It’s been over two years since I last posted anything here. But that’s not because my interest in Victorian architecture has in any way diminished. Instead, I’ve redirected my time and effort towards a number of other projects in architectural history . The biggest so far is a book that has just appeared in print, and if you enjoy the blog then I think you’ll enjoy this. It covers the life and work of three architects who have featured here in the past – R.L. Roumieu, Joseph Peacock and Bassett Keeling. You can buy your copy directly from my publisher, Liverpool University Press, here.

It’s just possible that somebody here might remember that the post on Joseph Peacock was intended to mark the inception of work on a book (it was published in March 2021, so anyone who doesn’t can be forgiven). It so happened that I wrote a proposal for a monograph on that architect shortly before starting ‘Less Eminent Victorians’. Two COVID lockdowns intervened between my submitting it and Liverpool University Press approving it. Of course, I was pleased to be given the go-ahead, but by that point nagging doubts had set in. Indeed, one of the editorial board had inadvertently picked up on them by wondering out loud if Peacock was really a sufficiently important architect to warrant a work of 40,000 words devoted exclusively to him. By March 2021, having roamed far and wide through Britain’s Victorian heritage for this blog, I was inclined to agree. It seemed like a wasted opportunity not to expand the scope.

I carried on exploring other figures throughout the rest of 2021. At the end of that year I moved to Suffolk to start a new job. Once the dust had settled, my thoughts returned to the book project and I hit upon the idea of examining alongside Peacock the two other architects who, together with him, make up what H.S. Goodhart-Rendel had dubbed in his lecture of 1949, Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era, ‘a trio of architectural rakes’. These were the practitioners whom he regarded as having produced the wildest, most flamboyant and wilful emanations of High Victorian Gothic, transforming by virtue of their Roguish temperament – by Goodhart-Rendel’s definition all of the Rogues shared ‘a fairly savage temper architecturally’ – a style that was already strong meat to start with. This opened the door to a study not just of two more architects, but of a whole chapter in Victorian architectural history that has intrigued me since my early teens.

It’s important to stress that Roumieu, Peacock and Keeling all worked independently of each other. Though there are points of contact and even places where their careers interweave (although you’ll have to read the book to discover them), the idea that they deserve to be considered together on the grounds of a shared aesthetic belongs to Goodhart-Rendel. But I realised that their similar lifespans and outputs made it likely that splitting the book three ways between them – essentially, one chapter per architect – would work well. My commissioning editor was happy to entertain the idea, for which I am very grateful, and said that, if I were to write a proposal, she would be happy to submit it to the editorial board to be approved. I did and it was during the summer of 2022.

The rest of that year and most of 2023 were taken up with work on the book. Though I had laid the foundations of the chapter on Roumieu with my blog post on him, it was written during the third COVID lockdown when there was no question of conducting any primary research. I knew that there were numerous gaps in his works list to be filled and that I could not start work on that chapter until I had filled out the record of his career. My research enabled me to identify positively for the first time a lot of his drawings in the RIBA Collection that were catalogued under generic descriptions. I spent a session there during the spring of 2022 looking through all their holdings on Roumieu and to inspect closely the truly lovely draughtsmanship of what are, for the most part, high quality presentation drawings was pure enjoyment. Some of his commissions turned out to be very obscure, and I drew a complete blank on a small number, such as the remodelling of the apparently Stuart or early Georgian Itchel Manor, Crondall in the north of Hampshire, which I still haven’t been able to date.

