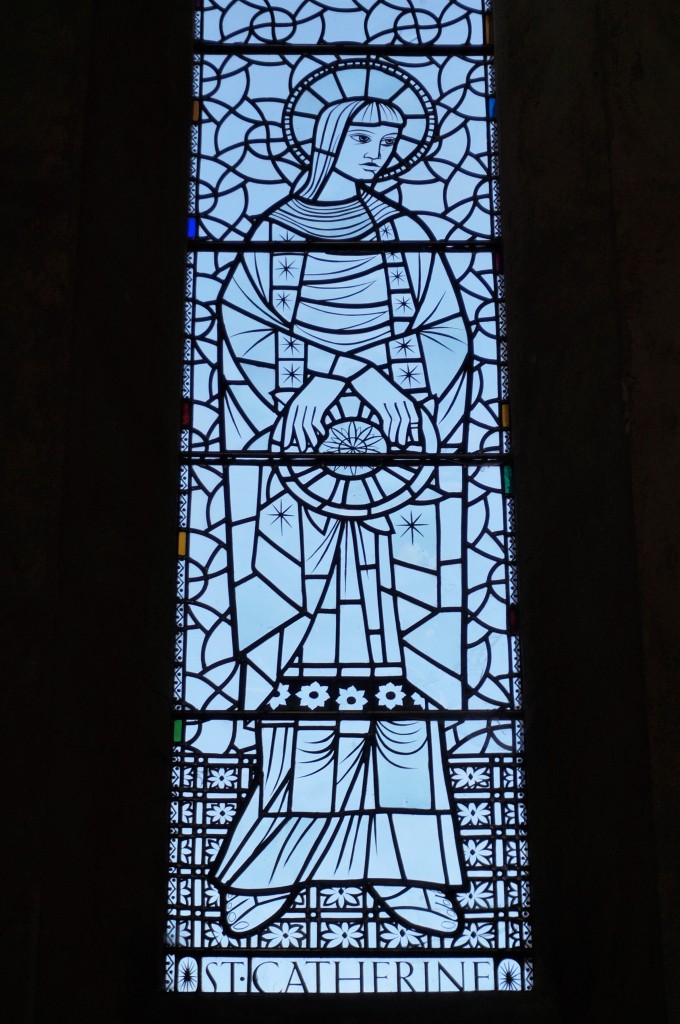

The church is unusual in Goodhart-Rendel’s output for being explicitly Gothic. Though usually inclined not to use pointed arches, which he disliked, nevertheless he was keen to harmonise with what had been retained of the original fabric. Essentially, the building is a large single vessel of broad, lofty nave, with low passage aisles, and only slightly lower and narrower chancel. But great drama and interest are introduced at the junction of these two volumes. A flying arch originally intended to carry the organ and seating for the choir spans the chancel arch about half way up. To either side are unusual openings of one and a half bays into transept-like spaces, which in turn lead through to the side chapels flanking the chancel. Above them are short stretches of clerestory-like fenestration providing lighting from the side and above. The baptistry and font of the Blomfield church were retained and incorporated into the new building, with vividly coloured stained glass by Margaret Thompson (1909-2007) to replace what had been lost. Elsewhere the glass is the work of Joseph Ledger (1926-2010) who supplied unusual designs that are largely monochrome with sparingly, although very effectively deployed spots of colour. Externally the church is powerfully modelled and clad in superb quality brickwork with plum-coloured banding. The almost vernacular treatment of some of the roofing, which incorporates gambrels and catslides, belies the grand scale of the building and maintains visual subservience to Blomfield’s tower.