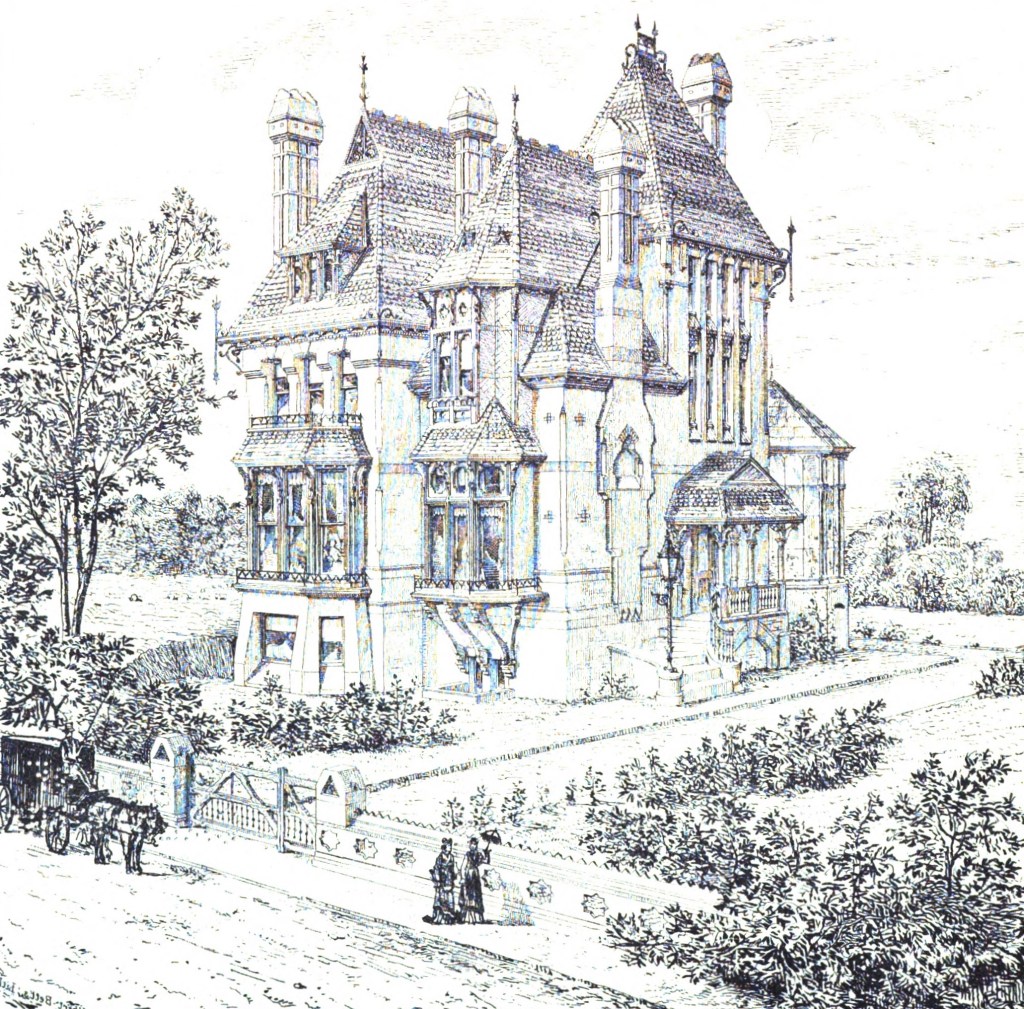

It is mentioned in Roumieu’s obituary in The Builder, and an archive photograph of the house (it was demolished in 1954) shows some Victorian Italianate bay windows and a rather fine conservatory that might well have been his work. Was it a major commission? On the basis of this scant information – there seem not to be any leads in the county record office – perhaps not, although I am happy to stand corrected if anyone can add to my knowledge. It would have been interesting to pursue my enquiries further, but with research like this it is easy to fall down rabbit holes and end up wasting time and energy that are disproportionate relative to the amount of information that they eventually yield. Some lost buildings, alas, have simply not left all that much of a paper trail. An image of another country house job by Roumieu is included here. It deserved to be reproduced in the book, but the quality was insufficient. Screen resolution is more forgiving and so it appears here instead.

My Master’s dissertation on Peacock written back in 2014-15 had provided almost all the material that I needed to give an account of my second subject’s life and work. A few more snippets of information came to light while I was doing my research and they have been incorporated. Completely recast and much compressed, the dissertation now fits into a chapter and, I think, is ample to do him justice. When I was writing it, compiling the works list and tracing the subsequent history of all the commissions was a major effort – and that to say nothing of the fact that all this had to be done not only in parallel with a full-time job, but also while changing employers, getting used to a completely new line of work in heritage consultancy, and dealing with a house move that was forced on me. I was flushed with pride at the time with the end result, but too tired and under too much pressure to attempt the critical appraisal that was really needed. Following my viva, I was given special dispensation to append one, but over time felt that I had not quite hit the mark with it. This time that came much more easily, not least because I was already thinking about Peacock in a wider context when I set to work.

Bassett Keeling was more of a challenge. James Stevens Curl recognised him as an interesting figure back in the 1970s and published several excellent articles on him. On the one hand, that meant that much of the groundwork had already been done. On the other, I was afraid of producing something derivative, and needed to go back to the sources to interpret them for myself. That some years ago, long before the idea for the book emerged, I had gone to look at all the drawings in the RIBA Collection of Keeling’s Roguish churches and chapels from the 1860s (some of the fruits of that session had previously emerged in the form of another blog post) was a good starting point and rattling the box made a few commissions that had either been overlooked or barely studied drop out. They won’t radically change our view of Keeling, but it was good to discover that there was still new material to be found.

The new discoveries include Keeling’s Wesleyan chapel of 1868 in Scartho on the southern outskirts of Grimsby, mentioned briefly by Curl, but not described and evidently not visited. It has even been overlooked by Historic England’s Designations team. Always a modest affair and considerably altered during its lifetime, it may well no longer be of listable quality. But as a characteristic work – still in places, at any rate – by an architect to whose buildings posterity has shown little kindness and the only surviving example of his possibly numerous small Methodist chapels, it merited discussion. I visited in July, too late for the book to be modified to include an illustration, so a photograph appears here instead. Then there is Marlborough Mansions on Victoria Street in Westminster, given its attribution by Simon Bradley when he was working on that volume of The Buildings of England. Its main interest is in demonstrating the architect that Keeling became when he returned to practice after a hiatus lasting for the whole of the 1870s, and its aesthetic distinction is limited. But as a largely unaltered, albeit not characteristic work, it deserves a mention, if only to show just how thoroughly he purged himself of Roguishness subsequently.

The chapter about Keeling has come out longer than the others, but that is because a study of his work necessitated confronting two issues that are fundamental to the very definition of Rogue Gothic. The Strand Music Hall was an important test case for critical responses to the style on two counts. Firstly, is the notion that there was a mainstream Gothic Revival and that Rogue Gothic stands apart from it something that was felt at the time? Or is this entirely a 20th century interpolation? Examining the furore it provoked sheds light on the matter. Secondly, this it is one of the rare instances where an exponent of Roguery explained in writing the aims and thinking behind his architecture. There was a great deal to say about both matters, and the structure of the book made it possible finally to examine them in a context that extends beyond an account of Keeling’s life and career. Then there is the matter of structural cast iron in Revived Gothic and whether, as numerous commentators have surmised, the very presence of an historically inauthentic material for the Middle Ages in a religious building is a defining feature of Roguery. This turned out to be very complex issue and perhaps no other passage in the book went through quite so many rewrites before I felt I had got a firm handle on what I wished to say. It was important to confront some lazy generalisations, but, for a while, the further I explored, the less sure I was of my ground. First the question of ‘who did it first’ had to be tackled, then ‘and in what form as to be relevant here’, had to be defined.

You’ll have to read the book to find out what conclusions I reached. I won’t summarise or repeat its content in this post. That would be unrealistic, and it would also be doing my publisher a profound disservice. Nor have I updated the existing blog posts with any of the material that has come to light since I started work on the book in earnest around September 2022. They have all been left more or less as they were when I first published them to record how much ground I have covered in the intervening period. If you want to read what are now the definitive accounts of the lives and works of my trio, then you’ll have to buy a copy of The Rogue Goths. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t figures and buildings in the book that would yield plenty of interesting material that could yet be explored on the blog, and this post is thus both a chance to tie up some loose ends and a starting point for further investigations.

Andrew Saint remarked after reviewing an early draft of the book that it was important not to overstate any of the claims that I make for Roumieu, Peacock and Keeling – that they are chosen as much for what they illustrate about a particular episode in Victorian architecture as for their intrinsic interest. Rogue Gothic is still a rather nebulous concept that can probably never be exhaustively defined (it is, after all, a retrospective interpretation, like so many terms in art history), but the book can at least tease out some common threads, identify some shared aims, diagnose and taxonomise. For that reason, the three biographical chapters are bookended by an introduction and a conclusion, in which I try to get to grips with the whole notion of Roguery and the Goths among its exponents. Beyond setting my trio in context, I could not hope to do the subject full justice, but it was important to show how they compare to their Roguish peers. I was able to bring in some old friends who have featured previously in this blog, all of whom are written up at greater length in the posts on their lives and work – Poundley and Walker, Edward Blackburne, Henry Darbishire, E.B. Lamb, Charles Buxton, John Croft and S.S. Teulon.

This chapter was perhaps the most fun to write, but also the most difficult. It was a chance to fly the flag for a number of minor masters who have intrigued me for a long time, who might have been the subject of blog posts had the book not materialised and may yet be. So far, Poulton and Woodman have come closest to that. The partnership of William Ford Poulton (1922-1900) and William Henry Woodman (1822-79), which lasted from 1853 to 1863, produced some wildly original buildings in which they played fast and loose with pretty much every style at which they tried their hand – principally Gothic, but also Italianate and Lombardic Romanesque. In 2021 I started putting together a works list, but the project got waylaid after I embarked on Teulon and then on the book, and they still await their due. They are illustrated (figuratively and literally) in the first chapter by their cemetery chapel of 1858 in Box, Wiltshire. That building type was a speciality of theirs, but they also designed some enormously varied and original nonconformist chapels (usually for the Congregationalists, Poulton’s own denomination), and then there is Wokingham town hall (1860), a major bit of civic Roguery.