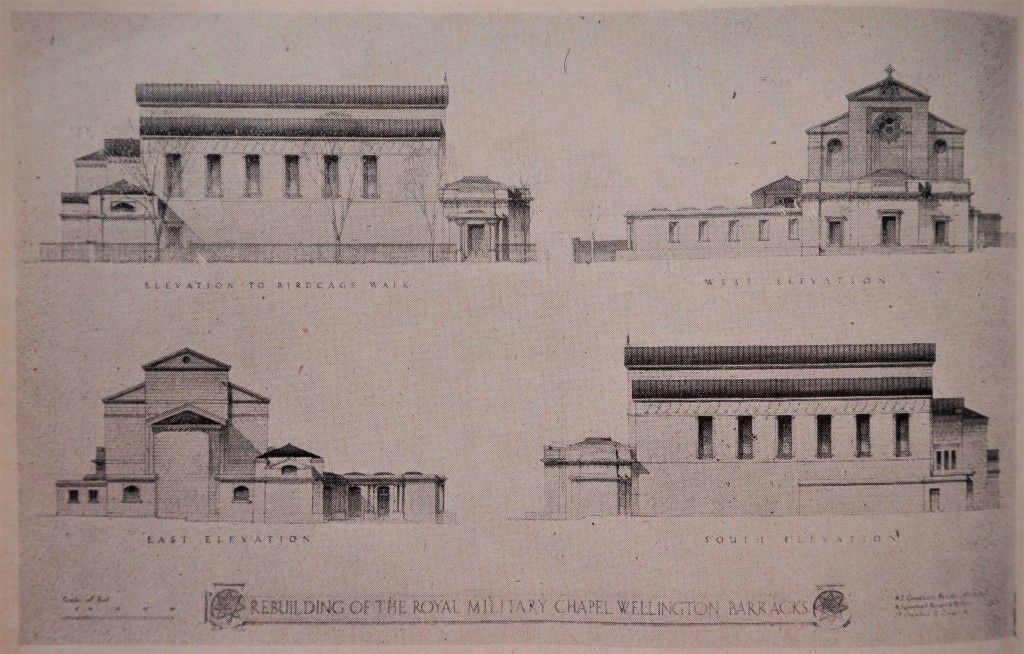

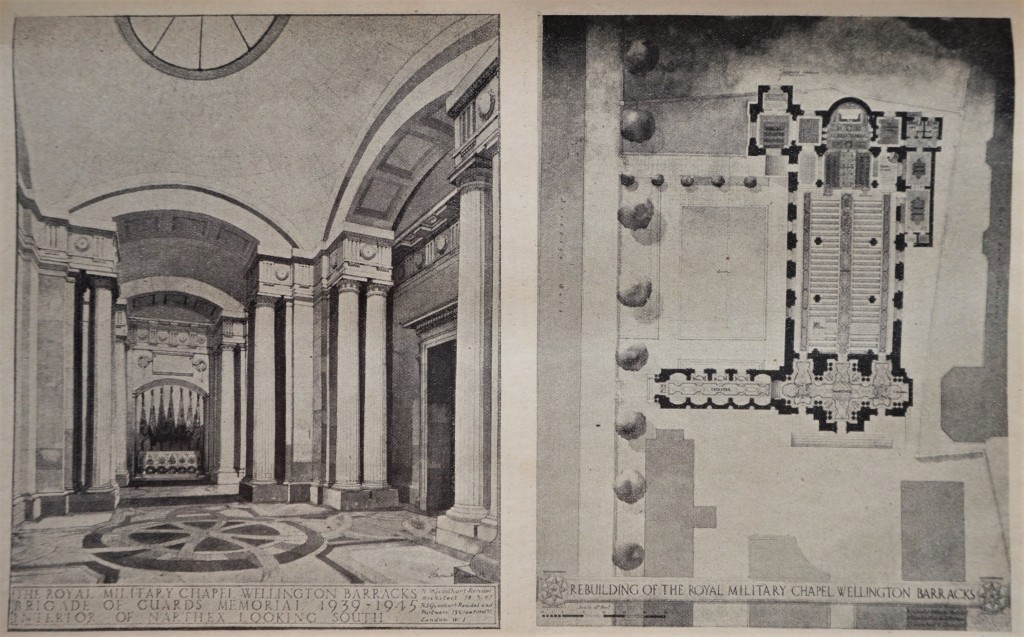

Fortunately, the destruction of St John’s did not claim any human life. The same was not true of the direct hit by a V1 rocket bomb of the Guards’ Chapel at Wellington Barracks in Westminster. When it occurred on 18th June 1944, a service was in progress and 120 people were killed. The commission to rebuild the chapel must have had special resonances for Goodhart-Rendel, who had been an officer in the Grenadier Guards and confided to James Lees-Milne in 1942 that his devotion to the army came second only to that to the Roman Catholic church. The scheme was drawn up quickly and published in The Builder of 12th December 1947. Though Goodhart-Rendel’s response to the character of place was usually exceptionally perceptive, it is difficult not to get the sense that this job caused him a certain amount of difficulty. This was perhaps the result of the unusual circumstances, since the old chapel had been a not entirely happy amalgam of wildly contrasting styles. Built in 1838, possibly to the designs of Sir Frederick Smith of the Royal Engineers in consultation with Philip Hardwick (1792-1870), it was a temple-form building with a Greek Doric portico. As built, the interior was reportedly very plain and in 1876 a committee was formed to beautify it, to which end it engaged G.E. Street (1824-1881).

The scheme, completed in 1879, involved the insertion of round-arched arcades and addition of an apsidal chancel in the Italianate Romanesque manner that enjoyed great popularity for military places of worship. The interior was vaulted with alternating ribs of Bath stone and Roman red brick and it was richly decorated. Much of this was the work of Clayton and Bell, who supplied the stained glass and designed the sumptuous mosaics in the sanctuary, which were executed by Salviati. Though the effect of the explosion was devastating, it had left the apse largely intact (reputedly candles lit during the service were still burning when the dust had settled) and it was desired to retain this. Goodhart-Rendel’s design was based on reusing the existing foundations and followed the forms of the pre-war building fairly closely, although it supplanted Street’s neo-Romanesque detailing with overtly classical devices, such as Composite order pilasters and guilloche mouldings to the soffits of the arches. The Doric portico was omitted in favour of a cloister arm extending out at a right angle to a new entrance on Birdcage Walk. This was to be wholly classical in manner, consisting of a series of vaulted chambers with space for monuments to the regiments of the Foot Guards and Household Cavalry, and it was to culminate in a grand narthex enclosing the main entrance to the chapel proper. In the event, only the cloister arm was completed and that not until 1956. The architect’s death seems to have brought the project to a halt and when work recommenced, an uncompromisingly modernist design by Bruce George was substituted, which was eventually completed in 1963.