I knew enough about Poulton and Woodman to be able to select what I thought were especially important works in their prolific output. With other architects, I was flying blind, since I knew them by only one or two buildings. Did I need to acknowledge the fact that I was making superficial judgments of figures who deserved a lengthy study, or did the fact that few other images of their work were in circulation point to the fact that they had done nothing else of comparable interest? In certain cases, there was no room for doubt. I initially thought St Luke’s in Blakenhall, Wolverhampton (1860-1) was not much more than a curiosity – a brave effort, but the kind of thing that other people had done better and in greater quantity. But it soon became evident that was a much more important building than I had first bargained for, and its architect, G.T. Robinson (1827-97) a far more interesting figure than I had ever imagined.

The Blakenhall church represents one of the earliest instances of the use of structural cast iron by a Rogue Goth for an Anglican place of worship, which is of particular interest given Robinson’s significance as a designer of some of the first big Victorian market halls with cast iron and glass structures over the trading floor – that of Bolton, completed in 1855, for one. St Luke’s is illustrated in the book with an evocative black and white image of the currently inaccessible interior, but this is a building that has to be depicted in colour. Thanks to a visit in early April and happy chance – on an otherwise grim day, the sun briefly came out and shone brightly around the time I arrived – so it now is. Robinson seems to have been capable of similarly vivid results with any style, as shown by his town hall at Burslem, which yields nothing to Roumieu’s equally original takes on Italianate. Evidently a multitalented man, he combined architecture with journalism and was nicknamed ‘Metz’ for his heroic attempts to file dispatches from that city for the Manchester Guardian while it was under siege during the Franco-Prussian war.

Of all the figures I touched upon, there is none whose work I’d like to delve into as much as that of James Medland Taylor (1834-1909). Though a native of Essex, he was most active in the northwest. When I was writing the introductory chapter, I knew of only two churches by him – St Anne’s in Haughton (1880-2) and St Agnes’s in Longsight (1884-5), both in suburban Manchester. They are such interesting and original pieces of architecture that I was soon investigating further and what I found turned out to be most rewarding. The superb Architects of Greater Manchester 1800-1940 site contains a good biographical outline and a works list, but there is clearly a huge amount to be done before we have an account of Taylor’s career that does it proper justice. He was briefly an assistant to S.S. Teulon, and although conventional wisdom has tended to the view that Teulon had no direct successors, detailing in works such as Christ Church, Blackpool (c. 1863) bears more than a passing resemblance to the older architects’ work. One would like to know a great deal more about what he absorbed from him, when and how.

Demolished as recently as 1982, Christ Church is now best known to us from a black and white photographic survey by the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments for England, which is indicative of the fate of several works by Taylor – lost quite conceivably because there was neither enough knowledge nor strength of feeling to put up a fight for them. The wholesale demolition and redevelopment of great swathes of Manchester in the 1960s did for some very interesting buildings, such as the tremendous St Luke’s, Miles Platting (1873-5). Though it was fire in 1961 that led to the demolition of the Audsley brothers’ St Margaret’s in Anfield (1873), Liverpool was similarly afflicted, and street-by-street clearance often had a profoundly detrimental effect even on buildings that were spared. Their Christ Church, Kensington (1870) has long been redundant as an Anglican parish church and is currently in poor condition. I am still not entirely sure how much of the output of William James Audsley (1833-1907) and George Ashdown Audsley (1838-1925) can truly be classified as Roguish – there is a real seriousness of purpose and much less whimsy than in the work of some of the architects featured here – but the quality, originality and force of these early works from the 1860s and 1870s come through so clearly that I was then and remain now prepared to make the case. It displays the bravado that constitutes one of the few common factors in a way of designing that is so multifarious as to resist generalisations. Ian Nairn, who got me interested in the Audleys’ work through his chapter on Liverpool in Nairn’s Towns, written in 1964, described Christ Church as ‘a tough, great-hearted building in a tough area’.

With Medland Taylor one only has to examine a few works to realise that this was no quirky minor master, but a mighty architectural imagination who maintained a high standard throughout his career. I feel more equivocal with some of the other Rogues still partly in the shadows. Charles Forster Hayward’s church-cum-chapel at Reach in Cambridgeshire (1860) and Duke of Cornwall Hotel in Plymouth (1863) are both grist to the mill where an overview of Roguery is concerned, but were they more than flashes in the pan? By chance, while the book was in production I came across an article on new architecture in Plymouth in the Building News of 18th August 1865 in which an anonymous critic speaks of the hotel in a manner that suggests that he for one certainly thought so. ‘There are such a number of good bits about this example of modern domestic Gothic that it is really a matter for wonder how they got into such a jumble. The architect who could design the large semi-octagonal dormer near the angle tower, and who could restrain his fancy and bridle his freedom to such admirable though severe detail as the ground-floor windows, ought certainly to have been able to have grouped his roofs and chimneys, and dormers and windows and turrets, effectively and artistically, without frightening sober-minded people by a luxuriance of picturesqueness and an extravagance of fancy unparalleled in Christian Europe’.