More successful was Goodhart-Rendel’s restoration of another major work by G.E. Street, the church of St John the Divine in Kennington, south London. That architect’s largest church in the capital, capable of seating a congregation of 1,000, it was built in stages in 1871-1874. The building consists of a broad and lofty nave and aisles with no clerestory and the easternmost bays of the arcades are canted inwards where this huge volume narrows at its junction with the chancel. At the west end is a tower and spire soaring in height to 212ft (64.6m), completed posthumously in 1887-1888 under the guidance of the architect’s son, A.E. Street. An incendiary bomb which hit St John’s in 1941 caused severe damage and the building was entirely gutted, as recorded in a photograph in the RIBA collection. In his reconstruction of 1955-1958, Goodhart-Rendel skilfully reinstated the roof on the basis of Street’s drawings, omitting the later, unsympathetic decorative scheme that had been added in the 1890s by G.F. Bodley (1827-1907). He brought forward the altar from the apse, introducing a dais at the west end of the nave, which was flanked with wrought iron screens emulating Street’s own superb work in the medium. Goodhart-Rendel showed equally sure command of the Victorian master’s idiom in his design for the neighbouring complex at Nos. 92 and 96 Vassall Road, originally built in 1952-1954 as a convent and lodge for the Community of St Mary and now used as a vicarage and caretaker’s house.

War damage produced yet another major ecclesiastical commission – the reconstruction of the church of Most Holy Trinity, Dockhead on Jamaica Road in Bermondsey. The parish traced its origins to a mission established in 1773, whose chapel was destroyed in the Gordon riots of 1780. This was rebuilt but quickly outgrown, and so was replaced in 1837-1838 by Sampson Kempthorne (1809-1873), who provided a large aisled and galleried brick building in a rather bald lancet style. In March 1945, a flying bomb destroyed both this and the adjoining convent of 1838 by A.W.N. Pugin, his first such commission. In 1957, work began on the replacement church with its attached presbytery, which was not completed until 1960. In contrast to the works described above, Goodhart-Rendel responded to the commission in a manner that marked a complete departure from the character of the original church, which in any case had stood on a completely different site that was largely obliterated by post-war traffic improvements.