Yet these designs caused so much of a stir that enough architects seeking to reinvent themselves around that date were ready to jump on the bandwagon of Roguery. The mannerisms were not difficult to acquire and it was an easy style with which to attain piquancy. Whether the architects who did so had the skill, the imagination or the temperament to achieve sustained success with it is another matter. Who knows what further study of other figures whom I could record only in passing references will bring to light? Wykeham House, No 56 Banbury Road in Oxford (1865-6) and the Sir Tatton Sykes monument in Sledmere (1865) are buildings to reckon with, but did John Gibbs (1827-after 1874) always operate at the same level of inspiration? What did Rogers and Marsden do that stands comparison with their wonderful market hall in Louth of 1866-7? Where did G.E. Pritchett (1824-1912) show panache to equal or excel his church at High Wych (1861-2)?

No answers are possible for the time being, but I can at least include here images of buildings that either were not available when the book was being written or had to be omitted for reasons of space. Among them is St Mark’s, Dalston in Hackney (1864-6), whose architect, Chester Cheston Junior (1835-1907) could reasonably be described as a one-hit wonder, yet which is such an important reference point, especially where the use of structural cast iron is concerned, that it really should have been illustrated. That it was not is because it is (or at any rate was before a new lighting scheme was recently installed) a dark cave of a building, which came close to defeating my photographic skills. A professional shoot would have been needed, but the expense was difficult to justify. Horsley Towers in Surrey of c. 1855-60 is a problematic work. For spectacular originality it vies with the work of any of Rogues at their most flamboyant, but some superb ideas on the part of its amateur architect, the 1st Earl of Lovelace, badly needed nurturing and refining by a professional. They never got it, and the resulting crudeness is painful at times. Nevertheless, the gorgeous interior of the chapel encapsulates all that is most successful about this building and here it now is.

Economic stringencies and a lack of space also precluded illustrations of a number of intriguing works that are clearly in a Roguish vein, but sprang from the drawing boards of practitioners whose architectural temperament was usually anything but savage – as mentioned above, Goodhart-Rendel’s prerequisite for Roguishness. Capel Manor (1859-62) by T.H. Wyatt (1807-80), mentioned briefly, can now be illustrated here. The Roman Catholic church of Our Lady and St Augustine in Stamford, Lincolnshire by George Goldie (1828-87) of 1862-4 with its outlandish bell turret was missed out altogether, but can now find its way in, thanks to good weather on the same field trip in late July 2024 that took in Scartho and Louth.

I am all too conscious that the book is church-heavy in places. Given that both Peacock and Roumieu established their reputations as Rogues with the churches that they built in the 1860s, this was inevitable, but in a wider survey there would be work to do establishing a balance. Roguery is far easier to spot in ecclesiastical buildings, where there were clearly defined benchmarks of aesthetic propriety. It is harder to define in domestic and commercial buildings, where few such standards applied, there was no body such as the Ecclesiological Society to police them and much ultimately depended on the taste (or lack of concern therewith) of owners and developers. The Rogue Gothic that flourished in this sphere has been dubbed ‘demotic’ by J. Mordaunt Crook, which well conveys the relation of this vernacular to the ‘attic’ of G.E. Street, J.L. Pearson and their ilk.

As a splendidly invigorating exemplar of demotic Gothic, Rockmount, a villa in south London by Sextus Dyball (c. 1832-98), was an inexcusable omission from the book, which can now be rectified. I suspect mainly on the strength of Rockmount, Dyball has been mentioned in a piece by Jonathan Meades as an architect to look out for. At the moment, nothing is known that suggests he excelled himself anywhere else, and in this he perhaps is typical of the minor Rogues, whose originality and level of inspiration fluctuated depending on whether circumstances allowed them to rise to the occasion. For the same reason, one asks what J.S. Davis did that vies with Nos 31-51 Constitution Hill in Birmingham. The date of 1881-2 is already on the late side for something that incorporates a smattering of Ruskinian devices, but then the paradigmatic chronology established through works by mainstream architects sometimes is of little help where buildings such as this are concerned. House buyers and commercial tenants might initially have been suspicious of anything unfamiliar and developers wary of innovation that might consequently sell badly. On the other hand, once the public had developed a taste for Roguery, there was no reason not to carry on catering to it even when the avant-garde had moved on.

William Wilkinson, architect of much of the first phase of residential development of north Oxford, turned out to be rewarding to investigate. I did not know when I was writing the book th at at exactly the same time he began work there he was building a thoroughly outré commercial development in the City of London, Crosby House on Bishopsgate of 1860-1. It is not to be confused with Crosby Hall, the late Gothic merchant’s house still at that date extant on its original site, apparently almost directly opposite, though the name presumably was intended to create allure by association. The illustration, reproduced here, is taken from Thomas Harris’s Examples of the Architecture of the Victorian Age of 1862. It was praised by The Saturday Review (13th July 1861) as cogent proof of the suitability of Gothic for the modern city, the context being the battle between the Gothic and Classical parties in the competition for the design of the Foreign Office: ‘beauty and strict attention to architectural truth are hardly so remarkable as the convenience and the “light and airy” cheerfulness of the entire range of apartments’. Nothing is currently known of its later history, but it presumably had a short life before being demolished for redevelopment. It was at the frillier end of Roguery and Wilkin’s slightly later complex of houses and shops at Nos 23-24 Cornhill in Banbury has more punch.

Thomas Harris has long been on my radar as a figure who deserves proper investigation. To the best of my current knowledge, there is no survey of his life and work. I mention briefly his inclusion by Goodhart-Rendel in the original canon of Roguery of 1949, but the only work of which I was aware until recently that unequivocally qualified him for the soubriquet was an unexecuted design of 1860 for a terrace of shops and flats in Harrow. It was published in The Builder and has been much reproduced, but tends to be discussed out of context. Harris was one of several architects of the period troubled by the persistence of historicism in the age of the steam engine and electric telegraph. He deplored copyism and wished to see architecture that was an authentic expression of his time. He did not quite know what it would look like, but felt that even tentative, clumsy steps in this direction were preferable to continuing in the established vein. In 1860, he published a brief pamphlet entitled Victorian Architecture – A few words to show that a national architecture adapted to the wants of the nineteenth century is attainable. Unusually for a theorist of the period, he largely avoids questions of style, concentrating instead on what he saw as the proper treatment of different materials, with a few words on general principles of modelling and composition. The consensus among architectural historians seems to be that Harris’s project flopped – his attempts to embody his theory in practice came out looking little different to the work of his peers, it failed to be taken up widely and he quickly abandoned it. Milner Field in Bradford, the home of Titus Salt, of 1872 was an original bit of High Victorian Gothic, but perhaps not strongly personal, and by the time of Bedstone in Shropshire of 1884 he had gone Queen Anne.

Or so I thought, until I perused Examples of the Architecture of the Victorian Age, published two years after his pamphlet. It includes fine lithographs of two small, but very engaging works that Harris executed in the West End of London, one of which is reproduced here. We are lucky that they were included: tracing the history of lost buildings in a part of the capital that is always under intense pressure from developers can be difficult because their short lives often left little trace in the archives, and I have yet to find photographs of either. Attempts to track down illustrations of what Goodhart-Rendel describes as wholly characteristic works by Harris not far away on Wells Street and on the south side of Oxford Street next to James Wyatt’s Pantheon have so far been unsuccessful. Any information about these and any other buildings by him is, of course, gratefully received. Goodhart-Rendel viewed Harris with some disapprobation as having, for all the loftiness of his aims, simply arrived at Rogue Gothic by a roundabout route – ‘The novelty… was only skin deep, he had nothing new in construction to offer, but merely a fancy for queer shapes arbitrarily conceived’ – but his architecture is nonetheless highly distinctive stuff, even in the context of the 1860s. St Margaret’s House in Lowestoft gained an attribution to Harris when the Suffolk volume of The Buildings of England was revised. Judged against other works and the architect’s own principles of design, this seems plausible, but further investigation is needed.

Industrial buildings are also under-represented in The Rogue Goths. Other than a stables and depot for delivery vehicles on what became the Charing Cross Road, Roumieu’s buildings for Crosse and Blackwell are inadequately recorded and his enormous complex for Petty, Wood and Co on Southwark Bridge Road is not characteristic of his Roguery in full flow. Peacock designed three warehouses, but they are tame stuff compared to his churches of the 1860s. It is a problematic area. On the one hand, the High Victorian period is notable as the time when industrial buildings and infrastructure began to be regarded as worthy of really eye-catching architectural treatment. On the other, the building types concerned often owed so little to historical precedents that debates over whether the treatment of an existing architectural language are to be regarded as excessively wilful can become pointless. At the very least, it needs to be demonstrated that the architect in question was consistently Roguish, showing himself thus with building types where there is no room for latitude of interpretation.

But I would like to include one industrial structure by a figure who emerged during my research as an architect to look out for. Henry Jarvis (1816-1900) was surveyor to the parish of St Mary’s, Newington and later District Surveyor for Camberwell, designing some interesting and original town churches in those parts. In one of them – St John the Evangelist, Larcom Street in Walworth (1859-60) – for the first time he used cast iron columns in the manner that became one of the Rogues’ favourite mannerisms, i.e. matchstick-thin and supporting disproportionately chunky brick arches. At Nos 109-111 Farringdon Road in Clerkenwell, he deployed Venetian Gothic motifs for the warehouse of a chromolithographer called William Dickes, but used them as much like elements in a pattern as architecturally, leaving the viewer with a sense that they might easily be extended almost ad infinitum either laterally or vertically.