The geometry of the design is organised around equilateral triangles, interpreted as a symbol of the Holy Trinity, and the hexagon, of which they are a constituent element. This is most apparent in the powerfully massed towers of the entrance front, hexagonal in plan and flanking a central arched opening. The device had been used by German architect Theodore Fischer (1862-1938) at his Pauluskirche in Ulm of 1908-1910 (although there the towers are circular rather than polygonal) and a comparison has been drawn on several occasions, although whether Goodhart-Rendel was explicitly inspired by that building is unclear. But for all the intellectual games in the planning and proportioning, what sticks in the memory about the exterior is the direct, very sensual appeal of the constructional polychromy, a dazzling array of stripes, interwoven diagonal banding and reticulation in beautifully executed plum, crimson and steel-blue brickwork, bold and vivid enough to rival Victorian gothic of the 1850s-1860s at its most strident. This is subtly echoed by the geometrical patterning of the leadwork of the plain glass in the lunettes of the nave windows. A towerlike mass with a transverse saddleback roof is heaved up above the chancel to light the space from the sides and above (here, the east window is tiny), a reinterpretation of the device already encountered at St John the Evangelist in St Leonards-on-Sea and used at several other churches.

The stately interior has tall passage aisles and transverse vaults of thin concrete. This, together with the concentration of lighting from the south (the north side of the nave is mostly blind) represents the realisation of ideas first tried out in the unexecuted scheme for Prinknash. But whereas there the transverse vaults were to have been horizontal in section, here they rise to follow the curve of the arches that bridge the central aisle. The colour scheme of the interior is relatively muted compared to the exuberant display of the exterior and constructional polychromy is confined to the chancel, where the lower part of the sanctuary is clad with tiers of pilasters on a banded ground of cream and buff stone, incorporating ceramic reliefs by Atri Cecil Brown (1906-1982). The same artist perhaps was also responsible for the monogram of the Trinity set into the east wall, located above the carved and gilt canopy with its coffered soffit; certainly he was responsible for the Stations of the Cross, which were installed in 1971. The banding reappears on the curved front of the built-in pulpit. The tactical use of colour concentrates the worshipper’s attention on the liturgically most important part of the building, although this feels a little overwhelmed by the slightly threadbare overall impression. The pilasters in the sanctuary are fluted and the top cornice incorporates a strange paraphrase of dentilation – one of the few parts of the building capable of being analysed in these terms. Everywhere else, though the reminiscences of historical prototypes – be they Roman, Romanesque, Gothic or Classical – are strong, the effect is to tease rather than to evoke, always allusion rather than direct quotation. The relationship to historicism is every bit as ambiguous as that of St Olaf’s House to modernism.

Conclusion

After Goodhart-Rendel’s death, his practice was taken over by Frank Broadbent (1909-1983), his former business partner. H. Lewis Curtis, his former assistant, oversaw the completion of projects such as Holy Trinity, Dockhead, ensuring that this was done in accordance with his intentions and succeeding admirably in imitating the master’s style when additional design work was required. Otherwise, most of what Goodhart-Rendel had represented died with him. His death occurred at a pivotal moment for British architecture: modernism was finally emerging triumphant from the stylistic pluralism that had persisted for much of the 20th century, which in the ecclesiastical sphere was marked by the victory of Basil Spence in the competition of 1951 for the new Coventry Cathedral. Though aspects of the planning of that building were decidedly conservative, the reforms of the following decade initiated by the Second Vatican Council in the Roman Catholic Church and the liturgical movement in the Church of England would propel ecclesiastical design towards greater innovation and more decisive breaks with historical precedent.