Were I to set out on another field trip to view examples of Roguery, I would aim for much further afield to investigate the parallels in French and American architecture. There is all of half a page on this subject, but in a book of this length I could do no more than show I was aware that they deserved further attention. To what extent these parallels are coincidental, or at any rate spring from the Zeitgeist rather than traceable direct routes of influence, is difficult to say. In the case of the Roguery of the East Coast of the United States, it seems reasonable to posit the latter. English architects, such as Frederick Clarke Withers (1828-1901), brother of Robert Jewell Withers, emigrated to live and work in America. So, later on, did the Audsley brothers. The Anglosphere would have facilitated the spread of influential publications, be they Ruskin’s writings on architecture or the trade press, and though the results might easily have ended up pale and derivative, yet American architects made the style their own with tremendous gusto and originality. I would have loved to include some illustrations of the examples discussed in the book, especially the work of William A. Potter (1842-1909), but even on Wikipedia Commons suitable photographs were difficult to find. The two illustrations here must stand for what I would have liked to be able to include. For colourfulness and wildness, this architecture vies with anything on this side of the Atlantic and, indeed, on this side of the Channel.

I have yet to find out anything about Jean-Antoine-Gabriel Davioud (1824-81) and the Lobrot brothers to convince me that Goodhart-Rendel was justified in drawing comparisons between exponents of ‘le style rageur’ and any of the English and Scottish Rogues (with the possible exceptional of Frederick Pilkington’s tenement buildings), but a chance discovery that the term was applied to Viollet-le-Duc’s tomb of the Duc de Morny in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris (1865-6) delighted me no end and seemed a very apt categorisation, so here it is. The thing looks like Gothic refracted through the same sort of lens through which Alexander Thomson viewed Hellenic antiquity, or else as Gustave Moreau might have imagined the architecture of the Middle Ages. I include here also an unexecuted design by Louis-Auguste Boileau (1812-96) for a new church of Saint-Denis in the Parisian suburb of La Chapelle of 1850-3, alluded to though not mentioned explicitly in the book. It perhaps needs to be approached with caution, since what appears to be unbridled outlandishness was in fact a demonstration of an esoteric, yet ultimately rationalist architectural theory, which puts it on a very different intellectual plane to the work of the Rogues, but it has at least some distant kinship with them for the shock effect of its aesthetic. At a push, one might say that Boileau shared the concern voiced explicitly by Thomas Harris, E.B. Lamb, Alexander Thomson (and acted on implicitly by other Rogues) about the need to wrest 19th century architecture from historicism and to work towards an authentically contemporary style. He certainly shared the interest of Keeling and others in the use of structural ironwork, in which he saw even greater potential.

I confidently predict that my book will draw numerous comments along the lines of ‘I’m surprised that you didn’t include [insert name of particular favourite]’. My answer to them will be that I never pretended to comprehensiveness – the length simply did not allow for it. There are entries in the index for all the figures mentioned above, but there are also plenty of candidates for inclusion who have come forth since the manuscript was delivered and who, I’m afraid, will have to wait their turn until a second, expanded edition becomes possible. These architects and their works are already so numerous that only a brief selection can be listed here. They include William Hayward Brakspear (1818-98), architect of the outlandish Dome Wesleyan church at Bowdon, Greater Manchester (1874-80, demolished 1968) and the forceful Briar’s Hay in Rainhill, St Helens (1868), a mansion for alkali and glass manufacturer John Crossley.

My book addresses the generalisation that Roguish places of worship were generally built for Low Church congregations, who cared little for aesthetic propriety and delighted in flouting the High Church party’s canons of aesthetic propriety. That a design like Briar’s Hay should have been devised for a client such as Crossley requires one to confront another old canard about Roguery – that domestic works in the manner were commissioned by Victorian nouveau riche industrialists, whose rapid ascent from humble beginnings meant they had had no time to be schooled in received good taste. As with churches, I suspect that it will turn out to be flimsy on closer examination, but this is a huge, complex topic and only a much longer study would allow for the discussion that it deserves. Another industrialist who commissioned a major piece of domestic Roguery was Alderman George Baker (1825-1910), a staunch Quaker and life-long admirer of Ruskin’s utopian ideals. In around 1871, he bought an estate in the Wyre Forest outside Bewdley, five years later giving 20 acres of it to Ruskin for the establishment of a community based on the principles of his Guild of St George (in the event, the first settlers did not appear until 1889). Baker himself took up residence there and commissioned architect William Doubleday (1846-1938) to design a mansion that went up in 1875-7 and was named Beaucastle on completion. Yet for all Baker’s enthusiasm for Ruskin’s teachings and yearning for an Arcadian England undefiled by the industrial age, this is a thoroughly 19th century building, unthinkable without the High Victorian revolution in taste – a fairy tale castle, but one that sprang from the most savage of Rogue Gothic imaginations.