Though traditionalism never quite died out, those architects who persisted with it would from now on plough a lonely furrow. The milieu in which it remained in demand was ever more tightly circumscribed – additions to historic buildings in sensitive locations, commissions from wealthy clients with conservative taste. Goodhart-Rendel had known from his own experience how unfashionable Victorian Gothic had been in the middle decades of the century; now any revival at all of a past style looked retrogressive, if not downright reactionary. Post-war classicism was fortunate to have at its service such talented practitioners as Sir Albert Richardson (1880-1964), Raymond Erith (1904-1973) and Sir Clough Williams Ellis (1883-1978), but Gothic wanted for comparable advocates. At St John in Newbury, Berkshire (designed 1950, built 1954-1957) and The Good Shepherd in Arbury, a suburb of Cambridge, Stephen Dykes Bower (1903-1994) had looked to be pursuing a similar line of development to Goodhart-Rendel, not least in his celebration of colour and craftsmanship in brick. But these turned out to be isolated instances: elsewhere, it was the cool, refined Gothic as practised by the likes of G.F. Bodley and Temple Moore in the 1880s-1900s, not the colourful stridency of the 1860s, that served as his inspiration.

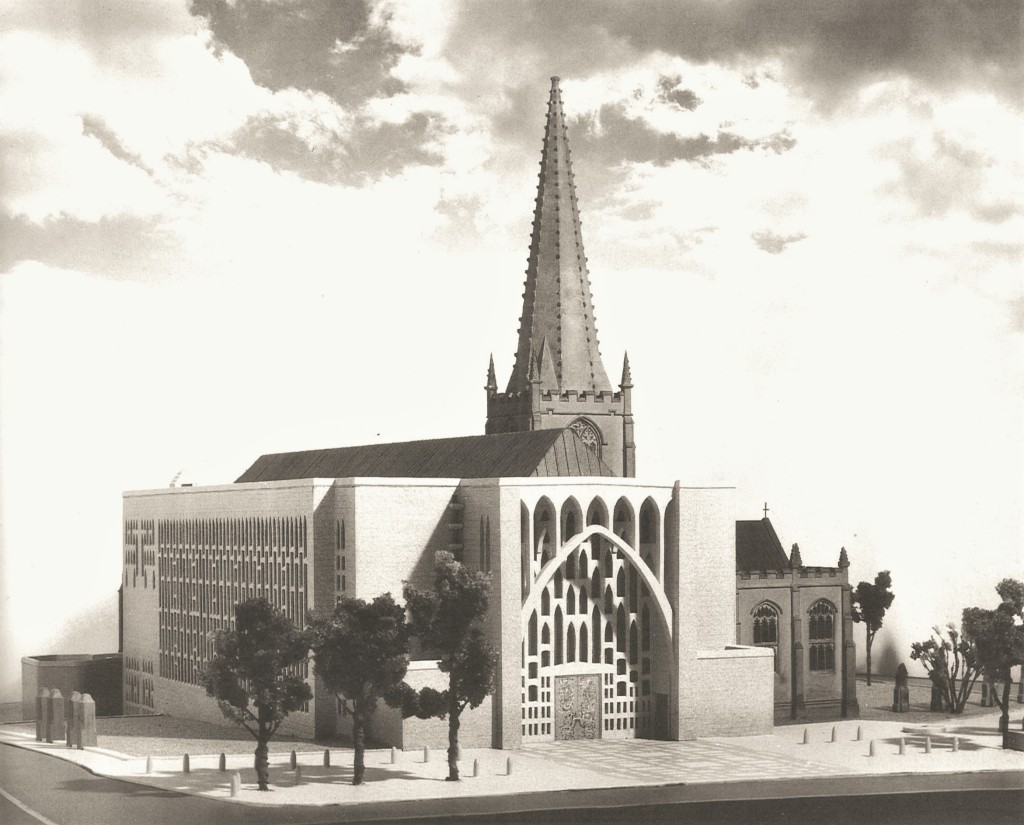

George Pace (1915-1975) remained truthful to the Arts and Crafts ethos in his emphasis on handicraft in a wide variety of media and meticulous detailing, all in the service of a total aesthetic, and to some degree he perpetuated the spirit of Gothic in his numerous ecclesiastical commissions. But he reembodied it in an often uncompromising Modernist aesthetic, whose kinship with the architecture of High Victorianism was to be found mainly at a conceptual level in its stridency and muscularity. Where he used the pointed arch, it was usually because of the need for a measure of visual deference to existing fabric, such as in his unexecuted designs of 1956-1961 for the completion of Sheffield Cathedral, which had to knit together the retrochoir and choir aisle – all that had been completed of an monumental neo-Gothic scheme by Sir Charles Nicholson begun in 1936 and curtailed by the outbreak of World War II – with the eastern arm that was to be retained of the city’s originally medieval parish church as a kind of outsize transept. Even more startling than this already visually arresting conception is the west front added when the nave was eventually completed in 1966 to a scheme by Ansell and Bailey. It has distinct affinities with the most wilful roguishness of 100 years earlier, paraphrasing the forms in a manner that can only be described as Brutalist Gothic.