Beaucastle exploits handsomely its hilltop site – alas, impossible to show here as there is no public access to this private property and thus no decent images of it on open sources. Another piece of domestic Roguery that makes equally successful use of a dramatic natural setting (this time earlier and for old money – it was commissioned by the Hay-Williams family of Bodelwyddan Castle) is Plas Rhianfa of 1849-50 in Llandegfan, perched on the Anglesey side of the Menai Strait. Its designer, Charles Reed (later Verelst, 1814-59) produced a strongly individual piece of architecture completely unlike the Puginian Gothic manors, Tudor Revival mansions or Baronial and Jacobethan piles that anyone in the market for a country house might have commissioned at the time. The house was supposedly inspired by the chateaux that Lady Sarah Hay-Williams had seen and sketched in the Loire valley, but it takes a skilled architect to turn a client’s fancies into a something buildable and usable. What came out of their collaboration, which at most only paraphrases the French Renaissance, suggests a major talent whose early death one can only rue.

Or what about the west garth of Blackfriars in Norwich, remodelled in 1861 by James S. Benest (1826-96) to serve as the New Commercial School? Benest was city surveyor and not immediately a name to conjure with, and in any case this work tends to be overlooked because of the exceptional interest of the host building – the only more or less complete religious house of any of the mendicant orders to survive from medieval England. But as a paragon of Rogue Gothic it would be difficult to beat. It is not simply the assemblage of classic signature traits, such as striped arches and red sandstone column shafts, that impresses, but the sheer perversity of features such as the chimney stacks emerging from gables above large windows, the pointed arch dormers breaking through the roofline, and the exceptionally tall and narrow windows to the return elevation of the lower volume that extends out to the streetline.

For another example of Roguery in the service of a civic function, making a display where one might not necessarily have expected it, take the Royal Albert Homes on Hills Road in Cambridge by Frederick Peck (1828-75). The earliest range, pictured in the header, is of 1859 (it was subsequently enlarged in several phases in the 1870s and 1880s, though the later additions are stylistically indistinguishable). As with the Norwich Commercial School, the entrance front encapsulates all the typical features of Rogue Gothic – a liking for Picturesque irregularity which stems ultimately from architecture of a good 40 years previously (that endearingly overscaled pyramidal spire on a really deep corbel table), scattered features drawn from the Ruskinian avant-garde of the period (plenty of constructional polychromy, although combined with walling of plain white Suffolks) and structural redundancy (the buttress that serves no useful function beyond leading the eye up to the clock face). It is very much in the same vein as the almost exactly contemporary and engagingly cranky lodge and chapel at Maidstone Cemetery that Peck designed with his then-partner E.W. Stephens – both tiny, yet full of entertaining detail.

A blog is, by nature, interactive, and candidates for inclusion in the canon of roguery are welcome, as is any information that answers lines of enquiry which I was unable to pursue further when writing the book or which are flagged up here. If my work inspires further research and discussion, then it will have served its purpose. There is a great deal of ground to be broken, and this is merely the start. It remains only to thank once again the people who made possible its publication: Andrew Saint, to whose generous spirit and encouragement it owes its very being; Alison Welsby at Liverpool University Press, who was more indulgent of and cooperative with my two book proposals than I had any right to expect, and her colleague Catherine Dutton; Sarah Davison at Carnegie for steering the book through production; Robin Forster for his magnificent photographs of surviving buildings by Roumieu and Peacock, and his perfectionism in doing the subjects justice; the Marc Fitch Fund and Alan Baxter Associates for their generous support that made such handsome illustrations possible; the Victorian Society for initiating the series of which this book forms a part and, in particular, Marie Clements for doing so much to promote it; and, finally, Historic England, under whose aegis it appears, and who put at my disposal the incomparable resource that is their photographic library. A special thank you is due to Katie Hawks, who picked me up by the scruff of the neck back in August 2020, not long after the first book proposal was written, and would not let me go until I had set up this blog. This book would have taken a very different, much poorer form without her. This author and the cause of Roguery are deeply indebted to you all.

Dear Edmund

Very pleased to hear from you again and excited about the book, now ordered from your publishers; a second enlarged edition sounds as if it’s a distinct possibility given the amount of additional material you refer to above but I’ll take a chance on the present work!

Best wishes

Chris Palmer

LikeLike

Many thanks for that and I hope you enjoy it!

LikeLike

Looking forward to the book, hoping it’ll be in my Christmas stocking (so probably buying it in January…).

LikeLike

Hope Father Christmas gets the hint and I hope you enjoy it when it comes!

LikeLiked by 1 person