Victorian architecture might have benefited from critical reassessment and growing appreciation as the 20th century wore on, but that did not make neo-Victorianism a popular cause. Nor was it much buoyed by the reaction against modernism in the 1980s and campaign for a return to styles of the past led by Prince Charles, the effect of which was largely to reanimate the corpse of the Neo-Georgian movement. There are, however, some honourable exceptions. One is the later work of William Whitfield (1920-2019), who, at a speculative development for the Crown Commissioners in Pimlico, explored the possibility of reviving load-bearing masonry construction and in so doing produced an office block quite unlike any other with its overtones of the industrial architecture of the 19th century – inescapable, even if the architect himself denied that that had been the intention. At the Whitehall frontage of Richmond House of 1982-1984, he cleverly reinterpreted the forms of Tudor Gothic to give greater emphasis to a façade occupying an awkward site, as well as alluding to the lost Holbein Gate of Whitehall Palace, which had once stood nearby. In both designs he rejoiced in craftsmanship and the colour and texture of his materials to a degree quite exceptional for the date. The Queen’s Building at De Montfort University in Leicester by Short Ford Associates of 1991-1993 evidences not only a similar delight in constructional polychromy, but also combines it with the pointed arch, as well as exploiting functional demands – here, aimed at facilitating natural ventilation – to create expressive forms in a manner that would have thrilled the likes of Charles Henry Driver.

I cannot help thinking that the dearth of heirs to Goodhart-Rendel in some respects springs from the failure of many architects to see the continuation of older traditions as being motivated by something much more profound than an unending Battle of the Styles. The key to this is St Olaf’s House. It is remarkable not only in Goodhart-Rendel’s own output but also in the context of the time. Architecture has always tended to be tribal, but at few times more so than in the 20th century, when the rise of modernism sharply polarised the profession. You could be, say, a Neo-Georgian who occasionally dabbled in Gothic, but if you were a traditionalist then you were not supposed to stray into the territory of the rival camp. That Goodhart-Rendel did is because of his unique mindset, which married a rationalist outlook to a certain scepticism. When at Hays Wharf he adopted an architectural language that clearly owed nothing to any century other than the twentieth, he did so because it suited his requirements for meeting the brief rather than out of evangelical fervour. Despite its success, he remained ambivalent about the very notion of modernism. ‘New or old in style? It will all soon be old, and neither better nor worse for that’, he replied when asked for his view of the Exhibition of British Art in Industry of 1935.

Yet his view of the architecture of the Middle Ages and, one infers, the 19th century was every bit as guarded. ‘Only those forms shall be embodied for which the reason is still completely valid’, he said of the design for Prinknash Abbey. ‘All styles of the past are to be ignored, except insofar as the causes from which they spring are still active’. Goodhart-Rendel’s architecture is unpredictable: each one of his buildings is a fresh response to the challnges posed by the commission and the site, each design represents the fruit of serious consideration of the relation of plan, function and structure to form. Style is attained as part of the solution to the brief; it is not a veneer to be applied at will to dress up construction. Even if a familiar language is employed, it is manipulated to express new ideas. To engage with and reinterpret for the modern age the legacy of the 19th century involves engaging with it at a conceptual level. So too, of course, should doing likewise for the classical language of architecture, but that, for better or for worse (and usually the latter), is more easily reduced to a series of formulaic devices and details. This more cerebral engagement remains a rare approach among British architects working in a traditionalist vein. The few practitioners who have attempted it have all been gadflies and the results of their efforts highly idiosyncratic, with no imitators among their peers or followers among the succeeding generation. Thus it is that the historian of the Victorian ‘rogues’ showed himself to be one of their own kind. It is an outcome that might well have pleased the man himself.

2 thoughts on “H.S. Goodhart-Rendel and the 20th century Victorians”